Last updated: January 5, 2023

| NOTE: I no longer hold certain of the opinions expressed in this post; in particular, I now believe Jean Bottineau could basically speak Ojibwe perfectly well, even if maybe not completely fluently and even if his stronger languages were French and English. I also strongly suspect that his father and paternal relatives had a significant influence on his acquisition of Ojibwe (and Cree). |

Introduction

Hi there. If you thought some of my last posts were long, STRAP IN.

In the course of doing research on an upcoming post, I’ve been reading through several Ojibwe wordlists and texts collected by the Swiss linguist and anthropologist Albert S. Gatschet in the late 19th century and currently held in the National Anthropological Archives at the Smithsonian Institution. To my knowledge none of them have been published anywhere, although scholars are certainly aware of their existence and words from them have been cited in various places. As a public service, I decided to transcribe and publish the content of (at least some of) the materials here so it’s easier for anyone who wants to reference them in the future. (Photographs of the manuscripts in question are online, so anyone wishing to look at the originals can do so, which is how I’ve been able to read them in the first place.) In many cases these documents, despite generally being relatively short, also offer some interesting areas to explore.

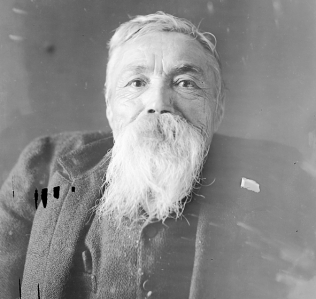

This post will deal with the chronologically earliest material, a 23-page wordlist comprising a variety of mostly basic vocabulary along with some clan names, band names and locations, and a very small handful of ethnographic notes, which was collected on May 28, 1878 from from Jean Baptiste Bottineau, a 41-year-old lawyer of Ojibwe and French ancestry from the Pembina/Turtle Mountain Band, and is found in NAA Manuscript 68, which also contains data collected by Gatschet from several other languages and sources.

The Bottineau vocabulary, consisting as it does mainly of basic vocabulary, might be thought to not be of particular interest in and of itself, as almost all the words can be found in other sources as well. However, there are some interesting points which can be noted concerning Gatschet’s field methods as well as Bottineau’s dialect, translation choices, and actual competence in Ojibwe, which I will discuss here.

The organization of the post is as follows (see also the fuller table of contents below):

- First, I give brief biographies of Gatschet and Bottineau (I will provide a fuller biography of Bottineau in the future).

- Second, I link to a verbatim transcript of the vocabulary and a retranscribed and reorganized list of the terms found in it—designed to present each of the words as originally written, the equivalent in the modern standardized southern Ojibwe orthography, and its accurate translation—along with an explanation of the notational and transcriptional conventions I’ve used.

- Third, I provide commentary on linguistic and other points of interest in the Bottineau vocabulary.

- Fourth, I give a list of all the words in the Bottineau vocabulary that I have not found attested elsewhere (although some surely are).

- Fifth, I conclude with a brief recapitulation of some of the most important things and interesting facts which the vocabulary demonstrates and which, as far as I know, have not otherwise been noted before. This can serve as a tl;dr section for anyone who inexplicably insists on not wading through a 50,000 word treatise (though there is some good stuff in the post!).

- Sixth and finally, I give an appendix with a photographic reproduction and discussion of the one word I’ve been unable to confidently read.

Albert Gatschet and Jean Bottineau

Albert Samuel Gatschet

Albert Samuel Gatschet (apparently pronounced /ɡa'ʃe/ [NCAB; Landar 1974:160, n. 2]) was born in Beatenberg, Switzerland, on October 3, 1832, and showed an interest in linguistics from an early age. He attended the Universities of Bern and Berlin, where his studies focused on languages, history, and theology. While he initially considered becoming a minister like his father, his love of languages and philology ultimately won out. Gatschet moved to America in 1868, where he became a language teacher and journal contributor. After publishing comparative studies of numerous languages of the American Southwest (= Gatschet 1875, 1876a, plus later Gatschet 1876b), he was hired by Major John Wesley Powell of the Geographical and Geological Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region in 1877 as a linguist/ethnologist, before moving to the Bureau of Ethnology at the Smithsonian upon its creation, with Powell as its first director, in 1879.

The Bureau under Powell had a very strong focus on American Indian languages, and Gatschet was an especially productive and prolific collector of linguistic data. He recorded vocabularies, texts, and ethnographic information from over a hundred languages and cultures from across the country, as well as working with older documentations collected by others. Partly in service of Powell’s principal goal of classifying all North American Indian languages, he also put his philological training to work and spent significant energy working on the classification of numerous languages and families (his strongest suit as a linguist). To take just one example, it was Gatschet who first demonstrated that Biloxi was a Siouan language; he also provided evidence for the connection between Siouan and Catawba. His research, along with that of fellow BAE linguist James Owen Dorsey, was the main source of data for Powell’s final, seminal 1891 classification (= Powell 1891). Gatschet ultimately produced at least 72 publications on Indian languages, mythology, history, and culture, in English, German, and French (Mooney 1907), though many were fairly short and circumscribed in scope. His most important contribution was a massive and well regarded two-volume work on Klamath and Modoc language and culture (= Gatschet 1890a, 1890b), which included texts, a grammar, ethnological/cultural notes, and a dictionary. Though flawed in many ways, Kinkade et al. (1998:63) observe it “was one of the first treatments of a North American language to present the structure of that language in its own terms.” Other important contributions included Creek and Hitchiti text collections accompanied by extensive commentary and historical and ethnological notes (= Gatschet 1884a, 1888), and the only truly extensive and reliable material—both vocabulary and texts—from Atakapa, later published, under John Swanton’s editorship and with some additional material, as Gatschet and Swanton (1932). He also published some articles on languages and cultures outside of North America and on linguistic theory.

Unfortunately, Gatschet’s experience at the BAE was in many ways far from ideal, and his difficulties were compounded by his own personality. While he had a few friends with whom he was close, including James Mooney, who joined the Bureau in 1885, he preferred to work alone and was generally perceived by others as cold and aloof (Landar 1974:160-161). From the descriptions I’ve seen, it seems as though Gatschet was closer to what we would consider today simply “socially awkward,” which manifested as a shyness and lack of interpersonal skills that were misinterpreted and poorly received by many of his colleagues at the time, with the exception of Mooney.[1] He became alienated from Powell and especially from Powell’s close friend and clerk, and the BAE’s resident bibliographer, James Pilling, and was never a member of Powell’s “inner circle” (Hinsley 1981:162).

Indeed, while Powell respected Gatschet as a data collector, he appears not to have thought much of him beyond that, or to have trusted him with much else. In spite of the relatively meager linguistic training and prowess of Powell and of his assistant Henry W. Henshaw (who did much of the work in producing the final 1891 master classification and linguistic map of American Indian languages) and in spite of Gatschet being a legitimately great comparative linguist for the day (no less a figure than Franz Boas called him “by far the most eminent American philologist, away ahead of all of us” [quoted in Hinsley 1981:180]), Powell and Henshaw made use of Gatschet’s collected data for the classification, but at times ignored Gatschet’s actual judgments regarding the data. For example, they failed to recognize a Uto-Aztecan family, as Gatschet did. In other instances they ignored Gatschet’s conclusions in favor of those of Dorsey or others, even when Gatschet’s were based on substantially more experience with the languages in question. And in the case of the determination that Catawba was related to Siouan they ignored Gatschet’s judgments until these were duplicated by Dorsey on the basis of the latter’s own work. (Alfred Kroeber, based on his acquaintance with many of the people involved with the early BAE, also “got . . . [the] impression that Powell leaned less on [Gatschet] than on some others for decisions in linguistics” [Kroeber 1993:46].) Unlike Gatschet’s practices as a comparativist (see, e.g., Gatschet 1876a:332, 1876b, 1879b), Powell and Henshaw also based the classification solely on visual inspection of vocabulary lists for seemingly obvious cognates—placing no importance on regular sound correspondences or on grammatical evidence (see Sturtevant 1959; Haas 1969:249-255; Darnell 1971:80, 86-89, 93; Campbell and Mithun 1979:10-12; Campbell 1997:57-61).

Powell’s evident view of Gatschet as being primarily useful for data gathering led to significant frustrations for Gatschet. Instead of being permitted to continue his in-depth work with the Klamaths and Modocs as he wished, he was increasingly employed as Powell’s and Henshaw’s “laboring work-horse and philologist clerk” (Hinsley 1981:162, quoting Colby 1977:49), sent on endless field expeditions to collect data for the classification, as well as for Powell’s planned “synonymy” of all American Indian tribes (which gradually ballooned into a two-volume encyclopedia), and finally to record and compare various Algonquian languages and dialects. As Gatschet was continually sent to conduct new fieldwork, he was never given the opportunity to edit and publish his extensive and accumulating past fieldwork. Boas commented that he “had accumulated such a vast amount of material that the only right thing for him to do would have been to sit down and write it out for publication. And he . . . would have . . . [done] so. His lack of publication is only a result of the policy of Major Powell, who wanted him to gather material for his general volume on the languages of the American Race” (quoted in Hinsley 1981:179).

