Last updated: April 25, 2024

This post will collect and exemplify the most important phonological and morphophonological processes of Proto-Algonquian; it represents a substantial revision and expansion of a section that was originally found in my post on Proto-Algonquian. (For an overall introduction to Proto-Algonquian itself, you can find that post here, and for an introduction to verb inflection specifically, including some of the technical terms used here, see this one. I have not finished revising these to reflect my current beliefs and knowledge or for consistency with this post, though . . . )

While I make no pretense to total comprehensive coverage—which would be nearly impossible—I hope this can prove of use as, at least, the most comprehensive such list available, consolidated in one place and carefully ordered. Virtually none of the given rules are “new,” but to my knowledge they have never been assembled together like this before, exactly—only smaller subsets, often scattered throughout a work, and usually without statements on ordering.

In some cases, of course, there will be alternative ways of formulating the suite of rules to produce the same output. (And of course, as discussed below, different researchers don’t agree on the same rules in the first place.) As just noted, although sometimes the order doesn’t matter to give the correct output, many rules are consciously ordered with respect to one another, and such relationships will be stated explicitly for each relevant rule. Incidentally, note that these are synchronic rules, not an attempt to capture any diachronic order or picture. For example, several of the rules are ordered in a way that clearly does not match the order in which the sound changes responsible must have occurred in pre-Proto-Algonquian, and some others, despite being presented as a single rule, encompass the results and morphologization or lexicalization of what were, historically, multiple different sound changes occurring at quite different times.

Several rules, in particular those involving contraction of vowel-semivowel-vowel sequences (*VGV, i.e. *VwV or *VyV), have yet to be completely worked out for PA. These *VGV contractions specifically are addressed in their own separate section at the end.

There remain a handful of areas in this post which require tweaking or flesh out, but I’m just so exhausted from working on it for months that I’m publishing it as it is now. Sorry. I welcome any comments, discussion, critiques, or alerts to errors.

(And yes, I’m aware these sorts of rules have not been in vogue in linguistics for like three decades, but whatever, I’m not writing up an OT treatment of Proto-Algonquian. I’ll leave that to others. Not the biggest fan of most of OT anyway.)

|

Plan and Layout

I’ll first provide a prose explanation of each change, then a formal notation, followed by one or more examples in both PA and modern languages when possible. In some instances, in the listing of morphemes in the input of a given example I will leave out some morpheme that is irrelevant to the rule at issue, even though it will then show up in the output, but this should hopefully not cause any confusion. In all examples, the input will be given at more or less the deepest possible level, and often intermediate forms, marked with double asterisks, will be provided before the final output in order to help illustrate the processes under discussion or simply to maintain maximum clarity. I’ve made my best effort to have the rules apply in proper order in such intermediate forms, but have not always succeeded (and occasionally have purposely deviated when this interfered with clarity).

In at least a few cases, the cited PA form likely or certainly did not exist as such; all of the phonological and morphophonemic processes such pseudo-PA and equivalent daughter forms are being used to illustrate are valid, however. A few especially uncertain or problematic reconstructions are preceded by a query “?”. Additionally, in some cases one or more daughter forms used in an example don’t reflect a complete, regular descent from the cited PA form, due to various analogies, the requirement to use additional particles to form a grammatical construction, etc.; these are sometimes simply ignored, while in other cases I enclose the non-cognate material in [square brackets].

Notation

In the formal notation of each rule, the abbreviations and symbols below are used. There is also a special morphophoneme |ẅ|, respelled as surface *w.

| / | precedes specification of the environment in which the rule applies |

| __ | position in which the affected segment(s) is/are found |

| # | word boundary |

| + | morpheme boundary |

| ~ | reduplication boundary |

| ≠ | except in the defined environment; OR except for the defined sound or class |

| {a,b,c} | all or any of a, b, and c; a member of the set comprising a, b, and c |

| α | a given value out of a set of possible values |

| Ø | null |

| C | consonant |

| G | semivowel |

| N | nasal consonant |

| V | vowel |

| Vː | long vowel |

| V̆ | short vowel |

| X | any amount of undefined material |

| POA | “place of articulation” |

Terminology and Glossing

For the most part I use the standard repertoire of Algonquianist technical terms and abbreviations—see the end of this section for a few exceptions—and some of these can unfortunately be confusing or opaque to outsiders. Basic introductions to relevant terms, etc., may be found on Will Oxford’s website here and in my posts on Proto-Algonquian (here) and Proto-Algonquian verbs (here); see also a few specific explanations below. For any Algonquianists, note I do depart from standard practice in a few ways. First, I capitalize the terms Initial, Medial, Final, and so one when they are referring to specific portions of the morphology of an Algonquian word, largely to avoid any possible confusion with use of the same terms to describe positions within a word, morpheme, phrase, etc. Second, my glossing practice hews much closer to the Leipzig conventions than traditional Algonquianist practice, especially in the area of person marking, where, for instance, I use “1pl.INCL” where most Algonquianists would use “12.” This sacrifices compactness in order to achieve greater clarity for general linguists. See here for a full list of the glossing abbreviations I employ; for those viewing this page on a computer, all abbreviations can also be moused over to see a pop-up giving the full significance.

