Last updated: July 30, 2023

This is a post I need to write while it’s still winter. The Anishinaabeg, like most Algonquian and many other Native peoples, have a traditional prohibition on telling traditional sacred stories (aadizookaanag) during the warmer months. During the warmer months, unwholesome creatures—frogs, toads, serpents, and their kin—are active and may be listening, as are all the manitous (gods/spirits) and other characters mentioned in the stories. One of these characters in particular must never be named until winter, for to name him is to risk drawing his attention. And you do not wish to draw his attention. His domain is that of the waters, so it is only in winter, when the lakes and rivers are frozen over with ice and he is trapped slumbering in his domain, that the stories can be told.[1]

The Great Lynx

Were there not creatures inhabiting the deep waters more deadly and dangerous than any of the fish species? How should they be named? . . . How does one name one’s deepest, unspoken fears?

—Dewdney, The Sacred Scrolls of the Southern Ojibway, pg. 125

Misshepeshu, the water man, the monster . . . . He’s a devil, that one. . . . Our mothers warn us that we’ll think he’s handsome, for he appears with green eyes, copper skin, a mouth tender as a child’s. But if you fall into his arms, he sprouts horns, fangs, claws, fins. His feet are joined as one and his skin, brass scales, rings to the touch. You’re fascinated, cannot move. He casts a shell necklace at your feet, weeps gleaming chips that harden into mica on your breasts. He holds you under. Then he takes the body of a lion, a fat brown worm, or a familiar man. He’s made of gold. He’s made of beach moss. He’s a thing of dry foam, a thing of death by drowning, the death a Chippewa cannot survive.

—Erdrich, Tracks, pg. 11

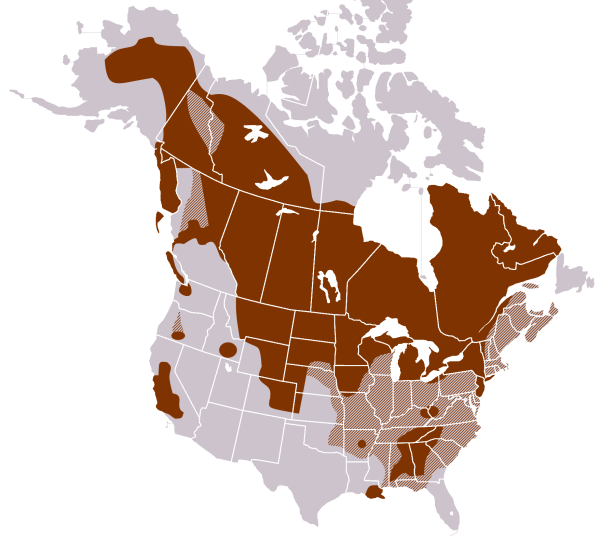

The character in question is the manitou of the waters and the underworld, Mishibizhiw or Mishibizhii, whose name literally means “Great Lynx,” but is often referred to as the “Underwater Panther,” “Underwater Lion,” and similar variants, and whose Ojibwe name has been spelled in dozens of different ways, most often as something like “Mishipeshu” or “Mishepishu.”[2] Mishibizhiw was originally distinguished from another manitou, the giant horned serpent Mishiginebig “Great Serpent,” but at least in many cases the two have since merged in Anishinaabe conception, with the name Mishibizhiw coming to cover the aspects of both (or mishiginebig, pl. mishiginebigoog, being the name of some of his underlings), and in this post I will treat both under the rubric of Mishibizhiw. In any event, as a result of this merger, there are basically two forms in which he is conceived. One is as his name would suggest, a large feline creature with an exceptionally long serpentine tail and horns, usually those of a bison; and he often has other chimera-esque features, such as spines along his back, fins, copper scales, etc., and is frequently described as white, or otherwise somehow visually exceptional or stunning (e.g., Waasaagoneshkang in Jones [1917:94, 96] doesn’t describe his physical form at all except to say waabishkizi “he is white” and geget sa onizhishiwan “he was truly beautiful,” while Eshkwegaabaw and Debi-Giizhig in Josselin de Jong [1913:14] say: Geget sa . . . bishigendaagozi, gooning izhinaagozi “He was truly magnificent; he looked like snow”).

This is true of the most well-known depiction of Mishibizhiw, the “most famous rock art painting in Canada” (Conway 2010:36), done in red ocher on the massive cliff face of Agawa Rock in Lake Superior Provincial Park on the northeastern shore of Lake Superior:

The precise age of the painting is uncertain, but there is some evidence that the Mizhibizhiw panel—there are approximately 17 panels at the site, containing 117 distinct images in total—was done in 1849.[3] Mishibizhiw is accompanied by two serpents, identified by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft as mishiginebigoog, while a canoe filled with people stands off to the side; most rock pictographs of Mishibizhiw somewhat ominously include a painting of one or more canoes. Note that he has a feline body, lynx’s cheek tufts, and bison’s horns, and a row of spines down his back. His tail in this image, as with other pictographs of him, is not as long as in images on other media, but otherwise it’s fairly representative. The image is justly famous. Mishibizhiw, “extraordinarily large compared with the usual rock painting” (Dewdney 1975:129), is a haunting, faceless, mesmerizing presence.

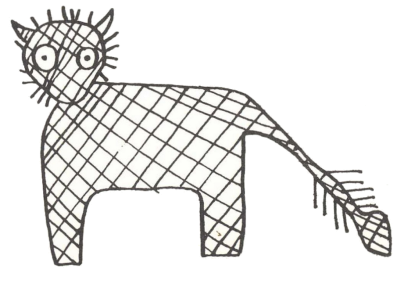

In almost all representations of him, Mishibizhiw is facing the viewer head-on as on Agawa Rock. To take another example (this time showing him with the more usual long serpentine tail, as well as with facial features), the following drawing is provided in John Tanner’s 1830 narrative of his life among the Odawas and Ojibwes, taken from a birchbark scroll featuring a curing song:

Beyond rock art and other highly “religious” contexts like healing scrolls and amulets, Mishibizhiw in his feline form was also fairly regularly represented on bandolier bags, pouches, sometimes clothing, and other daily items:

Aside from the feline form, the other form of Mishibizhiw, derived originally from Mishiginebig, is of a gigantic serpent, again with a bison’s horns on his head and a powerful tail, and again, sometimes fins or short legs, copper scales, etc. According to Smith (2012:97-99), for the Odawas and Ojibwes of Manitoulin Island, ON the serpent version is now the only one in which they visualize Mishibizhiw in terms of his actual physical form, though some of them continue to depict him in the feline form in works of art.

At least one Midewiwin birchbark scroll may represent the two forms at once. The Midewiwin was a society of curer-“shamans,” which had a minimum of four “degrees” or stages of increasing knowledge and power to which members could ascend. After they completed their training, the candidate for each new degree was blocked by hostile manitous guarding the entrance to the midewigaan (Midewiwin lodge) through which they had to pass to successfully progress, with the manitous for each successive degree being more powerful and dangerous, and those of the fourth degree incredibly so. In the image below from a ritual scroll depicting the candidate’s task in successfully passing into the fourth degree midewigaan, Mishibizhiw in his two forms, panther and serpent (or Mishibizhiw and Mishiginebig), appear linked together guarding the entrances:

It is significant that Mishibizhiw, in whatever form, is always envisioned and depicted as having horns. In Anishinaabe iconography, horns are a symbol of tremendous spiritual power, and are a conventional way of indicating a powerful medicine man, for example, as in the images below. As we’ll see later, a “Horned Serpent” figure was an extremely widespread belief across North America; still, Mishibizhiw’s representation as horned is a sign of his overwhelming power and majesty—he is the only manitou consistently depicted as having horns.

Additionally, Mishibizhiw’s horns are normally said to be made of copper, a fairly common mineral in the Great Lakes region, frequently found here as native copper, very unusually for copper deposit sites around the world, and which is considered both sacred and spiritually powerful medicine by the Anishinaabeg. In fact, copper is believed to have been deposited by Mishibizhiw, or to actually be his scales or pieces of him. The Jesuit missionary Claude Allouez, writing around 1665, observed that the Anishinaabeg “say . . . that the little nuggets of copper which they find at the bottom of the water . . . are the riches of the gods who dwell in the depths of the earth” and that “[o]ne often finds at the bottom of the water pieces of pure copper . . . . [T]hey keep them . . . as presents which the gods dwelling beneath the water have given them, and on which their welfare is to depend. For this reason they preserve these pieces of copper . . . among their most precious possessions. Some . . . have had them in their families from time immemorial.”[4] The connection between copper and Mishibizhiw is illustrated in some common stories. In one widespread one (told, among others, to William Jones by John Pinesi (Gaagige-Binesi) of Fort William, ON in the early 1900s, to Paul Radin by an anonymous consultant from near Sarnia, ON in 1912-1916, and to Robert Ritzenthaler by Pete Martin at Lac Courte Oreilles, WI in 1942 [Jones 1919:258-259; Radin 1924:513-514; Barnouw 1977:132-133]), Mishibizhiw appears in a whirlpool attempting to drown some girls in a boat; one of the girls strikes his tail with her paddle and a piece of his tail falls off as a chunk of copper (erroneously translated by Radin as “brass”), which provides the people with great power and good luck in the future.