Thus, while he had some key early publications, Gatschet published little of much substance in the last years of his professional life, and the bulk of his documentary work remains unpublished, in numerous field notebooks and file cards sitting in the National Anthropological Archives, as is the case with the Bottineau vocabulary. Nonetheless, many of these materials are invaluable, as they constitute some of the only quality documentation of many languages now long extinct, including a number of isolates (Goddard 1988). And lest this leave any misimpression, he and his writings were certainly well known to the scholarly world in both North America and Europe.

A sick and aging Gatschet retired from the BAE in 1905, and after a long battle with nephritis he died in poverty two years later on March 16, 1907, at the age of 74. Gatschet had married Louise Horner, an American, in 1892, but had no children.

Although the language never formed one of his primary focuses, Gatschet collected Ojibwe materials from several different consultants at various times during the first decade and a half of his career. In addition to the Bottineau vocabulary, he collected a three-page vocabulary in January 1883 (NAA MS 1449), 16 pages of vocabulary in March 1883 and a short text at an unclear date, possibly in 1896 (MS 66), 37 pages of texts and vocabulary in March 1889 (MS 1999), and three records of Kansas/Oklahoma Odawa: a 28-page vocabulary in November 1884 (MS 288), a collection of texts and vocabularies beginning in 1887 (MS 237), and an undated cleaned-up retranscription of part of the first text of MS 237 (MS 2001). It is also clear that he remained in contact with Bottineau long after the collection of the 1878 vocabulary. For example, in his field notebook of Odawa materials collected in 1887-1888 (MS 237), he has multiple notations indicating that in December of 1891 Bottineau assisted him with interpreting some of the material, as will be discussed in more detail in the “Commentary” section below.[2]

Jean (John) Baptiste Bottineau

Gatschet’s consultant for his 1878 vocabulary was no random member of the Pembina/Turtle Mountain Band. Jean Bottineau was part of an illustrious family, as well as one of the key players in what were among the most momentous events in the Turtle Mountain Band’s history.[3] To do justice to his story and the story of the Turtle Mountain people I’ve ended up abandoning my original plan to merely have a short biography of him here; instead, while I will summarize his biography briefly here, I will also present a fuller exploration of Bottineau’s life and the events in which he took part in an upcoming post.

He was born near the settlement of Pembina at the borders of North Dakota, Minnesota, and Manitoba (for a map that includes some locations relevant to Bottineau’s life, see below) on May 3, but sources conflict as to the year; I will go with 1837 for this post, and will discuss the conflicting evidence in the future post. His father Pierre was a renowned Métis voyageur and guide for numerous expeditions in the old Northwest, for whom Bottineau County in North Dakota is named. Pierre’s father was a French Canadian fur trader for the North West Company, and his mother was an Ojibwe woman. Jean married Marie Renville, another Ojibwe of the Turtle Mountain Band, in 1862, and together they had three daughters, one of whom died in infancy; another daughter, Marie Bottineau Baldwin, “the first woman of color to graduate from the Washington College Law School” (Barker 2014:1), would go on to be a lawyer, a feminist and suffragette, and an Indian advocate both from within the government as an employee of the Office of Indian Affairs and from without as a member of the Society of American Indians.

Jean Bottineau held many roles during his life, but the one for which he is best known, by far, is serving as the attorney for Chief Little Shell III (Ojibwe name Ayabiwewidang “Sits and Speaks ”) and members of the Turtle Mountain Band composed of both Métis and Ojibwes in their dealings with the U.S. federal government, between 1878 and shortly before his death in 1911. (I will be using the term “Turtle Mountain Band” here somewhat anachronistically, since in one sense they did not become a single political unit until 1905, and in fact divisions within the community have remained to this day. Just think of “Turtle Mountain Band” as convenient shorthand for “the group of Ojibwes and Métis who wintered at or near the Turtle Mountains along the North Dakota-Manitoba border by the early to late 1800s, were frequently interconnected through kinship ties and some cultural traits, and often shared a number of political goals and acted in concert as something at least vaguely resembling a single unit and under a single leadership structure.”)

This was not an enjoyable role. Bottineau was a trained attorney, but was up against forces which had little interest in acting legally or according to their own professed norms of justice. The American government unilaterally deprived the Turtle Mountain Band of the vast majority of their lands during the 1880s, aside from a miniscule reservation, before strong-arming “representatives” of the band to conclude an agreement (the McCumber Agreement) in 1892 to officially sell those lands; the people were paid one million dollars for just under ten million acres, leading to the McCumber Agreement’s common derisive nickname, the “Ten-Cent Treaty,” i.e. ten cents per acre. By comparison, agreements with other U.S. tribes from around the same time and/or place paid between about $1.25 and $2.50 per acre, while the average price for agricultural land at the time in Rolette County, where the reservation is located, was $7.00 per acre, and average values for agricultural land in other counties which the tribe relinquished under the agreement were $6.33 per acre in 1890 (in 1900, after more substantial white settlement and usage—and thus a better gauge of the land’s true value to the Americans—the number was $10.44 per acre); finally, the Indian Claims Commission later valued the land they relinquished at mostly $11.20 per acre (S. Doc. 444, at 3, 21, 37, 177; Barnard and Jones 1987:72-74; Richotte 2009:267; note that the ICC was calculating values from 1905, when the Agreement finally went into effect).

At the same time as the Ten-Cent Treaty was negotiated, hundreds of people were struck from the membership rolls of the tribe, including some members of a given family but not others. The agreement negotiations were conducted with a group, the “Committee of Thirty-Two”—which also decided on the individuals to be excluded from the rolls—whom the government agents claimed to have selected (or in fact, to have been directly “elected by the band” itself [S. Doc. 444, at 12]), and which did not include Chief Little Shell or any Ojibwe members of the existing tribal council. In fact, however, there is evidence that this was effectively a secret coup against Little Shell and the traditional leadership by the men who were later “selected”/“elected” as committee members, executed with the foreknowledge and support of—and then eagerly exploited by—the federal government (Marmon 2001, 2009).

Government agents continually ignored Bottineau’s protestations and demands for information and justification, and on more than one occasion banned him from the reservation on threat of arrest to prevent him from being able to influence events, provide legal advice, or present legal arguments on behalf of the band members. Little Shell and the old tribal council denounced the Committee of Thirty-Two as illegitimate and refused to sign the Ten-Cent Treaty, and the Turtle Mountain Band split into multiple groups, with some people moving to Montana, Minnesota, South Dakota, or Canada, and others remaining on the tiny Turtle Mountain Reservation or elsewhere in North Dakota. Embroiled in both internal and external political machinations and controversies, for the rest of his life Bottineau continued to fight against the Ten-Cent Treaty, for some sort of resolution to the tribe’s status, for justice to be done for them, and for the reinstatement of those denied enrollment. He died on December 1, 1911 at the age of 74 (under the reconstruction here), the same age as Gatschet—and, like Gatschet, of nephritis.

While all this is of course important in its own right, I will close by asking what Bottineau’s biography might tell us about the vocabulary which Gatschet collected. In the commentary, these questions will be examined again, and answers suggested, in light of what the vocabulary shows.

First, we know that Bottineau spoke both French and English; some of his correspondence with J. N. B. Hewitt (MS 3968 = Bottineau 1909) and a comment of Hewitt’s in Hodge (1910:289) indicates that he spoke at least some Plains Cree as well. His father Pierre reportedly spoke not only French, English, Ojibwe, and Cree, but also the Siouan languages Assiniboine, Dakota, Mandan, and Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) (“Pierre Bottineau”). I’m not aware of any evidence that Jean Bottineau knew any of these Siouan languages. It’s possible he also spoke Michif, the language of most Red River Métis and their descendants, given that the Métis were from the beginning the numerically dominant ethnic group of the Turtle Mountain people, that it was their language which by the 20th century was the non-European language used by all members of the community who spoke any language in addition to English (a handful of native Ojibwe speakers remained until relatively recently, but all of them also spoke Michif, and many other Ojibwes had already shifted to speaking only Michif in previous generations), and that many of Michif’s first speakers were of Ojibwe ancestry. I have not come across anything that would suggest he did speak Michif, however, and so the question remains unanswered.[4] He also, of course, spoke Ojibwe, as indicated by this vocabulary, but there are two questions to consider in this regard.