A few miscellaneous notes on specifics. As an extremely brief primer on the subject: PA had four major verb classes, depending on the verb’s transitivity and the animacy of its absolutive argument. The names for these classes are of the form “(subject animacy) – transitivity – (object animacy)”:

- Animate Intransitive (AI) verbs = intransitive with an animate subject

- Inanimate Intransitive (II) verbs = intransitive with an inanimate subject

- Transitive Animate (TA) verbs = transitive with an animate object

- Transitive Inanimate (TI) verbs = transitive with an inanimate object

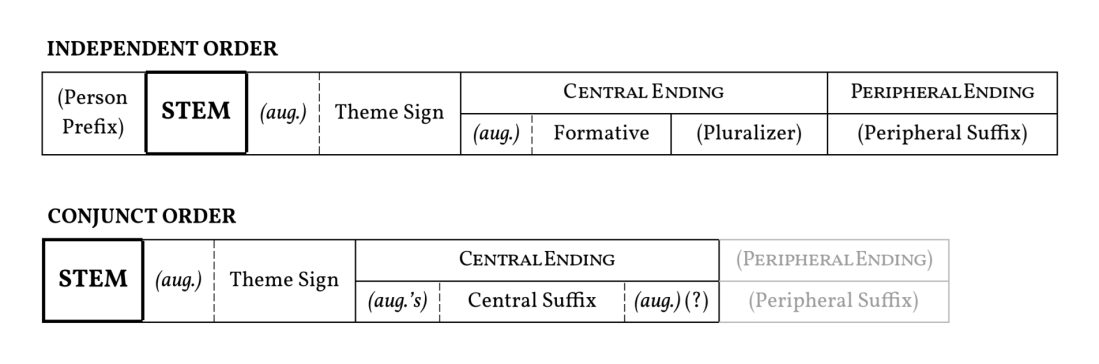

TI verbs can further be divided into three subclasses, here abbreviated TI(1), TI(2), and TI(3). Verbs could be inflected in any of three major inflectional patterns known as orders: the independent, used mainly in main clauses, the conjunct, used prototypically in subordinate clauses and to form participles (but with further complications), and the imperative, used in commands. The basic TA templates for inflectional elements employed in argument-marking were as below; other verb classes were similar, just with some slots absent.

Prefixes, and central and peripheral endings, marked the person, number, and obviation of the subject and object, but (in the independent, and sometimes in the conjunct) did not specify which of the central or peripheral participant was the subject and which was the object. The theme sign accomplished this by either marking the person of the object, or indicating that the verb was inverse. (In TI verbs, the theme sign just vacuously marked that the object was inanimate and its shape defined the subclass of the verb as TI(1) vs. TI(2) vs. TI(3).) In the independent only, there were four formatives, three of them meaningless submorphemic elements, but one still meaningful, and marking certain third persons.

When glossing inflected verbs, parentheses enclose an indefinite object of so-called absolute verbs, e.g., “I see (s.o.)” stands for “I see an indefinite animate object,” such as “I see [a bear],” and so on. With stems containing a relative root, or otherwise licensing a relative root complement, I follow Goddard’s practice of including in the gloss an indication of the general type of complement licensed by the stem, enclosed in {curly braces} (e.g., “to {somewhere},” “{so}, {thus},” etc.)—the intention being that this gloss is a sort of variable, rather than the more specific translation that would be appropriate given full context.

When the gloss of a reflex in a modern language differs substantially from that of the PA example, this will be provided; however, I omit new glosses when the only difference is that: (1) a modern language has lost distinctive absolute verbs, and so a given verb’s object might be definite even though in PA it was indefinite; or (2) a modern language has lost number distinctions in obviative verb inflections, such that, e.g., an obviative object might be singular or plural even though in PA it was only one or the other.