Mishibizhiw is also envisioned as the guardian of copper, at least in some instances; while people could make use of copper they found if they treated it and Mishibizhiw with proper respect and gratitude, “stealing” copper without his assent was not tolerated, as in a story, first written down by Claude Dablon in the Jesuit Relations (JR 54:152-159), about four men who attempted to take a large amount of copper from Michipicoten Island but all ended up dead.

The German traveler Johann Georg Kohl, who visited the Lake Superior Ojibwes in 1855, also noted their veneration of copper. He relates a story told to him by an ex-fur trader, who described how in 1827 he attempted to obtain a large chunk of copper from the chief of one Ojibwe band, with whom he had good relations and who had in the past offered one of his daughters as a marriage match. When the trader made his request, the chief was reportedly silent for a while before responding:

Thou askest much from me, far more than if thou hadst demanded one of my daughters. The lump of copper in the forest is a great treasure for me. It was so to my father and grandfather. It is our hope and our protection. Through it I have caught many beavers, killed many bears. Through its magic assistance I have been victorious in all my battles, and with it I have killed many foes. Through it, too, I have always remained healthy, and reached that great age in which thou now findest me.

The chief eventually relented in return for a large payment of goods—which he subsequently offered as a sacrifice to Mishibizhiw—but insisted that the trader not reveal their transaction to anyone (obviously . . . not a request the trader honored . . .), and is described as “trembling and quivering” while the trader actually picked up the lump of copper. He eventually “bitterly repented” the deal “and ascribed many pieces of misfortune to it” (Kohl 1985:61-64).

As god of the waters, Mishibizhiw controls access to all the fish and other creatures within them—as well as, particularly in the creation myth cycle, land game as well—and can withhold them from humans at his whim. He is also responsible for the dangerous aspects of Lake Superior and other bodies of water in the region: sudden squalls, rapids, unseen currents, whirlpools which he creates through the lashing of his long tail, which is sometimes pictured as having a “heavy knob at the end” (Dewdney 1975:124) that can overturn boats. Many have drowned as a result of his activities. (“Appropriately” enough, several visitors to Agawa Rock have been washed off the slippery, narrow viewing ledge under the cliff by unpredictable rough waves and been injured or killed.) While he sometimes tolerates human presence, ultimately humans are creatures of the earth, and are not meant to cross the limits of their world and stay long on the waters, especially the large lakes. To do so is to trespass into Mishibizhiw’s world. Adding to the level of unease, Mishibizhiw is rarely actually seen in person. He may be seen in dreams and visions (JR 50:288-289), and his effects may be seen in rapids and whirlpools, but it is very rare to catch a glimpse of the manitou himself. You are more likely to simply be pulled into the depths by an unseen paw or tail, to drown, perhaps never to be found, as many drowning victims are never found—or perhaps to be found much later with your mouth, eyes, and ears stuffed with mud (Skinner 1923:47-48 quoted in Howard 1960:217).

Tobacco is a sacred substance for the Anishinaabeg, as it is for many Indian peoples, and is offered to various manitous in thanksgiving, in supplication, or simply as a sign of respect and devotion. Traditionally, Anishinaabeg present a tobacco offering before venturing onto the water, respectfully asking Mishibizhiw to forgive their temporary incursion into his world, take no reprisals against them, and keep the waters calm. They may also offer tobacco or food for him to ensure the supply of fish remains bountiful. In the past, Anishinaabeg would also occasionally sacrifice dogs to Mishibizhiw. Allouez, for instance, described how “[d]uring storms and tempests, they sacrifice a dog, throwing it into the lake. ‘That is to appease thee,’ they say to the latter; ‘keep quiet.’ At perilous places in the Rivers, they propitiate the eddies and rapids by offering them presents . . .”[5] He later directly mentions Mishibizhiw by name, saying, “They hold in very special veneration a certain fabulous creature . . . which they call Missibizi, acknowledging it to be a great spirit, and offering it sacrifices in order to obtain good sturgeon-fishing.”[6]

While dogs are no longer sacrificed, the practice of providing Mishibizhiw with tobacco offerings has continued to the present day for some people. For example, Niiskiigwan of White Earth, MN told Frances Densmore (1979:81) of an instance in which he was traveling with a group of Ojibwes by canoe when they reached a stretch of impassably rough water; Niiskiigwan offered “the Spirit of the Water” some whiskey and tobacco, and within “half an hour the wind veered and they were able to proceed on their way.” Chamberlain (1890:153) reports that when Euro-Canadians began constructing a bridge over part of Lake Simcoe, ON, a consultant of his, Niibinaanakwad, “sacrificed tobacco to appease the lion (mīshībīshī) which the Mississaguas [Mississaugas, an Ojibwe subgroup] believed lived there.” And Hilger’s (1992:62) consultants from the 1930s and 40s gave comments such as, “My aunt always strews tobacco on the water . . . before leaving the shore in order to drive away the evil spirits.” Although Smith (2012:120) reported that her consultants on Manitoulin Island no longer made offerings to Mishibizhiw in the late 1980s-early 1990s, a documentary short film by Francis (2018) shows some Manitoulin residents offering cornmeal to the manitou of a lake, so the practice is clearly still found there as well.

Failure to give proper offerings or show proper respect can have dangerous consequences. Marlene Stately (Anangookwe), an elder from Leech Lake, MN, describes how one day her grandmother forgot to leave a food offering for the water manitous, and they were caught in a whirlpool and barely escaped (GLIFWC 2013:169-171). Barnouw (1977:111-112) relates a story told to him by “Tom Badger” (a pseudonym) at Lac du Flambeau, WI in 1944, in which two girls are crossing Leech Lake in a boat when a giant leech appears in “a current . . . going just like rapids”; one of the girls quickly takes off her beads and other ornaments and throws them into the water as an offering, but the other girl “didn’t know that she should do this,” and is dragged to the bottom by the leech and drowns.[7] And one of Hilger’s consultants from Mille Lacs, MN commented, “Some white men drowned here in the lake, and that did not happen for nothing. Some things are sacred to Indians and white people who make fun of it can expect to be punished. Whites have laughed at Indians putting tobacco in the lake. We put tobacco into the lake whenever we go swimming, or when we want to cross the lake” (Hilger 1992:62).

One may cross into Mishibizhiw’s world not just by entering the water, but simply by being too close to the water. There is a very common story in which an infant is carelessly left alone near the shore for a brief period by a parent, who returns to find the child vanished. Usually someone in the village then hears the child crying underground, and the people try to track down the child, and sometimes even to kill Mishibizhiw. They reach Mishibizhiw’s lair, and sometimes do succeed in killing the manitou, but even when they “succeed,” they have usually come too late and the child has already been killed. Such stories can be found for example in Blackbird (1887:82-84), Radin (1924:493-494, 525-526), Skinner (1928:169-170), Jones (1919:258-261), Morrisseau (1965, cited in Smith 2012:134-135), King and Rogers (1988:74-75), GLIFWC (2013:126-129), and a somewhat different version in Webkamigad (2015:98-109).[8] While the normal version involves a stolen baby, in at least one story (Radin 1914:81-83) Mishibizhiw kills an adult woman walking beside a river.

Although the entirety of the water and underworld realm is Mishibizhiw’s domain, and he can appear anywhere at any time, there are particular sites which are much more intimately linked with him than others. Certain lakes with unusual features are said to be signs of his presence: a lack of fish, oddly colored water, a sudden drop-off in the lake floor or a deep hole or chasm—all these are dangerous signs that Mishibizhiw makes his home here, and these places are usually avoided. Such areas include a deep underwater cavern that gave Manitoulin Island (Old Odawa *Manidoowaaling “The Manitou’s Den”) its name.