The first question is, what dialect of Ojibwe would he have spoken? He was a member of the Pembina Band (initially centered around Pembina, ND—along the Minnesota and Canadian borders—and the Pembina River; see footnote five below for the relationship between the Pembina and Turtle Mountain bands), which included people whose ancestors had originally come from various locations to the east—Little Shell’s ancestors for their part may have been from Leech Lake in north-central Minnesota or Mille Lacs in central Minnesota (Coues 1897:53-54; Murray 1984:16; Marmon 2001:34-36, 2009:21), but many band members’ ancestors were from Red Lake in northern Minnesota, while some were from other locations in central or eastern Minnesota, Rainy Lake or Lake of the Woods further north, or the northwest shore of Lake Superior, and some were even Odawas from further east, like John Tanner’s adoptive community—and Bottineau could have spoken any of several different (sub)dialects.[5] In fact, until it went extinct there a few years ago, two dialects of Ojibwe were still spoken on the Turtle Mountain Reservation, a variety of Saulteaux and a variety of Minnesota Ojibwe (Bakker 1997:124, citing p.c. from Richard Rhodes). His band affiliation thus indicates that Bottineau probably would have spoken either Southwestern Ojibwe or Saulteaux, but gives us no information beyond that.

In fact, though, we know a bit more about his family history, which might suggest an answer. His grandmother, Pierre’s mother, was Margaret/Marguerite, the cousin of Misko-Makwa, the head chief of the Pembina Band and the head Pembina signatory to the Old Crossing Treaty. Margaret Bottineau is said to have been born near modern Warroad, MN, on the southwest shore of Lake of the Woods (TOR United States ex rel. Detling v. Work, at 6), and her extended family to have had their “habits and ranges . . . on Roseau Lake and River, Lake of the Woods, Pembina River, Hair Hills and Turtle Mountain, [and] the upper Red River country” (Bottineau 1910b:14), which more or less describes the early territory of the Pembina Band and so is entirely consistent with her being Pembina Ojibwe. (Incidentally, there is a great deal of confused, conflicting, and/or inaccurate information on Bottineau’s genealogy out there, both on the internet and in some published sources, but I will go into more detail on this in the post dedicated to Bottineau and Turtle Mountain.)

As for where Margaret’s family ultimately came from, we have the likely answer from attempts by two of her grandchildren—both half-sisters of Jean Bottineau, by a later wife of Pierre’s—to be recognized as Indians by the federal government. First, in 1925, Agnes Detling (née Bottineau) petitioned the Office of Indian Affairs for a pro rata and future shares in annuity payments as a “Chippewa Indian of Minnesota” under the Nelson Act of 1889 (25 Stat. 642) as well as 39 Stat. 123 and 43 Stat. 95. In supporting her petition, she included both an affidavit of her own, as well as affidavits from six Red Lake Ojibwes (although it is never specified whether these individuals are enrolled tribal citizens). In her own affidavit, she states that Margaret “was a full blood Chippewa Indian woman of the Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians” from the region immediately south of Lake of the Woods (TOR United States ex rel. Detling v. Work, at 6). The affidavits from the six Red Lake individuals are all nearly identical to one another, and four of them include the phrase that Margaret “was a full blood Chippewa Indian woman of the Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians” (id. at 7, 8, 9, 10) and another that she “was always spoken of [by all the Indians in the neighborhood] as a full blood Chippewa Indian of the Red Lake Band of Chippewas” (id. at 12).

Second, in 1932 Laura Bottineau Grey applied to the Office of Indian Affairs for an allotment and annuities as a “one quarter (¼) Indian of the Chippewa Tribe of Minnesota of the Red Lake Band” which she had “continuously maintained by tribal relations,” stated that she had, “with her family, always been recognized as and affiliated with the members of the Red Lake Band of Chippewas from earliest times” and that “Pierre Bottineau, with his family, . . . were recognized as affiliated members of the Red Lake Band of Chippewas,” and referred to Margaret as being “of the Reindeer, or Ahdik Clan of the Red Lake Tribe” (Grey 1932).

It would thus seem that Margaret’s family was originally from Red Lake, in northern Minnesota. As Margaret’s birth by Lake of the Woods underscores, this should be taken to mean Red Lake territory in general, not necessarily the actual shores of Red Lake itself or its immediate environs: at the time of her birth, the area under the Red Lake Band’s control extended north up to Lake of the Woods and west past the Red River, with their hunting territory, at least, overlapping with that of the Pembinas for a while.

None of this should be surprising, since Red Lake was the most common place of origin for the ancestors of Pembina Ojibwes, and many of the latter retained strong kinship and other ties with the Red Lake Band/Tribe. A given Ojibwe band did not just immediately form as a new entity; they gradually budded off from one or more existing bands, with often a long period of continuing interaction and movement of people between the two semi-“independent” bands. (And even the boundaries between “established” bands were very porous and people easily could—and did—move from one to another.)

While this information on Margaret is useful, given his father’s absences from home while Jean was growing up, I think he is most likely to have been influenced by the language(s) spoken by his mother and the people around him—and here I have somewhat less information. His mother was Genevieve “Jennie” Larence (surname spelled a number of ways), also of Ojibwe-French ancestry, but I have found little reliable information about her background, beyond brief statements by Bottineau that she was “a Chippewa of a foreign tride [sic: tribe]” (Bottineau 1910b:16) and that she was three quarters Ojibwe and one quarter white (TOR Bottineau v. O’Grady, at 35, 271). There is some very tenuous circumstantial evidence that she may have been associated with Red Lake, but given Bottineau’s statement that she was from a different Ojibwe tribe than his father’s family, I’m not sure what to make of this evidence. Taking into account that much of the information I can find on Bottineau’s extended family seems to be unreliable, I have basically decided to ignore this (though see later in the post). From the movements of Pierre and the family, and other evidence, it is clear that Jean, although born near Pembina, spent most of his life in southeastern Minnesota. His early childhood was spent in the vicinity of Fort Snelling, before the family moved to St. Anthony, part of modern Minneapolis, when he was eight. His father helped found and moved to the town of Osseo—still in the vicinity of the modern Twin Cities—in 1855, when Jean was about 18. Even after leaving his parents’ household, he did not leave the area: his law practice was based in Minneapolis for most of his working life, until his relocation to Washington around 1890.

In other words, Jean’s father’s ancestry suggests Pierre spoke a descendant of Northern Minnesota Ojibwe (or possibly Saulteaux, or a more northern variety of Border Lakes Ojibwe), but Pierre was often absent, and I have no information on Jean’s mother’s ancestry beyond the unenlightening facts that she was mixed-blood or Métis and that her Ojibwe forebears were evidently not from the same area as Pierre’s. Furthermore, Jean grew up in a location with a burgeoning white population but no significant Ojibwe population, and continued to live and work there for much of his adult life, undoubtedly limiting his exposure to native Ojibwe speakers beyond, perhaps, his mother—if she spoke Ojibwe at all—and intermittent time spent around his father, uncles, and other extended family (though see the discussion concerning his wife at the end of the post). His biography alone is thus not a sufficient basis on which to firmly conclude what dialect we should expect Jean Bottineau to have spoken.

The second question is, how fluently did he speak Ojibwe at all? Clearly he was at least reasonably proficient in the language, as indicated not only by this vocabulary but also (presumably) by his interactions with Little Shell and other Turtle Mountain Ojibwes who did not speak English or French.[6] But as we shall see, there are indications that either he was not fully fluent in the language, or that the Ojibwe as spoken by his family, or by some of the Pembina or Turtle Mountain Ojibwes by this time, was already undergoing significant obsolescence, with some considerable simplifications, structural changes, and loss of grammatical categories.

Bottineau Vocabulary: Verbatim and Retranscribed

A table with a verbatim transcription of the actual text of the vocabulary may be downloaded HERE (XLSX format).

I’ve tried to follow as closely as possible the original arrangement in Gatschet’s notebook, including spacing, etc., but for practical reasons I’ve segmented out notes or entries which Gatschet clearly added later (and which occupy the same lines in his notebook as other entries) onto new lines. I preserve Gatschet’s spelling, capitalization, punctuation, underlining, and diacritics. One problem I ran into was how to transcribe his use of acute accents, which in his handwriting vary considerably from being directly over the vowel they apply to, to being very far to the right and clearly separated from the vowel. After vacillating on this for a while, I’ve decided to simply write all instances with the acute directly over the vowel, regardless of exactly where it might appear in the original notebook. The two exceptions are certain words with multiple stacked diacritics, where I’ve had to write the acute separately or it isn’t visible, and cases where the acute was written to the right of a superscript <n>. Gatschet sometimes writes what looks like <ē> instead of <é> or <eˊ>. Whether this is an attempt to record a long vowel instead of a stressed vowel, I’m not sure, since it can look slightly different from his normal macron used with other vowels, and when he uses a macron with other vowels it is virtually always in conjunction with an acute accent. He does use <ē> in at least some of his printed works, and I have transcribed the character which looks like <ē> as <ē> here.