There were two main (and a few minor) slots in PA verbs containing suffixes with tense/aspectual/modal/evidential/mirative and similar meanings. I think there is utility in using distinctive terminology for a couple of the different slots, and do so in some other places, but for our purposes here only one set of suffixes is really relevant and in need of being identified collectively (viz., chiefly *‑pan “emphatic past,” *‑(e)sahan “emphatic present,” and *‑etoke·h “dubitative”). In this post I therefore follow the general Algonquianist practice of calling all of these suffixes mode suffixes (aka “modal suffixes” or “mode signs”); the categories they mark are modes. The precise functions of the various modes in PA are often not known with certainty or not conducive to a single gloss in the absence of further context.[1] As such my translation of them is decidedly approximate, and ultimately not important for this post, which is concerned with formal issues.

One notable distinction made here will be between phonological processes I call contraction and coalescence; these have gone by various different names in the literature, most often both being subsumed under the label “contraction.” See the following footnote for more information and justification.[2]

As a final and more minor note, I refer to the morpheme *‑hk, traditionally called the “prohibitive” following Bloomfield, as a “potential” (cf. Goddard 1979b:102). This, or something like “admonitive,” appears to be a more accurate description of its most neutral function in Proto-Algonquian—essentially, meaning “lest X should happen, maybe X (often undesirable) will happen,” and only functioning as a true prohibitive when combined with some sort of negative or prohibitive particle. Since “potential” is a vaguer label than “admonitive,” I have given it preference.

Sources, Transcription, and Abbreviations

See the following footnote for information on sources. The key works covering PA morphophonology, and providing a great many of the examples used here, are Bloomfield (1946), Pentland (1979, 1999), and Goddard (2001, 2007; also 1979b, 2006), but I’ve drawn on a number of others as well. The footnote also covers constructed examples and how these are indicated.[3]

My transcription of Proto-Algonquian essentially follows Ives Goddard’s post-1994 system, with traditional *ç, *x, and *we (in surface forms) replaced with *r, *s, and *o. I depart in still writing word-initial *e- as such, since I don’t want to fully commit to the interpretation that it was already *i-. (See Rule 23 for discussion.) Proto-Eastern Algonquian is transcribed following the system laid out here and here.

Because of the historical focus of this post, my transcription of Algonquian languages is much closer to a standardized system for equivalent phonemes across all the languages than I normally employ. They are here written with the Algonquianist version of Americanist notation: letters have their approximate IPA values except for ⟨č, š, y⟩ = /tʃ, ʃ, j/ (⟨c⟩ variably marks /tʃ/ or /ts/ = [ts ~ tʃ]), vowel or consonant length is marked with a following raised dot ⟨·⟩, and an apostrophe ⟨’⟩ is sometimes used instead of ⟨ʔ⟩ for /ʔ/. Marking of pitch, stress, voiceless vowels, etc. follows the traditional notations for individual languages, except for Arapaho, and Maliseet-Passamaquoddy pitch distinctions are generally unmarked. I also use an ogonek to mark nasalization. Capital ⟨E⟩, ⟨N⟩, and ⟨S⟩ (and lowercase ⟨æ⟩) represent morphophonemes in the daughters, while capital ⟨L⟩ in PA represents a segment that was either *r or *θ but either we don’t have sufficient testimony to tell which, or it varied between the two. Departures from this system are given in the following footnote.[4]

Citations from languages other than English are italicized, except that for most languages which became extinct or dormant prior to being extensively recorded by modern linguists, phonemicizations are enclosed in ⫽double slashes⫽. (/single slashes/ are reserved for actual phonemic forms transcribed in the IPA.) Phonemicizations of these or other languages which are especially tentative or contentious are preceded by a dagger, †. Direct citations of a written record are enclosed in ⟨angle brackets⟩.

A couple of final phonological points to bear in mind with the examples. Massachusett and other New England languages, Mahican, Cheyenne, and Arapaho have all undergone vowel shifts that can partially obscure the fact that they regularly reflect this or that Proto-Algonquian formation. Some of these deviations will be noted again as they come up, but the key ones are: Massachusett/New England/Mahican ⫽a·⫽ and ⫽ʌ̨·⫽ correspond to PA *e· and *a·; Arapaho reflects *o(·) as i(i); and Cheyenne has e, a, o from *i/*o, *e, and *a, and underlying high tone |é| (etc.) from long vowels. Unless noted otherwise, an example from a daughter language regularly descends from the PA or pseudo-PA form being illustrated (in the portions of the forms relevant to the discussion).

Several commonly recurring but longer language names will be abbreviated. These are: MalPass for Maliseet-Passamaquoddy, Mass for Massachusett, and NipAlg for Nipissing Algonquin. Unless otherwise specified, “Unami” refers to Southern Unami.