Smith claims that in addition to the “Den,” there are a couple of “bad lakes” on Manitoulin as well, Whitefish Lake and Quanja Lake. She describes her visit to Quanja Lake, which she found both “striking and disturbing” (Smith 2012:114):

On our side . . . the lake was extremely shallow, just one to two feet, and banked by a sandy beach. The far shore was ringed by forested cliffs, and on that side the water was a very deep green-blue. The drop-off from shallow to deep water was so extreme that it appeared as if a line were drawn straight down the middle of the lake between the light shallows and the dark depths. What the lake recalled more than anything was a water-filled crack or ravine which had overflowed its banks on our side.[9]

A similar “bad lake” associated with Mishibizhiw, located several miles inland from Lake Nipigon, was described by the missionary Frederick Frost, who refers to it as “the mysterious lake” (Frost 1904:130-136). He states that “[t]he Indians go to it in winter, but never in summer . . . . They would not think of embarking in a canoe upon its surface for any consideration” and notes that there are other lakes they avoid in summer as well, because these “are, they believe, inhabited by fishes of enormous size and vicious habits, something like the sea serpent, that destroy any canoe and eat up any poor Indian who happens to come near.” Frost and a brave Ojibwe companion set out to explore the lake. When they arrived, Frost found that:

It was truly a wonderful sight [i.e., a sight inspiring wonder and amazement]; the water was, indeed, a peculiar color, a glittering, lustrous, greenish blue, not like the color of the water at Bermuda, or the blue of the Mediterranean, nor like the water in the harbor at Barbadoes, nor a mixture of these. The Indian was right when he said it was ghastly. It was a beautiful color, yet somewhat repulsive. I have never seen a blue snake, but it was the same color a snake would be, supposing it were blue. It was intensely brilliant, glittering in the sunshine; it looked like a pigment . . . . I do not wonder that they were struck with the unusual appearance of the lake. It was not sunshine that made it that peculiar color; it was not the reflection of the sky. It was the same when cloudy; it was the same always, in the daytime, probably.

Until now I’ve spoken of Mishibizhiw as an individual, but this is not strictly accurate. There are many such beings, though they have an ogimaa or chief. “Mishibizhiw” as a term is thus vague, and can refer to the individual, chief Great Lynx, or to the class of Great Lynxes of which he is chief, or to some specific non-chief Great Lynx. This multiplicity of Mishibizhiwag explains, in part, how he can be intimately linked to so many specific places, as well as how he can be killed—as in some of the “lost child” narratives mentioned above, and in other narratives that will be described below—yet still survive. However, I will continue to speak of “Mishibizhiw” in the singular, for the most part.

As noted, Mishibizhiw is god not just of the waters but of the land underneath the earth. This is another part of the explanation behind his ability to appear in so many places: he moves between different bodies of water through hidden underground passageways, to emerge when one least expects him. Where he comes close to the surface, or travels across the surface, bogs, spongy ground, and quicksand are created. James Simon of Manitoulin told Smith (2012:100), “Sometimes when the land goes soft on you, he’s been there.”

Just as humans were not meant to spend too much time on the water, we are not meant to traverse this other boundary of our world by traveling under the earth. There are stories in which people foolishly do so, and wind up suffering negative consequences. In one tale from William Jones’s collection, by Gaagige-Binesi, one village of people is having trouble catching enough fish in a large lake, so they dig an underground passageway (zhiibaayaag) connecting the lake to a smaller manmade pond, with their chief undertaking the task of funneling the fish into the smaller artificial pond, while the people will close off the passageway once he has done so. But their action—not merely digging underground but making an underground passage that connects bodies of water—is exactly what Mishibizhiw does, and what humans should not do, and the villagers, with the exception of their chief, are annihilated by Thunderers (see discussion below), though the chief is eventually able to restore them to life (Jones 1919:240-245).

Humans interact with manitous in several ways, depending on the situation, but primarily the relationship between manitou and human is one of respect and dependence on the part of the human and consequent benevolence and pity on the part of the manitou.[10] This is reflected in the customary address of a manitou as “Grandfather” or “Grandmother.” As long as a person behaves respectfully and follows the proper ceremonies, a manitou will indeed take pity on them and their relationship mirrors that between a grandparent and grandchild, with the manitou guiding and providing to the person support and blessings of power or a good long life. These are deeply personal relationships—especially those with one’s tutelary/guardian manitou (called a bawaagan in some dialects) acquired during the childhood vision quest—despite the usually enormous gap in power between the person and manitou.

This is not the case of all human-manitou relationships, however. For instance, the only relationship humans had with windigos, the anthropophagous ice monsters, was one of abject terror. Likewise, although people show Mishibizhiw great respect in recognition of his power and rights, and ask for his protection, the Mishibizhiw-human relationship is not one of pity and dependence respectively, but one in which the best humans can usually hope and ask for is forgiveness and benign neglect.

Nonetheless, in exceptional cases, some people have formed personal relationships of sorts with Mishibizhiw. These could take three main forms. In one form, Mishibizhiw showed up during someone’s vision quest fast and offered himself as their bawaagan; the proper response in such a dangerous situation was to reject the vision and try the quest again. The youth might also have their tongue scraped with a cedar knife to help render the bad vision impotent. (The vision quest was never held during the summer, at least in part to lessen the likelihood that Mishibizhiw or a similar manitou would appear. Likewise, the location where the quest-taker spent their fast was often in a platform in the trees or some other raised location [see, e.g., Densmore 1910:119; Kohl 1985:235-237]—as far from the ground, and thus the influences of the underworld/underwater realm, as possible.) But in some cases a person willingly accepted the vision,[11] and in other cases a person failed to recognize that they were speaking with Mishibizhiw until it was too late.

Dahlstrom (2003) presents a story of just such a situation for a Meskwaki boy. (The Meskwakis or Foxes are another Algonquian people, like the Anishinaabeg; the story was written by Alfred Kiyana, a native Meskwaki speaker, around 1912.) In this case the boy is not on a traditional fasting vision quest, but swimming in the icy water during winter as a substitute for fasting, when he suddenly winds up in a lodge with four manitous, who tell him, “Now, grandchild, we certainly bless you.” Other than the fact that this takes place in the water, so far this may seem like a normal, propitious vision—the manitous offer to bless the boy and address him as a grandchild. However, the manitous immediately reveal that “they” have been deceptive: “‘But we are not really four now,’ they told him. ‘I am just one,’ he said.” The now visibly singular manitou then explains that the young man should return in the summer, and he will provide him with the actual blessing then. Despite the warning signs—the young man had no tobacco, he met the manitou underwater, the manitou was acting alone rather than appearing with other manitous, he had initially been deceptive, and the blessing must take place in summer and not winter—the young man agrees. The manitou does give him a blessing that summer, which the youth uses to successfully kill many Sioux. Immediately after receiving the blessing, however, another, winged manitou arrives and scolds the boy for accepting the blessing from the underwater manitou instead of from the winged manitou, whose blessing would have been far superior. Much later, the underwater manitou kills the youth’s parents, and is about to kill the youth himself when the winged manitou intervenes to save him.

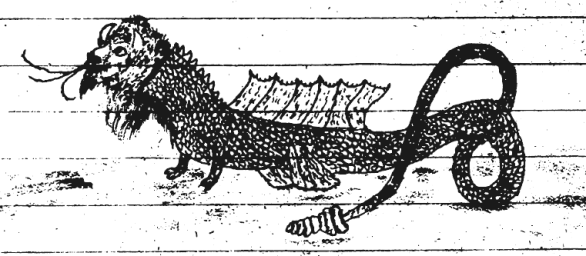

Kiyana included in his manuscript of the story an illustration of the underwater manitou (of whom the boy says “wîna-nîhka kîshâkochi-meko-neshiwinâkosikwêni” “he must really look extremely terrifying!”), which shows him as a chimera, somewhat similar to Mishibizhiw, with a bison’s head and horns, fins, two legs, a reptilian/serpentine body, scales, and rattlesnake’s tail:

A second type of relationship humans could have with Mishibizhiw, or at least indirectly with some of his serpent underlings, was a sexual or potentially sexual one. Pomedli (2014:181-183) relays several stories from Rama, ON, collected by G. E. Laidlaw, in which women take a serpent for a husband or as a close friend. In most cases, a male relative kills the serpent. In one of the stories, a 12-year-old girl befriends a serpent, but her father shoots it; she complains, “Why did you kill the best friend that I had?” and dies several days later from grief. In a story from Laidlaw (1927:68), told by Lottie Marsden, a young woman disappears from her family for several years, and returns with a serpent daughter, having married a serpent in her absence. Her father secretly murders both her husband and the child, but tells his daughter that the husband was killed by Mohawks, which the daughter believes (and also believes the child’s death to be an accident). In a Plains Ojibwe story (Skinner 1928:169), an unknown man comes and sleeps with a Sioux woman for several nights; there’s no indication that she knows who he is, but the narrator states that another “girl saw him; he was a horned snake.” She becomes pregnant, and while her husband at first assumes the child is his, the woman eventually gives “birth” to a hundred eggs. Unlike in most other versions, here the husband does not murder the snake, his wife, or the offspring—instead he places the eggs by a lake, following instructions received in a dream. Since the protagonists are Sioux, it’s likely that the story was taken by the Plains Ojibwes from the Sioux and is not originally an Ojibwe one; it is evidently found among other Plains peoples as well, such as the Blackfeet (see here for example), and I suspect is a more broadly distributed Plains tale.