In addition to the verbatim vocabulary, I have created a table in which the data in it is re-presented in a manner which will hopefully help make it much easier to use. This may be downloaded HERE (XLSX format). Each row, or a series of rows, corresponds to a keyword (listed in the leftmost column and ordered alphabetically) which is either directly taken from Gatschet’s glosses; or is a simplification or modernization in order to make searching easier or to avoid using what are now potential slurs; or is a more correct gloss, in cases where Gatschet’s is significantly erroneous. Thus, for example, Gatschet’s “co-itus” is under the keyword SEX, “half breed Indian” is under the keyword MÉTIS, and “my arse” and “posteriors” are under the keyword ANUS. Gatschet’s Ojibwe word or sentence and gloss are then given, followed by the word/sentence respelled into the modern orthography, and a corrected gloss, if Gatschet’s is inaccurate or incomplete. If the original Ojibwe is grammatically incorrect or abnormal in some way, this is indicated in the respelled column with a bracketed asterisk [*] or some variant thereof, and a corrected or more standard equivalent is often provided. Finally, there is a column for and the page number where the word/sentence is found. Some of Gatschet’s entries appear multiple times in this reformatted version, because a sentence is generally listed under they keyword corresponding to each significant word composing it.

In the retranscribed vocabulary I have removed extraneous punctuation, spaces, etc., written out some abbreviations in full, and otherwise slightly condensed and modified some parts of Gatschet’s text for ease of presentation and consistency, as well as silently corrected misspelled English words. Thus it must be emphasized the Gatschet column is not always a completely verbatim record of what he wrote—for that, you must consult the verbatim vocabulary, using the page number references in the retranscribed table.

Uncertain readings are marked with question marks, and segments which I have not been able to interpret (even in cases when their phonemic interpretation is fairly secure) are enclosed in ⟨ shallow angled brackets ⟩ and kept in Gatschet’s original spelling. Finally, I have provided English translations for the few items glossed in French.

The rewritten vocabulary additionally contains a number of detailed notes on specific forms, to the right of the final main column—generally words that deviate in some way from what is expected or pose some difficulty in interpretation. Because they are repeatedly referenced both in this post and in two supplementary documents, these notes are also available on a separate page on this site HERE.

Notational Conventions

In addition, I’ve used the following conventions (both in the tables and in this post):

- gray text = material apparently added later by Gatschet, either in pencil and/or seemingly using a different pen.

strikethrough= characters struck through by Gatschet. Since in this font struck-through <e> is almost impossible to distinguish from regular <e>, I write struck-through <e> as <ɇ>. Note also that all instances of <i> are struck-through <i>’s, not a barred i <ɨ>, and that <´> represents an instance where Gatschet originally wrote a vowel with an acute accent but then crossed the accent out.- \inward-pointing slashes/ or ^carets^ = enclose material later inserted by Gatschet into the word or line and written above or below the word/line it is inserted into.

- X = illegible character.

- {?} = follows a word when I’m uncertain of the reading of some or all of it.

- {i} = (in the rewritten table) an initial epenthetic /i-/ which Bottineau pronounced in some cases to avoid illegal consonant clusters when giving Gatschet just the stem of an inalienably possessed noun rather than a possessed form, and not actually present in the Ojibwe stem.

- One thing I have not indicated is cases where Gatschet originally wrote one or more characters and then over-wrote them with new characters as a correction (as opposed to crossing the old characters out and then inserting new ones), partly because it’s frequently difficult or impossible to tell what the original reading was.

In the rewritten table, ungrammatical or incomplete Ojibwe words or phrases/sentences are marked with a preceding bracketed asterisk [*], and usually a grammatically correct alternative is provided within [square brackets]. Merely unidiomatic phrases are usually left as is, and are addressed in the discussion below instead. Uncertain readings are marked with question marks, and segments which I have not been able to interpret (even in cases when their phonemic interpretation is fairly secure) are enclosed in ⟨ shallow angled brackets ⟩ and kept in Gatschet’s original spelling.

In many cases Gatschet provided plural forms for nouns, and occasionally for verbs. For reasons of space, in the modern Ojibwe column of the rewritten table I have only listed the plural suffix separately, and not, as Gatschet usually did, provided the entire plural form of the word. For example, where Gatschet wrote “kgakígan , pl. kakíganan” for “male chest,” the modern Ojibwe column has -kaakigan +an. If Gatschet’s singular and plural forms differ only in the presence of the plural suffix, I also use the same convention in the “Gatschet” column (e.g., for “egg,” instead of “wáwan, pl. wáwanan”: “wáwan +an”); however, if he wrote the singular form of the stem differently from the plural form, I have kept both written out fully (e.g., for “fox”: “wágush, pl. wagúshag”). There are some cases—discussed below—where the Ojibwe form appears to contain multiple plural suffixes; in these cases the main one is set off with a plus sign and any remaining ones with a hyphen. I have not marked the few cases where Bottineau used a plural suffix that is incorrect for that noun stem; these are again listed and discussed below. In the few instances where Gatschet gave a “plural” verb form, I’ve treated that as a separate entry.

Finally, there is inconsistency in how Bottineau pronounced and Gatschet wrote the first person prefix ni- (and a few other words with an initial ni- sequence) when preceding lenis plosives. In many Ojibwe dialects, an excrescent nasal is inserted between the vowel and plosive or obstruent (e.g., ni + dagoshin → nindagoshin “I arrive,” ni + bi-izhaa → nimbi-izhaa “I come”), and in a few, particularly Southwestern Ojibwe, there is instead metathesis, with ni- showing up usually as iN- (e.g., indagoshin, imbi-izhaa). While speaking slowly and carefully, Bottineau evidently usually did not produce any excrescent nasal, at least that Gatschet could hear, while at other times he did. In a few instances just the nasal consonant is written (<nbagátomen> “we boil it” and <ndoshitómen> “we make it”), which likely reflect somewhat more allegro speech in which the ni(N)- sequence is pronounced as a syllabic nasal. For consistency, in the modern Ojibwe column I’ve transcribed all of these as niNC-, but you can easily see from the Gatschet column how that particular word was originally transcribed.

Bottineau Vocabulary: Commentary

While I’ve tried to make it so that it shouldn’t be necessary to consult the vocabulary in order to follow the commentary here, it may still be useful to have it open in another window when doing so.

Gatschet’s Field Methods

(Some potential issues regarding the reliability of Gatschet’s records will be addressed below.)

Gatschet did his fieldwork with speakers just as linguists today do: either by going to them, or taking down information from consultants who were already close to him. In his case this mostly meant, as Mooney wrote (1907:563), “systematic[ally] interviewing night after night . . . the numerous Indian delegates visiting Washington [where Gatschet’s office at the BAE was located] during Congressional sessions.” While Bottineau did travel to Washington frequently in his later years, the information Gatschet provides at the top of the first page of the vocabulary indicates that this may not have been the case here, and his session with Bottineau took place in Minneapolis. (It may be recalled that in 1878 Gatschet was not yet an employee of the BAE, but rather was an ethnologist with the Geological and Geographical Survey, though he was still based in Washington.)

Organizational Plan and Digressions

It’s quite clear from the order and organization of the material that before beginning, Gatschet had a specific plan in mind of at least the general categories and outline of the vocabulary and information which he wished to gather—one almost identical, in the beginning, to the outline he followed in collecting the shorter Potawatomi vocabulary which appears in the same notebook. To some extent the outline follows that laid out by J. W. Powell, his superior at the Survey, in Powell (1877), most obviously in beginning with names for humans and life stages, and in some of the specific vocabulary words to collect (e.g., words related to political organization and government, including “war chief,” “council member,” and “slave”). Indeed, it’s quite clear that Gatschet was directly following Powell’s schedules in at least some instances. For example, to again use Powell’s schedule V (“Governmental Organization,” pp. 26-27), on two successive lines, Powell lists “Council” and “Council chamber (sometimes built under ground, and called sweat-house).” Meanwhile, on pg. 57 of our vocabulary, Gatschet elicited “councilmen,” then (after a few digressions based on the response Bottineau gave him) “council-house,” followed by a brief ethnological note on “steam – sweat'g” practices, despite the fact that sweatlodges have no special connection to council meetings in Ojibwe culture or language, so his questioning Bottineau on sweatlodges at this point can only have been because of Powell’s note that some tribes held council meetings in “sweat-houses.”