A Note on Different Reconstruction Models

Inevitably, not all Algonquianists have agreed on all the details of the phonological processes in the protolanguage. The presentation in this post represents my own personal judgment calls and beliefs; they usually correspond to Ives Goddard’s conclusions, where he has given them, though this is not universally true. Some of the more significant points of disagreement among Algonquianists will be noted or discussed at appropriate points when space allows, but plenty of others, especially minor ones, will have to be passed over.

I only just obtained a copy of David Pentland’s enormous Proto-Algonquian etymological dictionary (Pentland 2023) a few days ago, too late to fully integrate information and viewpoints from it into this post. But in a few places I have unsystematically noted some particularly significant insight, or more often a divergence in views on the protolanguage between Pentland and most others, usually including myself.

Two important general differences exist between the views of Proto-Algonquian held by Pentland and most Algonquianists, with cascading effects on a number of specific rules, so I will address them now. First, Pentland reconstructed pre-PA as containing a contrastive set of glottalized consonants which developed a number of morphophonemic differences from the nonglottalized set prior to merging with it. Morphophonemic processes caused by one set but not the other included triggering of umlaut (see Rules 13a, 13b, and 16), inserting epenthetic *‑o- between *‑ekw‑w- “INV”+“FMV” and *‑wa·w “2pl/3pl” (cf. Rule 9c), being lost morpheme-initially in the formation of deverbals (see Coda ex. 4), and so on.

Regardless of the historical validity of Pentland’s explanation for such differences, the situation by the PA period was more complex, and the processes more morphologized/lexicalized, than his presentation often will allow. Pentland’s treatment of processes such as umlaut thus end up being too simplistic and failing to account for complications (and, in the example of umlaut, of other more serious issues, as discussed in footnote 24 in the appropriate section below).

One of the most important specific properties Pentland ascribes to the glottalized/nonglottalized distinction is that “[f]inal syllables beginning with a nonglottalized sonorant were lost . . . except in words of four syllables or less” (Pentland 1999:254-255).[5] This actually contrasts dramatically with Goddard’s (2007:215-218) rule, adopted here (Rule 28), in which the only loss of final segments is the dropping of any consonants in absolute word-final position. Pentland’s formulation requires significantly more restructuring both in PA and in the daughters, and leads to different hypotheses regarding the relationships among various morphemes (for example, the allomorphs of the N-formative *‑n(ay) or *‑n(e·)—for which see Rule 29—and the collective nominalizer *‑inay and its offshoots—for which see the section on *ayi contraction). Again, I follow Goddard’s position here. For more detailed argumentation, readers may consult the original sources; Pentland and Goddard’s papers, at least, are publicly available (see links in the list of sources at the end of the post).

Second, Pentland’s (esp. 1999) reconstruction of the PA verbal system differs in many ways from Goddard’s (esp. 2007), which is, again, the model I follow for the most part. Some of the differences are minor, but others are quite significant, and often intersect with reconstructions involving the “glottalized”/“nonglottalized” distinction and word-final loss of segments. Proulx’s (esp. 1990) view of the Proto-Algonquian verb was much more radically different than anyone else’s, but also much less defensible, and it and its unique implications are rarely dealt with here.

List of Rules

(1a) The *e of the person prefixes (*ne- “1,” *ke- “2,” *we- “3,” *me- “UNSPEC”) is lost before a vowel-initial dependent noun stem. Rule 1a must precede Rules 1b, 12, 20b, and 22.

e → Ø /#{n,k,w,m}__+V (morphologically conditioned)

- *ne- “1” + *‑i·yaw- “body” → *ni·yawi “my body; myself” (e.g., Miami-Illinois niiyawi)

- *ke- “2” + *‑atay- “belly, stomach” → *katayi “your (sg.) belly, stomach” (e.g., Plains Cree katay, Munsee kătay)

(1b) Before all other vowel-initial stems (= verbs and non-dependent nouns), an epenthetic *‑t- is inserted after the person prefixes. Rule 1b must follow Rule 1a and must precede Rules 2, 12, and 20b.