The most widespread version of this theme is the “Rolling Head” story, which is very common among Algonquian and neighboring peoples. Though the details vary somewhat, in general the story begins with a family with two children, in which the husband learns his wife is being neglectful of her duties and is always dressed up when he returns home from hunting. Hiding himself, he discovers she is having an affair; he then proceeds to kill the wife and sometimes the lover. (The story then continues with the wife’s severed head, or reanimated body, chasing the children, who have to throw magical objects behind them to obstruct her, usually followed by further episodes which need not concern us.) In most instances, the wife’s lover is a serpent, usually one living in a hole in a tree, and often multiple serpents; though in the traditions of some other cultures, and occasionally in Anishinaabe versions, the lover is a bear instead. The lover is a serpent in a tree in the version collected by Ray and Stevens (1971:48ff) and both versions of the story in Jones’s collection—the first told by Marie Syrette of Fort William, ON (Jones 1919:44ff), and the second by Waasaagoneshkang of northern Minnesota (Jones 1919:404ff). Laidlaw (1915:74-75) also relays a version of the story from Peter York of Rama in which the lover is described in the text itself as a “man,” but where the preface reads: “The story of a woman who visited a man who lived in a tree, and who could change himself into a serpent when he wished.” Most interesting of all, in a Cheyenne Rolling Head story given by Leman (1996), the lover is explicitly named as a méhne, the Cheyenne equivalent of Mishibizhiw! In addition, Kroeber (1900:184-186) gives a different Cheyenne version which omits the actual Rolling Head episode which follows the adultery, and in which the lover is “a large snake” that lives in a lake; since the story was told to him in English and not Cheyenne, the term méhne is not used, but that’s clearly what’s involved.[12]

These stories are part of the larger class of Anishinaabe stories in which a young man or more often young woman marries or cavorts with an animal, normally with negative consequences, though the relative consistency in the woman-serpent stories of a male relative murdering the serpent lover, the wife, and/or any children of their union is noteworthy, as is the attribution of malevolence to the serpent and/or woman. More often, in other “animal spouse” stories, the human is simply “foolish” or the animal is somewhat deceptive or acting improperly in some way, but is not portrayed as actively malevolent.

The final case in which someone can form a personal relationship with Mishibizhiw is when a person, usually only a very powerful sorcerer (and usually an evil one), actually seeks such a relationship out. Mishibizhiw’s power is tremendous, and he can provide enormously powerful medicine to those strong and brave and talented enough to acquire and wield it. Sometimes Mishibizhiw will indeed agree to provide the person with some of his power. Yet their relationship in such cases usually remains very different from the normal relationship between a beneficent manitou and a human; this is a Faustian bargain. Mishibizhiw’s power “is given neither freely nor with any affection, not in the way a grandfather would give it” (Smith 2012:121).

In one story, relayed by Kohl (1985:422-425), a man dreams of Mishibizhiw over several nights, and eventually gives in to the temptation and approaches the water where he is instructed to summon the manitou by drumming on the water with a stick. A massive whirlpool appeares, sucking in everything around it while the water level of the lake rises and nearly drowns the man, then eventually recedes, and at last “the water king emerged from the placid lake, in the form of a mighty serpent. ‘What wilt thou of me?’ he said. ‘Give me the recipe,’ he replied, ‘which will make me healthy, rich, and prosperous.’” Mishibizhiw tells the man to take a substance from off of his horns, which will serve as powerful medicine. In this story the substance is vermilion, but normally it is copper, which as we’ve seen Mishibizhiw’s horns are usually said to be made of. The manitou then consecrates the vermilion and instructs the man in how to use it. Then he adds the dagger thrust, warning the man that “one of thy children must be mine in return for it.” “‘Every time that thou mayst need me,’ he then added, ‘come hither again. I shall always be here. Thou wilt have, so long as thou art in union with me, so much power as I have myself. But forget not that, each time thou comest, one of thy children becomes mine!’” The man returns home, and finds his wife is already dead. He greedily uses the power gained from Mishibizhiw to become “a successful hunter, a much-feared warrior, and a terrible magician,” while his children die one by one. The story ends with the note that “at length a melancholy fate befel him, and he ended his days in a very wretched manner,” though the details are not specified.[13]

(This practice has continued to the present—people interested in “bad medicine” still go to lakes where Mishibizhiw is thought to live in order to collect it [Smith 2012:114].)

This brings us to Mishibizhiw’s role in the Midewiwin. As was noted, the Midewiwin consisted of multiple degrees—usually eight, but only four primariy degrees; very few people progressed past the third degree, and almost none past the fourth degree, beyond which further advancement was generally seen as unnecessary—with candidates for each new degree undergoing a long apprenticeship with an experienced mide (Midewiwin member, sometimes inaccurately referred to as a “priest”) to learn herbal and other medicinal cures, proper protocol for their initiation into that degree, and Midewiwin lore, songs, and rites. Once they were ready, the candidate was admitted to the given degree in a special annual or semi-annual ceremony. However, each increasing degree, since it would confer on the initiate increased—and, in the wrong hands, potentially deadly—power, was guarded by dangerous manitous who had to be “conquered” to advance. As we’ve seen, in Midewiwin scrolls the entrances to the higher degree lodges are illustrated as being blocked by horned serpentine manitous or images of Mishibizhiw in his feline form. In the fourth degree in particular, the candidate was blocked by Mishibizhiw or his emissaries, breathing fire and pestilence across the entrances to the midewigaan lodge, which they would have to dispel, with the encouragement of their mide teacher and other officiating mideg (Dewdney 1975:110, 158).

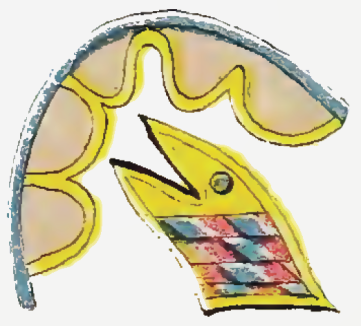

Once the initiate had succeeded in this task, however, they were believed to have at least some of the powers of Mishibizhiw and the other powerful yet dangerous manitous at their disposal. Some of the images from birchbark scrolls reproduced in Tanner’s narrative, for example, illustrate songs in which the mide identifies snakes or Mishibizhiw himself as their “friend” or helper in their healing or other rites (e.g., Tanner 1830:345-347, possibly 376-378). Kohl (1985:150-152; 1859:207-210) also examined a Midewiwin scroll held by the Fond du Lac, WI chief Maangozid in which the square representing the fourth degree had three “paws of the ‘Great Lion’” in it (“Tatzen des ‘großen Löwen’”; shown below), though Kohl did not understand the reference. It may also be noted that the number four is a spiritually and symbolically significant one in the traditional Anishinaabe world, as it is for most Indian peoples, while the number three is at best meaningless, or at worst is associated with darker powers.

Furthermore, the miigis (a small seashell, in post-contact times usually the cowrie Monetaria moneta), one of the most sacred objects in the Midewiwin, and the symbol of the society—and, in some versions of the Midewiwin origin myth, the carrier of the Midewiwin itself to the people—was “said to appear on the surface of a lake when the action of a manido causes the water to seethe” (Densmore 1979:88), or were even “thought to be the scales . . . of the Underwater panther” (Howard 1977:141). Densmore (1910:14) also reported that it was “not unusual for a member of the Mĭde´wĭwĭn to sit beside the water for hours at a time, singing Mĭde´ songs and beating the Mĭde´ drum or shaking a rattle” in the hopes of a “visitation” from a water manitou. This is part of the broader idea that “power” gained from Mishibizhiw is by means of possession of a physical part of his body—as a slice of his horns, as pieces of copper, or as miigis shells, both of the latter two viewed as his scales.

Midewiwin instruction constantly emphasized to initiates the importance of staying on the correct “Path of Life,” acting with moral rectitude and not succumbing to the temptation to pervert their newly acquired powers for selfish or evil means; but the very fact that this was such a strong emphasis is an indication that such perversion was not uncommon. Mideg of higher degrees, especially of the fourth degree and above, were widely perceived by other community members as often being evil and sometimes murderous sorcerers, and viewed with the same combination of awe, reverence, and terror with which Mishibizhiw himself was viewed.[14]

There is one final, crucial link between Mishibizhiw and the Midewiwin, but we will hold off discussion of this link until later in the post.