Nonetheless, generally speaking, while Gatschet followed Powell’s outline to some degree, he failed to elicit a great deal of the vocabulary and grammatical information (e.g., kinship terms, colors, traditional implements and tools, etc.), and the order in which he elicited various categories frequently differed from Powell’s order. The vocabulary begins with words relating to humans and life stages (pg. 23), moves to a few animals (25) followed by names of various metals (25-27), names of some racial/ethnic groups and tribes (27-29), placenames (29-31), body parts and bodily functions (33-39), various significant Ojibwe “tribes and localities” (in English) (40), numerals (43), and a few words on bad weather (45). At this point the words become a bit more semantically disorganized until page 51, dealing with peoples’ health and condition, then terms related to life and death (53), eating, drinking, and food (53-57), a few words pertaining to traditional Ojibwe political organization and the like (57-59), a list of the Pembina Band’s clans/doodems (59), a short list related to seasons and times of the year (61), and finally terms related to religion and traditional sacred stories (63-65). The contents of pages 41 and 49, and a few terms scattered elsewhere (e.g., between pp. 31-33) are a bit more disorganized, though still often broken up into categories (e.g., the four cardinal directions at the beginning of pg. 41, and various times of the day at the bottom of the page). Gatschet also clearly attempted to elicit some grammatical material, though he did not spend much space or energy on this: inalienable possession or possibly just possession on page 33, imperatives and verb tenses on pp. 45 and 49, and relative time reference or tenses on pp. 45-47; his label at the top of page 49 also makes explicit that he is investigating distributive plurals there.

While Gatschet thus clearly had a general plan in mind before beginning the elicitation session, one can catch glimpses where an answer by Bottineau caused him to deviate for a moment to explore that answer further. For example, in the section where various metals are listed, “iron” is given as “ashkî́kuman” (ashkikomaan, pg. 25), with Gatschet then writing on the immediately following line: “raw, soft metal, which can be cut.” This must by a gloss supplied by Bottineau (cf. ashk- “raw, fresh” and -komaan “knife,” though Bottineau’s gloss is a folk etymology). The next entry, in the middle of what is otherwise a list of metals, is for “it is soft.” This makes sense only if Gatschet, on being told by Bottineau that ashkikomaan literally meant “raw, soft metal, which can be cut,” asked him something like, “So how do you just say ‘soft’?” In fact, several of the other metal entries show evidence of the same thing: “copper” (glossed, due to Bottineau’s input, as “yellow metal”) is followed immediately by “yellow”; “silver” [the metal] (waabishki-zhooniyaa, in Bottineau’s terms meaning “white valuable,” though not glossed by Gatschet) is followed immediately by “white.” Similarly, on page 33, after eliciting three terms relating to cats (“lynx, catamount,” “cat,” and “tabby” [actually “female cat,” but mistranslated]), the next term Gatschet records is “gourmand” (i.e., “glutton”), because the word for “cat” literally means “little glutton” (glossed by Bottineau and hence Gatschet as “le petit gourmand”).

Another probable example is found on page 29, where “prairie” (“máskude” = mashkode) is immediately followed by “fire” (“ishkudé” = ishkode); the two words have no close semantic connection, but of course sound almost identical in Ojibwe, and Bottineau likely offered the word for “fire” after giving the one for “prairie” because the nearly homophonous mashkode brought it to mind.[7]

Of course, many of the religious and cultural terms would have been supplied by Bottineau on the basis of a general prompt or question by Gatschet. The most interesting example of this, in my opinion, is on page 53. After a number of words relating to birth and life, Gatschet began a line with “funeral”—but then crossed this out. The lines following this are the terms: “to put a corpse away (to keep from destruction)”, “to hang (a corpse.) (viz. put on scaffold)(elevated place),” “we have put him away,” etc. Obviously, Gatschet asked Bottineau for the Ojibwe term for “funeral,” but Bottineau replied with an explanation of the old Ojibwe mortuary practice of placing the wrapped body in a tree or on an elevated scaffold, and Gatschet dutifully recorded the terms relating to this custom instead. Another likely example is found on page 63, in the midst of a number of terms relating to Ojibwe traditional religious practitioners and shamans. After several terms relating to the Midewiwin, and just before “rattle (of the conjurer)” on the following page, is the seemingly unrelated entry “cords tied.” I suspect, however, that this is a reference to the jiisakiiwin or Shaking Tent divination practice, which often included a portion in which the shaman was bound with cords or ropes and placed inside the tent, in some cases then being miraculously being freed of these shackles by his manitou helpers. It seems likely that Bottineau made some mention of this to Gatschet while they were discussing Ojibwe shamanism, and Gatschet thus recorded the term for cords being tied—although it’s a bit odd that no other terms related to the jiisakiiwin ceremony or its practitioners are given.

Some of Gatschet’s plan/organization makes sense only under the assumption that he was already familiar with certain facts or concepts. The most obvious example of this is on page 29, where Gatschet elicited the Ojibwe name for the city of Chicago, before then recording several words related to skunks and onions. Now, the toponym “Chicago” is in fact from an Algonquian word referring to the wild garlic/ramp Allium tricoccum (also known as “wild onion”), which in turn is a word that literally means “striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis)” or “skunk plant” (it emits a skunk-like smell when crushed). While the outline of this etymology has been known for a very long time, there has been uncertainty over the donor language, and for many years many people believed it meant “skunk place” (e.g., cf. Ojibwe zhigaagong “skunk place”) rather than “wild garlic [= skunk (plant)] place”; it’s still cited as meaning “skunk place” (or an incorrect plant like “skunk cabbage place”) in a number of sources.[8] In any event, Gatschet was evidently interested in this question, and so asked Bottineau for terms relevant to it. This line of inquiry was definitely initiated by Gatschet himself, and not based on a suggestion by Bottineau: not only is the first entry for “Chicago city,” rather than for “skunk” or “onion” or similar (in a context where no other placenames are being elicited), but he elicited the exact same sequence of words in the Potawatomi vocabulary he collected in the same notebook at roughly the same time (pg. 28).

Use of Other Sources

We can also note that Gatschet made use of several other sources in addition to Bottineau in compiling the vocabulary, although sparingly, and all but three of the Ojibwe words in the main entries were supplied by Bottineau. Gatschet explicitly mentions at least four other sources by name: Lahontan (= Louis-Armand de Lom d’Arce, Baron de Lahontan) on page 31 as the source of the term “Mitigouche” meaning “shipbuilders” in Algonquin (in his lexicon Lahontan in fact spells this <Mittigouch> [Lahontan 1728:227, 1905:738]); Steinthal (= Heymann/Hermann Steinthal) on pp. 47 and 51, both referencing page 562 in one of Steinthal’s works, although I haven’t been able to figure out which one; “Longf.”/Longfellow (= Henry Wadsworth Longfellow) on page 65 as having “nokómis” for “my grandmother” (in the original The Song of Hiawatha this is spelled “Nokomis,” with no accent, though metrically it must be stressed on the second syllable in the poem) and having the word for “squirrel” also reflected in Hiawatha (Gatschet recorded it from Bottineau as “adshitáma”; it appears in Hiawatha as “Adjidaumo”); and two words/names (the top one apparently “surveilleur,” the bottom one illegible and possibly crossed out; see the appendix below), also on page 65, cited for the claim that the name/figure “Hiawatha” is not Ojibwe and that the original (Iroquoian) name was <ayawáta> (cf. Onondaga Hayę́hwàtha’, Mohawk Aionhwátha’ [Tooker 1978:424]).

There are at least three additional locations in which Gatschet quotes a word from another source, but does not cite the source(s), so I’m not sure what they are. These can partly be identified by: in one case being a citation from a language other than Ojibwe; the presence of <l>, which no longer existed as a phoneme in Ojibwe in the late 1800s; the use of the old French character <ȣ>, which Gatschet makes no other use of in this vocabulary though he used it in some of his other fieldnotes; and other spelling conventions which are otherwise completely unlike those Gatschet employs. These uncited quotations are: (1) “apéȣ” cited as the Cree term for “man”/“male,” page 33, on the line where the English keyword/phrase is “Lenni Lenape” (which literally means “regular regular-man”; presumably Gatschet was drawing a connection between Lenape and supposed Cree “apéȣ,” although as in Delaware, -āpēw in Cree only appears as a Final, not a free word); (2) “wah-say-ya” given as one word for “to shine” on pg. 41 (not only is the spelling and division into syllables completely foreign to Gatschet and other professional American linguists of the time [though entirely in line with typical transcriptions of Indian languages by non-linguists and by some earlier anthropologists], but the word is crammed in above the line with what appears to be a different pen than the one used to write the original Ojibwe entry on the line); and (3) “Ah.nung” for “star” on the previous line, also in a foreign transcription system and written with a different pen (and sharing the line with the original entry, <ánung>). The word “kílio,” listed along with vague English and French definitions of <kînî́u , kînî́u> (= giniw, which means “golden eagle, Aquila chrysaetos”) on page 59, may also be something Gatschet took from another source, but this is less likely, as discussed later.