Ø → t /#{ne,ke,we}+__V (morphologically conditioned)

- *ne- “1” + *api- “sit (AI)” → *netapi “I’m sitting” (e.g., Ojibwe nindab)

- *ke- “2” + *ehkw- “louse” + *‑em “POSS” → *ketehkoma “your (sg.) louse” (e.g., Plains Cree kitihkom)

(2) In PA there was a decent amount of residue of a no-longer-productive palatalization process, termed “Palatalization I” by Pentland (1979:390-392) (as opposed to “Palatalization II” = Rule 25), by which (by the actual PA period) *t became *s before certain specific morphemes beginning in *e, *a·, and rarely *i(·). Rule 2 must follow Rule 1b and must precede Rule 25.

t → s (rare and sporadic, lexically / morphologically conditioned)

- *pye·t- “coming; hither” + *‑a·p “see, vision” [a triggering morpheme] + *‑am “(TA Final)” + *‑a· “3OBJ” + *‑ẅ “3” + *‑a “PROXsg” → *pye·sa·pame·wa “s/he (PROX) sees (s.o. (OBV)) approaching” (e.g., Meskwaki pye·sa·pame·wa)

- Cf. *pye·t- + *‑a·p “dawn” [etymologically identical with *‑a·p “see,” but a different morpheme by the time of PA] + *‑an “(II Final)” + *‑ẅ + *‑i “INANsg” → *pye·ta·panwi “dawn approaches” (e.g., Meskwaki pye·ta·panwi)

- *went- “RR:SOURCE/REASON” + *‑ehk “by foot/body (TI Final)” [a triggering morpheme] + *‑am “INAN.OBJ(CL1)” → *onsehkamwa “s/he comes to (sth.) from {somewhere}, for {such reason}” (e.g., Menominee ohsε·hkam)

- Cf. *went- + *‑en “by hand (TI Final)” + *‑am + *‑ẅ + *‑a → *ontenamwa “s/he gets, takes (sth.) from {somewhere}” (e.g., Menominee ohtε·nam)

- *ne- “1” + *mi·t- “defecate” + *‑i· “(AI Final)” [triggering in this one case] → *nemi·si· “I defecate” (e.g., Ojibwe nimiizii)

- Cf. *ne- + *mi·t- + ‑t “(TI Final)” + *‑am “INAN.OBJ(CL1)” + *‑n(ay) “FMV” + *‑i “INANsg” = **nemi·tta·ni → **nemi·tita·ni [epenthetic *‑i- by Rule 9a] → *nemi·čita·ni [*ti → *či by Rule 25] “I defecate on it” (e.g., Ojibwe nimiijidaan)

- Cf. also *ne- + *mi·t- + *‑enkwa·m “sleeping (AI Final)” → *nemi·tenkwa·me “I defecate in my sleep, shit my bed” (e.g., Ojibwe nimiidingwaam)

- It’s probable that in PA, Palatalization I had been lexicalized to enough of an extent where other morphemes could intervene between the trigger and the *t affected, since this is the case in some daughters, e.g. (Goddard 2001:202): *na·kat‑aw- “follow” + *‑a·p “see, vision” [a triggering morpheme, see first example above] + *‑am “(TA Final)” → **na·katawa·pame·wa → *na·kasawa·pame·wa “s/he (PROX) keeps h/ eye on, carefully observes (s.o. (OBV))” (Meskwaki na·kasawa·pame·wa)

- Cf., with assibilation evidently leveled out, e.g.: Plains Cree nākatawāpamēw, Ojibwe [o]naagadawaabam[aan]

(3) The animate third-person conjunct suffix *‑t becomes *‑k after a consonant. Rule 3 must precede Rules 7, 8c, 9a, 9b, 11, 25, 26, 27a, and 27b.

t → k /C+__ (morphologically conditioned)

- *takwihθin- “arrive (AI)” + *‑t “3AN.CONJ” + *‑e· “SBJV” → *takwihšinke· “if s/he arrives” (e.g., Ojibwe dagoshing)

- Cf. *pi·ntwike·- “enter (AI)” + *‑t + *‑e· → *pi·ntwike·te· “if s/he enters” (e.g., Ojibwe biindigeed)

- *pya·- “come (AI)” + *‑t + *‑e· → *pya·te· “if s/he comes” (e.g., Munsee páate) vs. *pya·- + *‑w “IRR” + *‑t + *‑e· → **pya·wke· → *pya·kwe· [by Rule 7] “if s/he doesn’t come” (e.g., Munsee páakwe, Meskwaki [me·hi‑]pya·kwe “before s/he came/comes”)

- *na·θ- “fetch (TA)” + *‑ekw “INV” + *‑t + *‑a “PROXsg.PART” + IC → **naya·θekwka → *naya·θekoka “s/he (PROX) who is fetched by h/ (OBV)” (e.g., Munsee ‡náalkwək[S6]) (see Goddard 1979a:110, n. 15, 1979b:132, 2015b:375)