One final connection between humans and Mishibizhiw which has not been mentioned is the role played by a serpent in the path that the souls of the dead must take to reach the afterworld. This involves a four-day journey toward the west (or south), where the Land of the Dead is located. Along the way, there is a sweet berry, usually a strawberry, by the side of the path, sometimes with a being next to it urging the soul to take it, but the soul must resist temptation and avoid eating it, or they are extinguished. There are usually other trials as well, such as a giant dog blocking their way. Finally they reach a raging river, which they must cross over a rocking log. If they fall off, they fail to reach the Land of the Dead and are turned into frogs, toads, or fish instead, or simply cease to exist. If they successfully navigate the river/log to the other side, they enter the afterworld. However, as is repeatedly clarified when Anishinaabe cosmology is explained to outsiders, the “log” is not really a log, but a horned serpent, either Mishibizhiw (/Mishiginebig) himself or one of his underlings. Navigating treacherous waters, by means of the god of waters himself, is thus the final step required to obtain a place in the afterlife—and those who fail the navigation end up as his minions if they are not extinguished altogether.

In all of the preceding discussion, it may appear as though Mishibizhiw is simply an evil manitou. Certainly some outsiders and even some later Anishinaabeg have drawn this conclusion. It didn’t exactly require a great leap for plenty of Christian missionaries to make a connection between Satan and this horned, long-tailed monster of the underworld who was deeply associated with serpents (or even pictured as one). And on the ever-reliable Wikipedia we can find the statement: “The Algonquins and Ojibwe believe that the cougar lived in the underworld and was wicked.” But although he does have a malevolent aspect, this misses Mishibizhiw’s true essence. Mishibizhiw is incredibly dangerous, responsible for rapids and whirlpools and eddies and undertows and swamped boats and squalls and quicksand and missing children and drowning. Mishibizhiw is incredibly powerful, reigning over all of the lands under our own and over the waters—and the fish within them—that are vital to Anishinaabe life, while exerting an erotic fascination on the part of women and a great temptation for power on the part of both sexes. Mishibizhiw is unpredictable, appearing when least expected, traveling from lake to lake through hidden tunnels, and sometimes even offering his powers to people, though often at a terrible cost. But Mishibizhiw is not evil. He is a force of great power, great danger, great uncertainty, and great mystery, and deserving of the utmost respect.

Mishibizhiw is the embodiment of water itself, with all its chaos and uncertainties and dangers and mysteries, with its unplumbable depths. He is, as Erdrich says, “death by drowning,” one of the most feared means of death for the Anishinaabeg: “the death a Chippewa cannot survive.”

But although Mishibizhiw and the other underwater manitous present many dangers to humans, humans also have great and powerful allies who can help keep them subdued on our behalf.

The Thunderers

My great-grandfather used to tell us that the birds were our friends, and would kill the snakes and the dragons. . . . So at a certain length of time the clouds pass over a place and you see the fire going into the water. The birds are killing the dragons.

—Elizabeth Philemon in Dorson, Bloodstoppers and Bearwalkers, pg. 40

Bekhokhó ragá haYám,

uvitvunató mákhats Ráhav,

Berukhó ⸢sam Máim⸣ shifrá,

kholelá yadó Nakhásh baríakh.

Hen éle ktsot drakháv,

umá shémets davár nishmá bo?

veráam gvurotáv mi yitbonán?With His power He subdued the Sea,

and with His cunning He smashed Rahav,

With His wind He bagged the Waters,

His hand cut down the twisting Serpent.

Look, these are but the least of His ways,

what mere whisper of a word do we hear of Him?

and the thunder of His might who can grasp?

—Job 26:12-14[15]

These allies are the animikiig or binesiwag, translated “Thunders,” “Thunderers,” or “thunderbirds.” Animikii also means “lightning bolt” and can form the verb animikiikaa “there is a thunderstorm,” literally “there are many Thunderers/lightning bolts,” while binesi contains the root bine- “bird” and can also refer to any large bird, especially raptors. Thunderers are likely to be more familiar to non-Indians; “thunderbirds” have penetrated into the white popular consciousness while “Great Lynxes” have not.

Conceived of as both the cause of thunderstorms and as immanent within them, Thunderers are usually pictured as giant, hawk- or eagle-like birds, though they were occasionally viewed as humanoid beings with wings, and like most manitous they are able to shapeshift, so they can appear to people in human form. The identification with birds is reinforced not only by the often rather bird-like shape of thunderclouds, but also by their behavior. Like many other birds, they are migratory, appearing only during the warmer months and vanishing in winter. (Though admittedly many other manitous, including Mishibizhiw, are inactive during winter.) And “like birds of prey, [they] travel through the sky on currents of air, striking the earth in search of food” (Smith 2012:76). Unlike with Mishibizhiw, where there are multiple and quite disparate forms in which he has been conceived and represented in images, there is a very standardized Thunderer motif, which is similar or identical to the motif used for normal raptors as well. Interestingly, while Mishibizhiw is almost always illustrated facing the viewer head-on, Thunderers are almost always illustrated with their heads in profile:

As with Mishibizhiw, Thunderer images were frequently added to bandolier bags, clothing, and other items. In fact, it was very common to represent Mishibizhiw on one side of a bag and Thunderer(s) on the other.

This type of image has continued to be popular in modern times:

The noise of thunder itself is either caused by the beating of the Thunderers’ wings or is considered to be the sound of their voices as they speak. A. Irving Hallowell (1975:158) relates the following anecdote from his time working with the Ojibwes of Berens River:

There was one clap of thunder after another. Suddenly the old man turned to his wife and asked, “Did you hear what was said?” “No,” she replied, “I didn’t catch it.” My informant . . . did not at first know what the old man and his wife referred to. It was, of course, the thunder. The old man thought that one of the Thunder Birds had said something to him. He was reacting to this sound in the same way as he would respond to a human being, whose words he did not understand.

Like Mishibizhiw, there are multiple Thunderers. Sometimes there are specifically four or eight, or at least four or eight primary ones, associated with the four Winds and cardinal directions; but other people believe there exist an indeterminate number of them. Unlike Mishibizhiw, however, who almost always seems to live and travel alone, the Thunderers come in groups. Thunderstorms represent the presence of multiple Thunderers, and when humans have been able to observe their nests (see below), they find that they live in families or even larger societies. Thunderers thus accord with the normal Anishinaabe social order, in which people are dependent upon one another, and familial, clan, village, and other interpersonal relationships carry great importance, while Mishibizhiw, despite representing a multitude of individual beings, generally remains outside this order, an alien in a world where social bonds are so crucial.

As noted, Thunderers are generally seen as some sort of giant bird of prey; while thunder is their voice or beating wings, lightning flashes are produced when they open their eyes, and lightning bolts are them hunting for prey, the arrows or “thunderstones” (baaginewasiniig) which they fire at their victims. And their prey is Mishibizhiw and the other underwater and underground manitous, especially serpents. As we have seen, Mishibizhiw holds incredible power—but the Thunderers hold more, and are almost always victorious in their hunts. As Smith (2012:134) notes, in the battle between Thunderer and Mishibizhiw, it is always the Thunderers who are aggressively “on the offensive.”

The Thunderers are thus vital to humans not just for bringing life-giving waters, but for continually keeping the dangerous manitous in check. As Andrew Blackbird (1887:103) put it—though, as a Christian convert, with an overemphasis on the “evil” aspect of underworld manitous—the Thunderers “water the earth and . . . keep down all the evil monsters that are under the earth, which would eat up and devour the inhabitants of the earth if they were set at liberty.”[16] By ridding bodies of water of their manitous, Thunderers also help cleanse these waters and return fish to them. Andrew Medler tells a story from when he was a boy (Bloomfield 1958:190-191), in which he noticed that a spring from which he had gone to fetch water was “dirty” (wiinaagmi) and “muddied” (bkwebiigmi). He realized: “It seems as if there may be some creature in the spring from which we get the water” (“gnabaj ⸢wya⸣ wesiinh yaadig maa ndahbaaning”), and his grandfather assured him that there would soon be a thunderstorm. The next night there was indeed a great thunderstorm, and “[o]nly then did the water flow, in the morning” (Mii eta nbiish gaa-bmijwang gegzhebaawgak).

Finally, Thunderers help the world not only by cleansing bodies of water, but by creating the fires which renew the earth and allow the flourishing of new growth.