Transcription System

Finally, before moving on to the content of the vocabulary, beginning with the phonology represented, I will close this section by listing my best guesses as to what the orthography used by Gatschet is intended to represent phonetically—which will to some extent beg some of the questions of the following discussion on phonology, but I hope the evidence I present is strong enough to bear out my guesses/assumptions here. Keep in mind too that these are what Gatschet heard and/or wrote, not necessarily what was pronounced. Unfortunately, in some areas Gatschet does not seem to have been an especially skilled phonetician or have had a great ear for other languages, especially at this stage of his career, and this is compounded by the fact that he was not using a very specialized phonetic alphabet here, instead simply employing the Latin alphabet as used in familiar Western European languages with a handful of deviations in line with other Americanists of the time. (In 1878 the phonetic alphabet recommended by Powell and William Whitney [Powell 1877]—which had a number of similarities but also some differences with Gatschet’s transcriptions—was quite similar to the Western European Latin alphabet as compared with later Americanist phonetic alphabets, including Powell’s own substantial revision of 1880 [Powell 1880]. It seems, however, as though Gatschet continued to use his original transcription practices largely unchanged throughout his career.)

In spite of these drawbacks, interpreting Gatschet’s consonant symbols is mostly fairly straightforward, though some phonetic details were likely not indicated: <p, t, k, tch, b, d, g, ds(h), m, n, w, y> = [p, t, k, tʃ, b, d, ɡ, dʒ, m, n, w, j]. <ss> = [s], <s> = both [z] and [s], <sh> = both [ʃ] and [ʒ]. <’h> or <χ> preceding a plosive represent [ʰ]/preaspiration. <ng> probably represents the cluster [ŋɡ] while superscript <ng> (and <ng>?) represents [ŋ] (and in a couple cases, what was probably a nasalized transition between two vowels, perhaps [ɰ̃], and sometimes [j̃]). <ñ>—and in a few cases <ni> or <ni> or <ny>—represent what Gatschet may have heard as [ɲ] or [ɲj] but which were almost certainly pronounced [j̃]. <-> indicates the hiatus Gatschet heard for [ʔ] (except in a couple instances, “boy” and “flesh, meat,” where it indicates a hiatus he heard which was not [ʔ]). [w] (and also [wV] and [Vw] on occasion) is also sometimes written as <u> (almost universally so after a consonant, though a few instances of post-consonantal <u> and <w> are also found), and [ij] as <i>.

Vowels are more difficult to interpret—and some additional details on my assumptions as to what Gatschet’s characters likely symbolized will be given in the discussion on phonology below—but I assume that <i, u, e, o, a> = [i, u, e~ɛ, o, a(~ɑ~ʌ)] (both phonetically short and long), <î, û> = [ɪ, ʊ] (both phonetically short and long), and <ä> = [æ] (both phonetically long and short). An acute marks stress, a macron explicitly marks a long vowel, and a breve a short one.[9] <n> following a vowel indicates nasalization.

The assumption that <î> and <û> represent laxed/lowered vowels requires some justification, especially since, according to Costa (1991a:36), at least in his Miami-Illinois fieldwork from 1895-1902, Gatschet used a circumflex to mark long vowels. This was, however, nearly two decades after he took down the Bottineau vocabulary, and his transcription practices could easily have changed in the interim; he also uses circumflexes overwhelmingly more frequently in the Bottineau vocabulary—on pretty much every other word—than he apparently did in his Miami-Illinois records, where the citations I’ve seen from Costa’s publications indicate that he used them extremely sparingly. In our vocabulary he very, very frequently marks short vowels with circumflexes (as will be noted below, my impression is circumflexes are used on short vowels significantly more often than on long vowels, though I have not attempted to actually count this). And if the circumflexes are not marking length, and very commonly occur on short vowels, then most likely they’re marking a quality difference from plain <i> and <u> (it’s unlikely they are solely marking vowels as being short, because as noted Gatschet also makes some limited use of macrons and breves, and as will be seen below these quite consistently correspond to long and short vowels). Furthermore, in his published Klamath-Modoc grammar, Gatschet uses circumflexes to mark what he calls “deep” vowels (<î û â>), as opposed to “clear” ones, and his descriptions of the distinction and his examples make it clear that <î>, <û>, <â> represent [ɪ], [ʌ]/[ʊ], and [ɔ] respectively, and other symbols the more peripheral vowels [i], [u], [a], [e], etc. (Gatschet 1890a:207, 212-214; this is mostly in line with Powell’s phonetic alphabets). And there are additional examples of Gatschet using such a transcription system, e.g., a brief comment by Haas (1963:65) indicates that he used <û> to transcribe [ʊ] in notes of Chickasaw from 1889.

Phonology

Although there are some uncertainties, the material recorded here does permit us to learn a decent amount about the phonology of Ojibwe as spoken by Bottineau. Two broad questions to ask up front are: (1) was there any quality difference between long and short vowels, or just a quantity difference?, and (2) what was the phonetic nature of the distinction between “lenis” and “fortis” obstruents?

Regarding the first question, there are some difficulties, because although in this vocabulary Gatschet occasionally marked vowels as long, he rarely did so, and given other issues with Bottineau’s Ojibwe, including issues relating to stress, this raises the question of whether he even had distinctively long vowels, so this bears further investigation.

By my count, Gatschet marks a vowel with a macron 37 (or possibly 38) times; of these, only three fall on expected short vowels (“he, she has an offspring” [pg. 23], “he is resting” [pg. 29], and one instance of the plural of “young dog” [pg. 31]), as well as one case in which the analysis of the word is uncertain and so the vowel length cannot be stated with complete confidence (at least by me: “he is now in the act of medium,” pg. 63—see Note P). In the remaining 33 or 34 cases (92% of the total, when throwing out “he is now in the act of medium”), the macron accurately marks an expected long vowel. Furthermore, although I have not done any sort of quantitative analysis of this, in those cases where Gatschet’s marking of stress diverges from one of the usual patterns (discussed in more detail below), the vowel he marks as stressed is very frequently an expected long vowel. Finally, while there are not many minimal pairs (of any sort) in Ojibwe, there are actually several cases of minimal or near minimal pairs in which the two words/morphemes are not only distinguished (solely or partly) by vowel length, but are semantically or paradigmatically related as part of the same “set,” making the difference in vowel length between them especially salient, most notably: the numerals niizhwaaswi “seven” and nishwaaswi “eight” (repetition forms for Bottineau: niizhwaasing “seven times” and nishwaasing “eight times”), and the conjunct verbal endings -(y)aan “1sg” and -(y)an “2sg” (as well as other verbal endings, but these two examples are sufficient). If there is one place someone is going to explicitly mark vowel length, it is in these pairs, especially the verbal suffixes.[10] And in both of these crucial cases, Gatschet does explicitly mark vowel length, although only partially in the case of the numerals: <nī́shwassing> [“seven times”] vs. <nîshuássing> [“eight times”] (both pg. 43); and <tchibuá tagushini/ā́n> “before I arrive” (jibwaa-dagoshiniyaan, pg. 45) vs. <tchibuá tagushiniắn> “before you arrive” (jibwaa-dagoshiniyan, pg. 47).

Taken together, these data add up to very strong evidence that Bottineau did distinguish vowel length, and that Gatschet merely failed to record it in most instances. This is consistent with what I know about his fieldwork on other languages, where he occasionally heard vowel length, but usually did not.

With that out of the way, we can consider the original question, which was whether Bottineau’s Ojibwe had a quality distinction between vowels in addition to a quantity distinction. In modern Ojibwe, this is extremely common, almost universal; long vowels are relatively tense, while short vowels are most often pronounced laxer and more centralized (with /a, i, o/ realized as something like [ʌ, ɪ, ʊ], though with plenty of variation), and especially so when unstressed. Many individual varieties have further short vowel laxing/centralization rules—for instance, some dialects of Algonquin merge /a, i/ to a lax [ᵻ].