- But analogically reshaped in nearly all daughters to contain the more common *‑t allomorph (e.g., Ojibwe nayaanigod, Meskwaki ‡na·nekota, Menominee ‡naya·nekot, Arapaho ‡nonooθéit “s/he (OBV) goes and gets h/ (PROX)”) (cf. Goddard 2015b:375)

(4a) *h is lost between two consonants. Rule 4a must precede Rules 5 (at least as a historical sound change), 9a, 26, and 27a.

h → Ø /C__C

- *wa·pant- “look at (TI)” + *‑am INAN.OBJ(CL1) + *‑hk “POT” + *‑an “2sg.CONJ” → **wa·pantamØkani → *wa·pantankani [nasal assimilation by Rule 26 = 27a(iii)] “lest you (sg.) look at it” (e.g., Ojibwe [geego] waabandangeen “don’t (sg.) see it!”)

- *wa·pant- + *‑am + *‑hsi “DIM” + *‑w “IRR” + *‑ẅ “3” + *‑a “PROXsg” → **wa·pantamØsi·wa → *wa·pantansi·wa “s/he doesn’t look at (sth.) even a little bit” (e.g., Miami-Illinois waapantansiiwa “s/he doesn’t look at it,”[S7] Ojibwe [gaawiin] owaabandanziin “s/he doesn’t see it”)

- *wera·ke·‑e·n- “bowl, dish” + *‑hs “DIM” + *‑i “INANsg” → *ora·ke·nØsi “small bowl, small dish” (e.g., Unami lɔ́·k·e·ns “dish”) (cf. Goddard 1974:326, n. 66, 1979a:92)

- For another probable example of Rule 4a, in the form of an actual sound change operating in pre-PA, see: *name·kw- “*fish” [→ “lake trout (Salvelinus namaycush)”] + *‑hs + *‑a “PROXsg” → **name·kwsa → *name·ʔsa “fish” (cf. Goddard 1979a:92, 2008b:7; mentioned in the discussion on “*xC” and *ʔC clusters in the Proto-Algonquian post)

- Similarly: *e·h- “bivalve mollusk” + *‑hs + *‑a = *e·hhsa → *e·hØsa “bivalve mollusk, clam, etc.; shell” (e.g., Ojibwe ees, Miami-Illinois eehsa, Menominee ε·hs[e·hsεh]; cf. Munsee éehəs ~ éehas and Unami é·həs, reflecting post-PA *e·hehsa, the original stem *e·h- plus later regular diminutive *‑ehs) (cf. Goddard 2008b:7)

(4b) There were at least two clear exceptions to Rule 4a of which I’m aware. The first was that *θhs resolved to *hs, not xθs, which was an illegal cluster. Perhaps the rule more broadly was that the *‑h- was deleted when an (intermediate) legal cluster would result, and otherwise the first consonant in a *ChC sequence was deleted, leaving a final legal *hC cluster? Rule 4b must precede Rule 9a.

θ → Ø /__hs (/__hC ?)

- *wa·pam- “look at (TA)” + *‑eθ “2OBJ” + *‑hs “DIM” + *‑w “IRR” + *‑a·n “1sg.CONJ” → **wa·pameØhsowa·ni “when I don’t look at you (sg.) even a little bit” [opaque due to the seeming absence of the theme sign *‑eθ, and repaired by different daughters by re-inserting *‑eθ:]

- → pseudo-PA *wa·pamehseθowa·ni (Ojibwe waabamisinowaan “if I don’t see you (sg.)”)

- → pseudo-PA **wa·pamehsoweθa·ni → *wa·pamehso·θa·ni (Miami-Illinois waapamehsoolaani “I don’t look at you (sg.),”[S8] Cheyenne [tsés-sáa‑]vóomáhetse |=vóom-aʹhéte| “when I didn’t see you (sg.)”)

- *ne- “1” + pre-PA *‑šiθ- “father-in-law” + *‑hs “DIM” + *‑aki “PROXpl” → *nešiØhsaki “my maternal cross-uncles” (e.g., Menominee nese·hsak) (Goddard 1979a:92)

(4c) The second exception to Rule 4a is that when the irrealis suffix *‑w was followed by the potential/admonitive suffix *‑hk, the cluster remained as such (including when an *m preceded). This *(m)whk cluster is resolved later via the insertion of epenthetic vowels by Rules 6 and 9a (and the *w is lost through the contraction of the resulting *VwV sequence, by Rule 21). Rule 4c must precede Rules 6, 7, 9a, and 21.