People are usually unable to see when a Thunderer actually captures its prey, for as they dive down to grab it, they are enveloped in clouds or fog or otherwise obscured. For example, in a story about a giant leech manitou that used to live in Leech Lake, MN, Dorothy Dora Whipple (Mezinaashiikwe) describes how the Thunderers came to attack and remove the leech from the waters (Whipple 2015:3; brackets in the original):

There were people around the lake on a perfectly clear day, not a cloud in the sky. Then they saw a very small dark cloud coming from the north. It was coming very, very fast. It came right above the leech. Then the cloud was there in the middle of the lake. And they [the thunderbirds] made lots of thunder, really loud thunderclaps. They killed the leech. Then it got really foggy and it rained. That’s when the leech disappeared.[17]

Similarly, Coleman (1937:37) reports that “[w]hen they [the Thunderers] dived down into the water and brought up the wicked spirits in their claws . . . the whole place was enveloped in fog.” And interestingly, Elizabeth Philemon, a Potawatomi from Hannahville, MI, told Dorson (1980:39) a story in which a Thunderer gives a young chief various powerful gifts, including “a rare little stone to make a fog.”

However, sometimes people can glimpse the underwater manitou itself as it is taken up. Raymond Armstrong of Manitoulin told Smith (2012:136) of an old woman he knew who was sitting by her window overlooking Lake Huron during a thunderstorm: “And she seen all kinds of fire, lines of fire going back and forth at that bay—like as if it was searching. Every now and then there would be a big Thunder. At one time her whole house shook.” Then suddenly “she seen this all [sic] fog, it was all fog, water. And she seen this big thing. They used to say it was about seven or eight feet wide in diameter that was going up in the sky. And she saw the tail end of it. It was going like this [a whirling movement -Smith’s interpolation]. It was a big snake—maybe fifty, sixty feet, or a hundred feet long.” Peter Jones (Gakiiwegwanebi) (1861:86) also says that “[s]ome Indians affirm that they have seen the serpent taken up by the thunder into the clouds.”

Just as Mishibizhiw is associated with an awesome and potentially deadly force of nature, so too are the Thunderers. Yet while Mishibizhiw is feared, the Thunderers generally are not. They are addressed as “Grandfather”/“Grandmother” and welcomed as extremely propitious and powerful visitors when they appear in dreams or as bawaaganag in visions. Upon their arrival in thunderstorms, they should be given an offering of tobacco as a sign of respect and thanksgiving—though this offering also serves, somewhat as in offerings to Mishibizhiw, as a request that they pass by in peace. Unlike Mishibizhiw, who according to at least some Anishinaabeg may still choose to drown you even if you show him respect, the Thunderers view humans kindly, and as long as they are shown proper respect they will not harm someone. As Mrs. Joseph Feathers of Nahma, MI told Dorson (1980:56), “Best thing to do is burn tobacco and say, ‘That’s for you, granddad.’ They’ll protect you.” Several of Smith’s consultants in fact insisted that Indians are never struck by lightning, only white people, and Mrs. Feathers made the same claim.[18] When threatened by Mishibizhiw or one of his underlings, humans can even directly call on the Thunderers for help. For instance, Barnouw (1977:226) relays the report of an Ojibwe man from Lac Courte Oreilles, WI, who “was once chased by a supernatural snake about six or seven inches in diameter. He managed to reach home and . . . . smoked [his pipe] and called upon the thunderbirds for help. Soon some clouds appeared in the sky; then a thunderbolt came down and killed the snake.” Then “one of the thunderbirds carried the snake away.”

There are two exceptions to these statements. The first is found in a widespread traditional story which takes place in the far distant past, evidently from a time when Thunderers did not subsist solely on underworld manitous. The Thunderers ask some mosquitos where they have found all the blood they eat, and the mosquitos protect humans by lying that they have gotten it from trees (i.e., sap). The Thunderers attack the trees in order to feed—explaining why trees are so often struck by lightning—and humans are spared. Thomas Sandy of Rama, as reported by Laidlaw, is explicit on this last point, saying that “if they had told the Thunderbirds where they did get the blood, all the Indians would have been killed” (Laidlaw 1927:54).

The other exception involves young Thunderers. As noted, Thunderers, like humans, live in families, and have children. Their children, however, have not yet learned how to properly harness and control their powers, and may accidentally unleash them against innocent people. James Redsky (Ishkwe-Giizhig) of Shoal Lake, ON explains that “when the young thunderbirds go by, they cause destruction because they don’t know any better. . . . They knock down trees with lightning from their beaks. Houses are struck and smashed also. The older thunderbirds try to correct these foolish young birds, but they do not learn because they are so young” (Redsky 1972:110-111 quoted in Smith 2012:84). Smith notes, however, that “[t]his destructive behavior is never understood as malevolent.” A few earlier white observers did describe the Thunderers as evil, e.g., Hoffman (1891:158, 163) (“malevolent” and “malignant”), but this is not an accurate reflection of the traditional Anishinaabe worldview; presumably Hoffman (and others) inadvertently imposed their own bias in which thunderstorms are dangerous and therefore “bad.” Hoffman also viewed the jiisakiiwininiwag or Shaking Tent shamans, whom he said derived their powers from the Thunderers, as evil, which probably contributed to his negative evaluation of Thunderers themselves.

How do Anishinaabe people know the social and family lives of Thunderers? Aside from someone learning of them through dreams or visions, there are a number of accounts of humans who have visited Thunderer nests, either of their own initiative or after being taken there. One common version has one or more men deciding to figure out what is causing the loud thunder they hear, so they scale the mountain where a Thunderer nest is located (e.g., P. Jones 1861:86-87; Radin 1914:59; Jones 1919:190-193; Radin and Reagan 1928:145-146; Smith 2012:83-85). The precise details of what they discover vary, but usually include multiple Thunderers of different ages including young ones—again, indicating that they have human-like families—as well as the bones of the serpents on which they’ve been feeding. Peter Jones (1861:86), for example, describes the scene a man in such a situation encounters: “I saw the thunder’s nest, where a brood of young thunders had been reared. I saw all sorts of curious bones of serpents, on the flesh of which the old thunders had been feeding their young; and the bark of the young cedar trees pealed [sic] and stripped, on which the young thunders had been trying their skill in shooting their arrows before going abroad to hunt serpents.” Similarly, in Radin and Reagan’s (1928:145) version collected at Sarnia, ON, the two young men who reach a nest discover “many snake bones because the birds eat nothing but snakes.”

In some cases the men are treated courteously by the Thunderers, but more often they are punished for disrespectfully violating the Thunderers’ home. In Gaagige-Binesi’s version told to William Jones (1919:190-193), two young men, after fasting for eight days, scale the mountain which the other people are afraid to approach due to the constant sound of the Thunderers. There they find two adult Thunderers and two young Thunderers, but clouds quickly obscure the nest; one of the men has seen enough and decides to turn back, but his companion insists on staying, and is struck by lightning and killed. (Similar stories are still told to this day.) On the other hand, in Radin and Reagan’s version, despite one of the young men initially shooting an arrow at the first Thunderer he sees in the nest (!), the Thunderers invite the boys into their lodge, tell them stories, and have them spend the whole summer with them, including accompanying them, in the form of clouds, on their hunts for horned snakes. At one point the narrator even says, “The old Thunder told his children (including the two young men) to go along quietly . . . ,” suggesting the men have essentially been adopted by the Thunderers. In a different kind of story from the Plains Ojibwes (Skinner 1928:161-162), a young boy is taken by some Thunderers to their home for four days. They tell him not to watch them eat, but he does so anyway and sees they are eating “enormous snake[s],” although they feed him “Indian food.” They return him home, “[b]ut the four days and nights were four years. They took him home and he was a grown man.” The idea that a brief period of time for manitous is a long period of time in the human world—and more specifically, that a manitou day is equivalent to a human year—is a recurring and very widespread one, and with parallels throughout the world.

Thunderers can attack the underworld manitous directly, or they can do so indirectly, by providing humans with some of their powers and thus having humans act as their proxies in this war. For example, in the stories mentioned earlier in which some girls in a boat are nearly pulled underwater by Mishibizhiw before one strikes him with her paddle, severing part of his tail (Jones 1919:258-295; Radin 1924:513-514; Barnouw 1977:132-133), I left out one important detail. In Pete Martin’s version in Barnouw, the girl who strikes Mishibizhiw says “Thunder is striking you.” This may at first seem like simply her way of trying to frighten Mishibizhiw, but the versions of the story in Jones and Radin provide the real explanation. In Gaagige-Binesi’s version in Jones the girl, as she strikes Mishibizhiw, says: “While I was young, I fasted for visions often. And at that time the Thunderers gave me their war club” (“Megwaa gii-oshkiniigiyaan moozhag ningii-makadeke. Mii dash iwapii Animikiig gii-miizhiwaad obagamaaganiwaa”). In Radin’s version her wording is similar: “When I was fasting I was blessed by the thunder-spirits.” In other words, the bawaaganag she acquired during her vision quest were the Thunderers, who have provided her with their own power to vanquish Mishibizhiw, thus transforming her paddle into a Thunderer’s weapon.