However, it doesn’t seem as though if this was always true, at least in all areas. Many older grammars and dictionaries, such as those of Frederic Baraga—not to mention the works of the French missionaries in the 17th and 18th centuries—fail to note any quality difference between long and short vowels. Baraga had a good ear for the language in general, was a native speaker of Slovene, and also spoke German from a very young age—he even wrote almost all of his personal diary (Baraga 1990) in German—and so should be expected to have heard a difference between, say, [iː] and [ɪ] or between [a] and [ə].[11] Jean-André Cuoq similarly doesn’t really mention any significant pronunciation variants in vowels, although he discusses pronunciation less than Baraga does. The “general English/continental Europeanish”- and French-based orthographies Baraga and Cuoq were using were ill-suited to mark such distinctions in any case. As late as 1911, the Dutch linguist and anthropologist J. P. B. de Josselin de Jong, describing the speech of multiple individuals from Red Lake, MN (where Bottineau’s paternal ancestors were from, and not far from the Pembina region and the area where Bottineau’s paternal grandmother was born), doesn’t appear to distinguish significant vowel quality differences in certain cases. In particular, for both /i/ and /iː/ he only writes <i>, describing it as “about = engl. ea in meat; sometimes a little longer like ee in meet” (??), and also says that the /a/-quality vowels are “never [pronounced] like u in engl. but” (Josselin de Jong 1913:v). Josselin de Jong was a native speaker of Dutch, so he would certainly be expected to be able to hear a difference between [i(ː)], and [ɪ]. (Then again, Gatschet frequently missed, or at least failed to indicate in his transcription, oppositions which existed in his native dialect of Highest Alemannic.)

On the other hand, other contemporary sources do indicate or suggest laxing of short vowels in several different varieties of Ojibwe, including at Red Lake and elsewhere in northern Minnesota, not to mention the hints of lax vowels in the French spellings dating back to the 17th century mentioned in footnote 11. The grammar and dictionary of the missionary Edward Wilson, published in 1874, certainly seem to indicate that the Ojibwe speakers he was working with (mostly of Eastern Ojibwe) had laxed short vowels; here his English-based orthography is actually quite helpful in revealing this (cf., e.g., <opineeg> “potatoes,” <muhkuhk> “a box,” <cheemaun> “a canoe,” and <neebing> “in summer” = opiniig, makak, jiimaan, niibing [Wilson 1874:11]). The detailed phonetic (pre-phonemic) orthography used by William Jones (1917, 1919) to transcribe Ojibwe texts from northern Minnesota and the north shore of Lake Superior from 1903-1905 also makes clear that the speakers he was working with often, though not consistently, had quality as well as quantity distinctions on vowels, and Jones, in addition to being a native speaker of both English and another Algonquian language (Meskwaki), was by far the most linguistically sophisticated recorder of Ojibwe to that point. And finally, in the orthography of Wright (n.d.) (ca. 1890), a missionary who learned Ojibwe at Red Lake and Leech Lake, MN in the mid-1800s and was primarily describing the speech of Red Lake, short /a/ is fairly often spelled <û> (or occasionally <u> or <ĕ>, and some other vowels are also occasionally spelled as though laxed) (e.g., <Û-kû-kûn-djĭ sû-kû-teg> for “Living coals” = akakanzhe zakideg “burning coal” [Wright n.d.:9]; <Nij-tĕn-û û-cĭ be-jĭk> “21” = niizhtana ashi-bezhig [ibid., pg. 17]).

So, at the very least by the time Gatschet took down this vocabulary, some Ojibwe speakers had a quality distinction between their long and short vowels, including some but perhaps not all of those near to people Bottineau had family connections with. Which of these groups Bottineau was a part of is a bit difficult to determine, at least not without a lot more work that I haven’t had time for. Gatschet not infrequently writes long /iː/ and /oː/ with <î> and <û>, but very often these have added acute accents even when the word or stem is monosyllabic (e.g., <nî́nsh> “hand, finger” = -niinj [pg. 37]; <mû́> “excrement” = moo [pg. 39]; <wî́giwan> “home, residence” = wiigiwaam [pg. 41]; <nî́sh> “2” = niizh [pg. 43]; <nabû́b> “soup, broth” = naboob [pg. 55]; etc.). However, <î> and <û> are also used for short /i, o/, seemingly a reasonable amount more frequently, though I have not actually counted this up (e.g., <û́kan> “bone” = okan [pg. 37]; <sî́kuan> “the spittle” = zikowin [pg. 39]; <kísîs> “sun, moon, month” = giizis [pg. 41]; <nî́ssui> “3” = niswi [pg. 43]; <pagísû> “he is bathing” = bagizo [pg. 49]; etc.). Similarly, <i> and <o>/<u> are used for both short and long vowels, as is <a>. As discussed above, I’m not completely positive what Gatschet actually intended to indicate with a circumflex, but it’s almost certainly some difference in vowel quality. My working assumption, as stated previously, is that <î, û> = [ɪ, ʊ] (phonetically short or long), <i, u, o, e, a> = [i, u, o, e~ɛ, a(~ɑ~ʌ)] (phonetically short or long, plus in some cases, before another vowel, <u> also indicating [w] or [Vw] and <i> [ij]), <ä> = [æ] (phonetically long or short), a macron explicitly marks a long vowel, and a breve a short one. Again, however, I have not had the time or patience to actually do an in-depth analysis of this. But my impression is that while there may not be a huge difference in spelling between long and short vowels, there is definitely some, and so Bottineau probably pronounced his short vowels as lax/centralized more often than he did the same for long vowels, even though he apparently pronounced both short and long vowels as both tenser and laxer at times. If anyone else wants to do a more thorough analysis, have at it.[12]

The second basic question asked at the beginning of this section was what the nature of the distinction between “lenis” and “fortis” obstruents was in Bottineau’s speech. This is a parameter of pronunciation which varies considerably among different Ojibwe-speaking communities and among individual speakers, though lenis consonants, nowadays, are almost always voiced intervocalically and always voiced after nasals, and fortis consonants are always voiceless, usually longer in duration than lenis ones, frequently preaspirated or postaspirated, and seem to be produced with greater muscular tension. Historically the fortis consonants were preaspirated, which is how they are still pronounced in Oji-Cree, many Western Saulteaux communities, and many Northwestern Ojibwe communities. In a very small number of cases, Gatschet in fact explicitly writes a fortis stop as preaspirated, usually indicated by a preceding <’h>. These cases (ignoring plurals of the same words) are:

- <á’hkî wä́nsi> “old man” = akiwenzii, pg. 23 (also with <ắki> indicated as an alternative pronunciation for the initial portion).

- í’hkuä “woman” = ikwe, pg. 23 (also derivatives of this such as <ushkí i’hkuä> “young woman” = oshki-ikwe [pg. 23], <wisákude wi’hkué> “half breed woman” = Wiisaakodewikwe [pg. 27], and <i’hkue gáshagäns> “tabby” [actually “female cat”] = ikwe-gaazhagens [pg. 33]—but not consistently, cf. <ikuésäns> “little girl” = ikwezens [pg. 23]).

- <u’hpuágan> “tobacco pipe” = opwaagan, pg. 31 (also derivatives of this on the same page, except for the plurals for “wooden pipe,” <mî́tig upuáganag> and <[mî́tig] upuáganan>).

- <uχgā́d> “leg” = okaad, pg. 35.

- <û’htáwag> “ear” = otawag, pg. 37.

- <u’hpî́kuan> “back” = opikwan, pg. 37 (but not an [ungrammatical] derivative of this on the same page, <upíkuan û́kan> “backbone, dorsal spine”).

- <ú’hkan> “bone” = okan, pg. 37 (also spelled <û́kan> in the same entry; also see above on <upíkuan û́kan>).

- <á’htis> “sinew, ligament” = atis, pg. 37.

- <kí’htchi> “hard [i.e., ‘a great amount, very much’]” = gichi-, pg. 45 (given as an alternative spelling/pronunciation of <gitchî́>).

- <animî́ki=’ka> “[it thunders]” = animikiikaa, pg. 45 (part of the same entry as “hard” above; I’m not positive whether this is actually meant to indicate preaspiration on the final /kː/).

- <a’htawesse> “[the fire is/has] going/gone out” = aatawese, two entries on pg. 45 (also spelled <atawésse> and <átawése> once each on the same page).

- <pí’htchibúen> “poison” = bichibowin, pg. 55 (also spelled <pitchipúen> in the same entry, and related terms spelled <pitchibû́>, etc., on the same page)

The initial takeaway from this is that Bottineau very occasionally pronounced fortis plosives as preaspirated, but usually did not. Costa (1991a:36, 1991b:366) states that Gatschet had some trouble hearing preaspiration in Miami-Illinois, but was often able to record it; in the latter article Costa says he “heard [it] more often than not.” Costa (2003:22) states that “he did not always hear preaspiration,” which is still consistent with the preceding claims. The citations I’ve seen suggest that for Miami-Illinois he wrote it reasonably frequently, and even heard it on fricatives with some regularity. This fits with what LeSourd (2021:195) describes for Gatschet’s work on Passamaquoddy in the 1890s, where he “recorded most, though not all, preconsonantal occurrences of h” while “[o]ther early recorders of the language typically missed preaspiration.” The accompanying Passamaquoddy text taken down by Gatschet shows that this included him fairly regularly recording preaspiration even on fricatives. All this is suggestive that the almost total lack of preaspiration marking in the Bottineau vocabulary genuinely reflects Bottineau fairly rarely pronouncing fortis consonants with preaspiration, though there were undoubtedly some instances in which he did so and Gatschet failed to hear it.