- *menah- “give to drink (TA)” + *‑i “1OBJ” + *‑w “IRR” + *‑hk “POT” + *‑e·kw “2pl.CONJ” → **menahiwhke·kwi → **menahiwehke·kwi → *menahi·hke·kwe “you (pl.) should not neglect to give me a drink” (e.g., Plains Cree minahīhkēk “(you pl.) give me a drink later!”)

- *weten- “take (TI)” + *‑am “INAN.OBJ(CL1)” + *‑w + *‑hk + *‑e·kw → **wetenamwhke·kwi → **wetenamowehke·kwi → *otenamo·hke·kwe “you (pl.) should not neglect to take it” (e.g., Plains Cree otinamōhkēk “(you pl.) take it later!”)

(5a) In a sound change of pre-PA date (“Meeussen’s Law” [see Meeussen 1959]), in sequences of a plosive + a true consonant, the plosive lenited, ultimately becoming *ʔ in most cases, but *s before *p and *k (see the discussions here and here); in the operation of the rule, any intervening semivowel and/or consonant immediately preceding the plosive were dropped. Meeussen’s Law is mostly irrelevant to synchronic PA phonology, with the productive resolution of illicit consonant clusters being the insertion of an epenthetic vowel (see Rules 6 and 9a), but there remained some archaic combinations where the effects of the change were still visible, and which may have been analyzed as such by speakers. Rule 5a must precede Rule 9a, and forms a component of Rule 9e(=9a); at least as a historical sound change it followed Rule 4a.

(C){p,t,k}(G) → s /__{p,k} (sporadic, lexically conditioned)

(C){p,t,k}(G) → ʔ /__C[≠G] (sporadic, lexically conditioned)

- Cf. the stems *neʔr- “kill (TA)” ← *nep- “die” + *‑r “(TA Final)” (i.e. “cause to die”) vs. plain *nep- “die (AI)” ← *nep- (e.g., Menominee nepwa·h “s/he dies,” nεʔnεw “s/he (PROX) kills h//them (OBV))

- Cf. the four basic derivationally related stems for “placing,” all derived from the Initial/root *ap- “located ({somewhere}), placed, in place; exist ({somewhere})”:

- AI *api- “sit ({somewhere}); be (in place {somewhere}); exist ({somewhere})” ← *ap- + *‑i “(AI Final)” (e.g., Menominee ape·w “s/he’s in place (etc.),” Munsee ăpə́w “s/he’s there”)

- II *aʔte·- “be (located; placed) {somewhere}, be in place; exist ({somewhere})” ← *ap- + *‑te· “(II Final)” (e.g., Menominee aʔtεw “it’s in place (etc.),” Munsee áhteew “it’s there”)

- TI *aʔtaw- “place, set sth.” ← *ap- + *‑t “(TI Final)” + *‑aw “INAN.OBJ(CL2)” (e.g., Menominee aʔtaw “s/he has it ({somewhere}), places it; she (hen) lays it (an egg),” Munsee áhtoow “s/he puts (sth.) down”)

- TA *aʔr- “place s.o.” ← *ap- + *‑r “(TA Final)” (e.g., Menominee aʔnεw “s/he (PROX) has, places h/ (OBV) ({somewhere}), has h/ (OBV) at h/ (PROX) disposal,” Munsee áhleew “s/he (PROX) puts (s.o. (OBV)) down”)

- *‑t “3AN.CONJ” + *‑pan “EMPH.PAST” → verb ending *‑span “3AN.CONJ.EMPH.PAST”: e.g., *pemwehθe·- “walk along (AI)” + *‑t + *‑i “INDIC” = **pemwehθe·ti → *pemohθe·či “when s/he walks along” vs. *pemwehθe·- + *‑t + *‑pan + *‑i → *pemohθe·spani “when s/he had walked along” (e.g., Moose Cree pimohtēt vs. pimohtēspan “s/he would walk along”)

- Cf. *‑pan with other person suffixes, e.g., *‑a·nk “1pl.EXCL.CONJ” + *‑pan → verb ending *‑a·nkepan (with epenthetic *‑e-) “1pl.EXCL.EMPH.PAST”: e.g., *pemwehθe·- + *‑a·nk + *‑i → *pemohθe·ya·nki “when we (excl.) walk along” vs. *pemwehθe·- + *‑a·nk + *‑pan + *‑i → *pemohθe·ya·nkepani “when we (excl.) had walked along” (e.g., Moose Cree pimohtēyāhk vs. pimohtēyāhkipan “we (excl.) would walk along”) (For a unified account of epenthesis patterns involving *‑pan, see Rule 9e)