Interestingly, there are a couple of Plains Ojibwe stories, which have parallels in several neighboring cultures, in which humans bafflingly side with an underwater manitou over a Thunderer, with predictably disastrous consequences. In one (Skinner 1928:161), two men see a Thunderer grab what is named as Mishiginebig out of a lake. “The snake wept; he said he had dreamed of two young Indians who would give him life.” One of the men then shoots the Thunderer, who drops Mishiginebig and admonishes the men, warning them, “You’ve made a big mistake not to help me, for Micekine´bik will soon take you.” A decent period of time evidently passes, but one day as the men are collecting eggs in a knee-deep swamp, the one who shot the Thunderer “saw a whirlpool twisting before him. Laughing, he was carried along.” Later that year Mishiginebig kills the other man as well. Another version (Skinner 1928:169) is very brief: “A thunderer once pounced on a huge snake and entangled his claws in its back. Neither could escape. A passing Indian, being asked by both for help, shot the thunderer, whereas he should have killed the snake.” The story ends with the somewhat enigmatic comment: “There underneath snakes do not steal children, but subterranean panthers do,” which at least indicates that Mishiginebig (or perhaps serpentine underwater manitous generally?) were kept distinct from Mishibizhiw for the narrator.

Just as there are traditional stories in which women marry serpents, there are stories in which men or women marry Thunderers (in—at least initially—human form) (e.g., Radin 1914:75; Jones 1919:132-149; Skinner 1919:293-295; Radin and Reagan 1928:135-137; Ray and Stevens 1971:88-92; Hallowell 1975:156-157; Morrisseau 1965:7-8 cited in Smith 2012:91-92). While these aren’t as thoroughly negative as the “serpent lover” stories, they nonetheless tend to be at least ambiguous, often featuring serious violence, or death or presumed death, and reflecting a degree of antipathy or, one might say, xenophobia, between Thunderers and humans not present elsewhere in Anishinaabe thought and mythology (but a normal feature of stories that involve humans marrying non-humans). Jones’s, Skinner’s, Ray and Stevens’s, Hallowell’s, and Morrisseau’s stories are all variants of a very common tale, in which early on the Thunderer wife is shot by her husband’s eldest brother out of jealousy, though she does not die; in fact in several versions, after a long quest by the husband, she and her sisters marry all his brothers in turn. In Radin and Reagan’s version, the Thunderer woman’s husband must hide from her brothers, who it’s said will be angry if they learn who he is. (And later the child of their union is stolen by an underwater manitou, though they oddly seem to take this in stride.) In Ray and Steven’s version the Thunderers conclude that it is impossible for a human to live with and like a Thunderer, and send the Thunderer woman and her human husband away to spend their lives on the earth. Radin’s very short version of a woman taking a Thunderer husband is the only one without any real negative undertones or evidence that Thunderers and humans disapprove of intermarriage.

Thunderers did not occupy anywhere near as central a role in the Midewiwin as Mishibizhiw did. However, Hoffman (1891:176) does state that according to his consultant Ziigaasige of Mille Lacs, MN, the second degree “is owned by the Thunder Bird”—though elsewhere Gichi-Manidoo, the creator god, is identified by a different consultant as “the guardian of the second degree” (Hoffman 1891:182). Thunderers are also mentioned in several Midewiwin songs.

One mention of the Thunderers could be interpreted as referring to a role as guardians of the Midewiwin, but it rather seems to reflect their more general role as punishers of those who egregiously transgress moral boundaries or defile sacred spaces, items, or rites. In a powerful passage, Waasaagoneshkang or possibly Midaasoganzh has the manitou who transmits the Midewiwin to the Anishinaabe people tell them (Jones 1919:568-571):

O’ow idash Midewiwin gaawiikaa da-wekwaashkaasinoon. A’aw wayaabishkiiwed giishpin wii-maji-idang Animikii da-nishkaadizi. Oga-biigwa’aan i’iw oodena; misawaa gichi-michaag i’iw oodena booch oga-niigwa’aan a’aw Animikii. Giishpin goda aapiji-wii-paapinendang a’aw wayaabishkiiwed, mii iw ge-izhichiged a’aw Wegimaawid Binesi. Aapiji-manidoowi, gaawiin gegoo oga-bwaanawitoosiin. Booshke gichi-asiniin, mii go iw ji-niigwa’waad.

But this Midewiwin shall never come to an end. The white man, if he would speak ill of it, the Thunderer will grow incensed. He will shatter [his] town; no matter if the town is enormous, the Thunderer will break it all to pieces. If the white man should thoroughly mock it, that is what the Chief of Birds will do. What a manitou he is; at nothing shall he fail. Though it be a great rock yet he can break it all to pieces.[19]

There is a temptation to view the cosmic battle between the forces of the air, the Thunderers, and the forces of the depths, Mishibizhiw and the underwater manitous, as a battle between “Good and Evil.” It was seen as such by many earlier white Christians, and is presented as such by some modern Anishinaabe people too, whether or not they are Christian. But this rather simplistic dualism seems to be pretty clearly due to Christian influence; there is no good evidence that earlier Anishinaabeg originally conceived of the manitous this way.[20] Rather, the conflict was one in which the ideal outcome was balance, not destruction of “evil.”

Indeed, as we have already seen, while Mishibizhiw is very dangerous and has many “negative” qualities, he is not purely evil, and in fact has on occasion helped people, as their bawaagan or otherwise. In fact, in one rather extraordinary story, Mishibizhiw actively intervenes to save someone’s life through no apparent prompting or request, and demands nothing in return. Radin (1924:501-502) relates the story from a consultant near Sarnia, ON of a man who falls through the ice during winter and is “seized by a lion” who “take[s] him home with him.” They spend the winter in Mishibizhiw’s underwater home, with the manitou providing him with food. Once the ice melts in the spring, Mishibizhiw has “his children” carry the man safely back to the surface, saying, “I hope you will some time think of me for I had compassion for you when you broke through the ice.” Yet the same narrator gives other stories in which Mishibizhiw kills and attempts to kill people. Clearly he is a complex figure, capable of acts that affect humans negatively but also ones that affect humans positively, equally capable of drowning someone or providing someone with a bounty of fish and safe passage across a lake.

Likewise, the Thunderers, though seen in a more positive light than Mishibizhiw, are capable of actions that both help and harm humans. They may keep the forces of the depths at bay and provide many Indians with great power as bawaaganag, but their young can wreak destruction, and people who too boldly transgress moral boundaries or the sanctity of the Thunderers’ homes may be killed for their presumption. Few manitous were or are seen as purely good or purely evil; instead, like humans themselves, manitous possess complex personalities, and are capable of both “good” and “evil.”

Ultimately, the battle between Thunderer and Mishibizhiw, the battle between the two greatest forces in the Anishinaabe universe, the waters and the storms of the air, is a battle that has no end. The underwater manitous, and Mishibizhiw himself (themselves) may be killed a million times over, yet they remain present still, to be killed and reappear again. As David Migwans, one of Smith’s consultants, put it, “Nobody ever really wins” (Smith 2012:130). And indeed, as Smith (2012:137-138, 140-141) points out, both the Thunderers and underwater manitous, perversely, need one another. Though part of the Thunderers’ purpose on earth is to keep humans safe from underwater manitous, they depend on these manitous for food—in all the narratives in which humans observe their diet, they only subsist on serpents/underwater manitous. Meanwhile, the domain of Mishibizhiw and his underlings is the water, and without the rains provided by the storms their home and kingdom would evaporate into thin air.

This need for balance, this interdependence and “blurring of boundaries” between Mishibizhiw and the Thunderers, between water and thunderstorms, underworld and skies, is also found in Anishinaabe iconography. One example is the very common practice of picturing Mishibizhiw and Thunderers on opposing sides of the same bag, already discussed and illustrated above. A second is observed by Corbiere and Migwans (2013). Beyond the quite concrete images used for Mishibizhiw and the Thunderers shown earlier in the post, they can be represented much more abstractly—the Thunderers as an hourglass figure, a radical simplification of their concrete representation; and Mishibizhiw as a spiral or diamond/octagon, apparently representing whirlpools. But here’s where it gets interesting: Corbiere and Migwans point out that there are images of Mishibizhiwag which include hourglass shapes within their bodies, and images of Thunderers which include spirals within their bodies.