There are two points to note in this regard, however. First, Gatschet collected the Bottineau vocabulary in 1878, at the start of his career with American Indian languages and over a decade before he began work on Passamauoddy and Miami-Illinois. In the intervening period, he may simply have become better at hearing this distinction, even if his abilities were still imperfect. (In fact I would be very surprised if this were not the case given the tremendous amount of additional exposure to Indian languages he had over that time, including several Algonquian ones.) Second, observe that the distribution of the preaspiration marking in the Bottineau vocabulary is not random: (1) it occurs unusually frequently on body part terms (I don’t have any idea why this would be the case, other than observing that in all but one case the preaspirated fortis stop follows the third person prefix o-, which Gatschet’s transcription indicates was [u] or [ʊ] in these particular instances, and the other case [“sinew”] also involves a fortis stop that immediately follows a word-initial short vowel—as do three of the other, non-body part examples, for that matter), and (2) it becomes significantly less common the further into the vocabulary Gatschet gets. The first page has three words marked with preaspiration, and the first 12 pages, ignoring page 40, which only has one Ojibwe word, contain all but one of the examples in the vocabulary; there is only one word marked with preaspiration over the final ten pages (on page 55). The most likely conclusion, in my view, is that by the mid-point of the vocabulary, and probably before then, Gatschet had realized that preaspiration was redundant/non-distinctive, and so failed to continue recording it in the cases when he successfully heard it from that point on. It may also be relevant that the one word which Gatschet marks with preaspiration late into the vocabulary is one in which the preaspiration occurs on /tʃː/ following /i/: bichibowin = <pí’htchibúen>. William Jones’s text collection indicates that at least for his consultants preaspiration was very salient in just this environment, apparently with the /h/ commonly assimilated in place to the /i/ and /tʃ/ as something like [stʃ] or [çtʃ] or [ʃtʃ]. Thus, e.g., Jones often spells gichi- as <kistci> or similar and izhichige as <ijictcigä> or similar.

If Bottineau sometimes pronounced fortis stops with preaspiration but frequently did not—a situation still found among a number of Ojibwe speakers—he likely distinguished the lenis/fortis pairs primarily on the basis of both length and (optional) voicing. If he did use consonant length, however, Gatschet never records it;[13] unfortunately, it is impossible to say whether this is due to Bottineau genuinely not pronouncing fortis consonants longer than lenis ones, or just Gatschet being unable to hear, or electing not to indicate, consonant length. (While I have not closely examined all of the publicly available material he collected on Ojibwe, in what I’ve gone through so far I’ve found no indication of consonant length there either, which strongly suggests Gatschet was unable to hear or indicate in writing consonant length in general—though it’s important to keep in mind that this does not conversely mean that Bottineau was producing it.) As for voicing, the lenis consonants are variably recorded with either voiced or voiceless symbols intervocalically, but usually are written as voiced, and always as voiced after nasals (except for the fricatives, which are never written as voiced, as pointed out in footnote 13); they are also fairly often written as voiced word-initially, but word-finally they seem to more often be written as voiceless—though there are still a good number of voiced examples—except that the animate plural suffix is consistently written with final <g>. This suggests a not-unexpected situation given Bottineau’s time and place: lenis consonants are always voiced after nasals and usually but not universally voiced intervocalically, are variably voiced initially, and are sometimes but not frequently voiced finally.[14] Gatschet’s recording of the animate plural suffix as ending in <g> in all cases—except once on the first page—surely reflects his quick recognition of its status as a distinctive morpheme, and thus one that he ended up spelling in a consistent way regardless of precisely how he may have heard it in individual instances. He used a similar practice in several other cases.

In a very small number of cases, fortis consonants are written as voiced, possibly due to mishearing (or possibly not being pronounced as long in those instances: see footnote 13), although two actually feature the same morpheme, e.g.: <piwábig> “iron” (biiwaabik, pg. 25), <wassḗtchiganábig> “glass of window” (waasechiganaabik, pg. 57), <kashkibî́deng> “tied” (gashkapide⟨ng⟩, pg. 63) and <odshidshā́k> “spirit of dead” (ojichaag, pg. 63); for the first two, compare other terms on pp. 25-27 with the same morpheme spelled with voiceless <k> (<osawábik> “copper”; <wábik> “metal”; <piwábikons> [diminutive of “iron”]; <osawábĭ́kons>/<-kons> “cents”; etc.).

Moving on to other phonological issues, one process suggested by Gatschet’s recordings is that Bottineau’s dialect of Ojibwe appears to have had allophonic lowering of /i/ to something like [e] in a number of instances, since they are spelled <e>, or occasionally <ē>. This seems to be most common in two environments. One is word-finally, including preverb/prenoun-finally:

- <unídshanissē> “he, she has an offspring” = oniijaanisi pg. 23 (cf. on the same page <kîdudshánissî> = gidoo[nii]jaanisi with the same final morpheme, although the word is ungrammatical)

- <wemîtígoshē> (?) “French” = Wemitigoozhi, pg. 31

- <ininiwe> “he is a man” = ininiiwi, pg. 33

- <pashkinéyabe> “eyes full of tears” = baashkineyaabi, pg. 39

- <náwe> “middle” = naawi–, pg. 41

- All of the numerals ending in -aaswi are spelled with final <-ā́sswĕ>, <-ássue>, or similar (always with the last character being <e> or <ĕ>), pg. 43

- <óndshe> “because” = onji, pg. 45

- <pā́ssue> “he dries himself” = baaswi, pg. 49 (an alternative pronunciation of baaso, with the common Ojibwe interchange of /o/ and /wi/; cf. <pā́ssu>, <pā́ssû>, and <pássû> on the same page)

- <wabishéshe> “weasel” [actually “marten”] = waabizheshi, pg. 59

- <minupû́gûse> [“taste good”] = minopogozi, pg. 63

- <mámawe> “in a whole, bundle” = maamawi(-), pg. 63

- <mitéwe> “he is now in trance” = midewi, pg. 63

It may be relevant that most of the examples occur either following /w/ (six cases) or a coronal fricative (four cases, plus one instance following the coronal affricate [dʒ]), but given the small sample size it’s hard to be certain.

The other main environment in which lowering of /i/ is indicated is preceding nasal consonants:

- mindimooyenh “old woman,” spelled all four times as beginning with <mindemó…>, pg. 23

- <ndoshitómen> “we are making [it]” = nindoozhitoomin, pg. 27

- <nbagátomen> “we boil [it]” = nimbagaatoomin, pg. 27

- <ishpéming> “high, en haut” = ishpiming, pg. 29

- “resting place” and “he is resting” probably end in -abi (see Note Y) = <eshkanábeng> and <eshkanábē> (the former is pre-nasal consonant, the latter word-final as in the list above), pg. 29

- <sî́kuan> “life” = zikowin, pg. 39 (possibly just a representation of a very lax pronunciation of /i/ as something close to [ə], or an error)

- <tagúsheniang> “[before we] return,” pg. 45 and <tagusheniwát> “[before] they arrive,” pg. 47 = dagoshiniya(a)ng and dagoshiniwaad

- <îshnîkásuen> “name of things (or pronunciation)” = izhinikaazowin, pg. 49

- <pimadî́siwan> “life” = bimaadiziwin, pg. 53 (possibly just a representation of a very lax pronunciation of /i/ as something close to [ə], or an error)

- <tebiwissiniwen> “rassasiement [‘satiety, fullness’]” = debi-wiisiniwin, pg. 55

- Possibly <agómĕn> “to swallow” though the proper interpretation of the ending is unclear (I have assumed it is ⟨a⟩gomind) and the <ĕ> may represent [ə] (see footnote nine), pg. 55

- <pitchipúen>, <pí’htchibúen> “poison” = bichibowin, pg. 55

- possibly <edîtégĕn> “when [they] are ripe” = editegin (though the <ĕ> may represent [ə] (see footnote nine), pg. 61

- <akûsî́wen> “sickness” = aakoziwin, pg. 65

- <bemwḗwē> “sound of thunder travelling over” = bimwewe, pg. 65