Corbiere and Migwans (2013:44) compare this with “the Anishinaabe adage that everyone must bear within them something unbearable” and give as an example Maude Kegg’s (2011:14-15) quoting her grandmother’s description of a windigo—a giant maneating monster with a heart of ice, originally a human who resorted to cannibalism—as having “ice he must bear within himself” (“maagizhaa . . . mikwamiin awiiya iidog gegishkawaagwen”, where—as they note—the verb gigishkaw “to bear in or on one’s body; wear” is frequently associated with pregnancy, and in some dialects actually just means “be pregnant” or “give birth”). While windigos may now be frightful ~cannibal ice monsters~ they were once human, and their heart of ice, representing the loss of this precious humanity to the brutality of winter and its terrible temptations when starvation sets in, is an “unbearable burden.” By the same token the interrelationship and interdependence of Mishibizhiw and the Thunderers is simultaneously necessary and unbearable to both—and hence, iconographically, both carry the burden represented by the other. In their interdependence, and their struggle for supremacy which only leads to balance, each carries a piece of their mortal enemy.

The Anishinaabe world, then, is far richer and more complex than simply a stage where Good and Evil wage a battle over the fate of humanity, and where the creatures of the depths are mere “monsters” to be destroyed.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the origins of the Midewiwin and of humanity itself; but to understand that, we must first look at the origins of our current world, and the pivotal role that Mishibizhiw played in bringing it about.

The Deluge

But beneath, the Evil Spirits

Lay in ambush, waiting for him,

Broke the treacherous ice beneath him,

Dragged him downward to the bottom,

Buried in the sand his body.

—Longfellow, The Song of Hiawatha, Book XV

Er verlebte den ganzen Reſt des traurigen Winters in Einſamkeit und Betrübniß. Aber er wußte wohl, wer ſeinen Bruder getödtet hatte. Es war der Schlangenkönig, dem er jedoch im Winter nicht beikommen konnte.

Als es endlich Frühling geworden war . . .He spent the whole rest of the sad winter in loneliness and sorrow. But he knew well who had killed his brother. It was the Snake King, yet during winter he could not get at him.

But at last spring arrived . . .

—Kohl, Kitschi-Gami, Erster Band, pp. 323-324

Ezhi-odaapinaad ogii-gashkaakonijaandamini,

eyiidawinik odakonamini i’iw aki;

gaye ozidaaning, eyiidawizid ozidaaning ateni i’iw aki.

“Aaniish mii sa i’iw ji-gashkitooyang ji-ozhitooyang i’iw aki,” ogii-inaa’.As [Nanabush] picked [Muskrat] up, he was holding it tightly clenched in his paws,

in both paws he was holding that earth;

and in his feet, in both of his feet there was that earth.

“Well, now we will be able to create the earth,” [Nanabush] said to them.

—Waasaagoneshkang in Jones, Ojibwa Texts: Part I, pp. 152-153

There at least 50 written versions of the Anishinaabe creation myth cycle, probably many more, not to mention the versions still being retold orally. As might be expected, they vary in content over time and space, from narrator to narrator, based on the setting of the telling and the needs and interest of the audience, and many other variables. Nonetheless, there is a basic core that remains reasonably consistent. Here I’ll summarize this core, but it should be firmly kept in mind that most versions of the myth diverge from it in at least some details.

The origin myth is actually part of the much larger and varied collection of tales about the culture hero and trickster Nanabush (Ojibwe Nenabozho, Wenabozho, and a number of other variants, including in some northern communities the alternative name Wiisakejaak, the name of the equivalent Cree figure; his name in Potawatomi is Wiské), though the origin myth cycle only follows certain specific episodes of the Nanabush corpus of tales. In any event, we will pick up the story as Nanabush joins a pack of wolves one winter. They’re not especially keen on having him along, and he continually disregards their advice and instructions, resulting in predictable negative consequences for Nanabush and culminating in an episode where he injures or kills one of the wolves out of spite (though he pretends it’s an accident, and brings him back to life). The wolves decide to part with him, but they leave one of the young wolves with Nanabush to serve as his companion and hunter for the rest of the winter. While this companion may variously be described as Nanabush’s “brother,” “nephew,” “cousin,” “son,” or “grandson,” I’ll refer to him as his brother from now on since that’s the most common way the relationship is perceived.

Nanabush’s brother is an exceptional hunter, and provides them both with a great deal of food during the winter. At some point, Nanabush has a dream warning him that his brother will be killed if he crosses or jumps over a stream without laying a stick or log across it. He warns his brother of this, but soon afterward the brother, hot on the heels of an animal he’s chasing, neglects to do so at one small streambed; it either suddenly turns into a giant river as he jumps over it or he falls through the ice, and drowns, murdered by Mishibizhiw. Mishibizhiw here appears to be acting in his role as controller of access to fish and land game: while some versions of the story don’t attribute a motive to the wolf’s killing, in many cases it is explicitly tied to his success as a hunter. In these versions, then, Mishibizhiw is essentially removing someone who represents a threat to the game supply.

Nanabush is distraught over his brother’s death, and determines to avenge him. He comes upon a kingfisher, who tells him that Mishibizhiw is the one who killed his brother and gives advice on how to defeat him: specifically, where Mishibizhiw comes up on land with his guards and underlings to sun himself, and where to shoot Mishibizhiw in order to kill him (in his shadow, which contains one of his souls, and not in his body). Nanabush goes to their sunning spot as pointed out by the kingfisher, and transforms himself into a stump as a disguise. A host of underwater manitous soon come up onto the beach, including the chief Mishibizhiw. There follows an episode in which the manitous notice the stump, and several of them are sent to test it to make sure it’s really a stump and not Nanabush in disguise. Despite a serpent wrapping tightly around him and a bear clawing at him, Nanabush is barely able to maintain his composure and remain as a stump, and the manitous are at last satisfied and go to sleep.

Nanabush immediately runs over to Mishibizhiw and shoots him, but regardless of whether he follows the kingfisher’s advice, Mishibizhiw is seriously wounded but not instantly killed, and all the manitous retreat to the water. At this point, in some versions, there is a temporary flood sent by the underwater manitous which Nanabush must escape but which eventually subsides, while in others there is no flood, and we move immediately to the next episode.

Searching for Mishibizhiw, Nanabush comes upon an old toad-woman, a curer who is helping to heal Mishibizhiw. Nanabush kills and flays her, and puts on her skin. Using this disguise he infiltrates the underwater manitous’ lair and enters Mishibizhiw’s lodge, where he is infuriated to see his brother’s pelt is being used as the entrance covering to the lodge. Under the guise of healing Mishibizhiw, he approaches, sees the arrow sticking out of the Great Lynx’s body, and shoves it in deeply, finally killing the god of the waters and exacting his revenge.

Or so it seems. As Nanabush flees the lodge, he trips some basswood fiber cords that have been set up all around the area as a sort of home invasion alarm, instantly alerting all the manitous to his presence. And of course Mishibizhiw—the mighty god of the waters, the one with endless avatars, the one who can be everywhere at once, the one who can be killed a thousand times by the Thunderers and still appear in every whirlpool and eddy to drown the unwary—Mishibizhiw cannot ultimately be destroyed, not even by the powerful Nanabush. Immortal as the waters themselves, in his terrible wrath he sends a torrent that floods all of the earth and wipes it from existence.

Nanabush survives, but barely, either by climbing to the top of the highest tree which stretches itself higher still for him, or by cobbling together a small raft. Surrounded by a handful of animals, he realizes he needs to create the world anew. He sends three of the animals diving down to try to retrieve some dirt of the original world from the bottom of the waters, but each fails and floats up dead, though Nanabush revives them. Finally, the fourth animal, Muskrat, succeeds. With the dirt Muskrat collects Nanabush creates a tiny island of mud. He then works on continually enlarging it, sending out animals to test its size each time. Finally he determines the world is big enough. Though his own actions and Mishibizhiw’s rage nearly destroyed everything in the cataclysm, a new earth has been created. And though the new earth can never be the same as the old one, life can continue.

The Mortals

Awenen,

Dewine,

Bemaaji’ag?Who is this,

Sick unto death,

Whom I restore to life?

—Midewiwin initiation song in Densmore, Chippewa Music, pg. 59

While the myth explaining the origin of the current earth has been relatively consistent, if differing in some details, there does not seem to have been any single Anishinaabe myth explaining the origin of human beings that was consistent across all communities. What does seem reasonably consistent is that humans were created after the Deluge and formation of the new earth; the old earth had been populated by animals and manitous (though sometimes manitous described as though they are people; this notion is also not completely consistent, for some Anishinaabeg do believe that humans existed in the old earth and were created a second time after the Deluge). The most “basic” version of the human origin story involves the creator god, Gichi-Manidoo, creating humans from some earth or clay by closing his hand around it and/or blowing on it, but this is probably at least partially of Christian origin. Most of the recorded human origin myths have been related in the context of Midewiwin teachings on the origin of both humanity and the Midewiwin itself, and it’s to these that I will now turn.