(5b) While Meeussen’s Law normally gave *sp, *sk as the outcomes of earlier / underlying *t‑p, *t‑k, in a few cases it resulted in *hp, *hk instead (Goddard 2015b:406, n. 91).

t → h /__{p,k} (rare, sporadic, lexically conditioned)

- *wi·t- “with another” + *‑pe· “sleep” + *‑m “(TA Final)” → stem *wi·hpe·m- “sleep with (TA)” (e.g., Plains Cree wīhpēm-, Arapaho in nenííčoobéθen “I’m sleeping with you (sg.)” [with level high pitch on íí indicating pre-Arapaho stem *ni·čo·m-, with plain *č ← PA *(h)p but not *sp], Cheyenne |véám‑| [with Ø ← PA *(h)p but not *sp])

- Cf. *wet- “pull, draw” + *‑pwa· “by mouth (AI Final)” → stem *ospwa·- “smoke a pipe (AI)” (with expected *sp cluster) (e.g., Plains Cree in derivative ospwākan “pipe”; Arapaho hîičoo- [← pre-Arapaho *iʔčoo-], Cheyenne he’pó-)

- The daughters offer conflicting evidence over the outcome when an II stem ending in *t was followed by the suffix *‑k “INAN.CONJ”: thus, Unami points to *hk, while Gros Ventre points to *sk. Many others are ambiguous. Perhaps there was variation in PA. Thus:

- *tahka·skwat- “be shade, shady (II)” + *‑k “INAN.CONJ” + *‑i “RRC.PART” + *e·ntaθi= “where it is” → ?*e·ntaši=tahka·skwahki “where it’s shady, in the shade” (Unami enta-thá·kɔ |=tahāhkwa|, with loss of pre-Unami final *|‑h| ← PA *hk [vs. Unami |hk| from PA *sk, which would have been retained]) (Goddard 1979b:129)

- *tawat- “be a gap (II)” + *‑k + *‑i “INANsg.PART” + IC → ?*te·waski “that which is a gap, hole” (Gros Ventre tɔ́ɔ́nʔɔ “it is or has a hole,” with /ʔ/ ← PA *sk)

(6) When directly following a consonant, several suffixes beginning with a labial element insert a preceding epenthetic *‑o- (typically referred to as “connective *o”): (i) the irrealis *‑w; (ii) the 2pl imperative *‑kwe; and (iii) the plural augment *‑wa· when it occurs before the third-person suffix *‑t, viz. in a participle or the iterative.

In derivation, epenthetic *‑o- is added before (iv) the nominalizer *‑ẅen and (v) a suffix *‑ẅ which creates Initials from verb stems. (*‑ẅen is etymologically this *‑ẅ + the nominalizer *‑en.) The *‑o- before derivational *‑ẅ and/or *‑ẅen was lengthened to *‑o·- in a number of daughter languages. And it’s plausible that (vi) the relational *‑w also used *‑o-, as in Meskwaki and Ojibwe, but this is difficult to say with confidence; in many varieties of Cree it takes no epenthetic vowel, and Cheyenne shows a third pattern. Morphemes which fail to insert an epenthetic *‑o(·)- include: the formatives *‑w “W.FMV” and *‑ẅ “3” (but see below); the suffix *‑wa·w “2pl/3pl”; and the derivational suffixes *‑w and *‑ẅ. Finally, note that (vii) contrary to its normal behavior, *‑ẅ “3” does insert *‑o- when it is both preceded and followed by a consonant, viz. when it precedes a consonant-initial mode suffix (*‑pan “EMPH.PAST” and *‑(e)sahan “EMPH.PRES”; on this exception, see also Rule 9e).

A number of these morphemes, both those which added epenthetic *‑o- and those which failed to, are etymologically connected. Thus, the plural augment *‑wa· (6(iii)) is cognate with the 2pl/3pl suffix *‑wa·w, while the non-epenthesizing derivational suffixes *‑w and *‑ẅ are etymologically the same as the two formatives. The non-epenthesizing derivational *‑ẅ and formative *‑ẅ “3” are also likely both ultimately the same as the epenthesizing derivational *‑ẅ (and thus the initial portion of the nominalizer *‑ẅen) (6(iv), 6(v)).

In the operation of Rule 6, word-initial *e- (in practice, only the verb stem *e- “say {so} (AI)”) was treated as if it were *ey- (Goddard 2000:126, n. 56; cf. 2003:98, n. 47), so *e- plus a relevant *w became *ey‑o‑w…; several examples will be found below. Rule 6 must follow Rule 4c, must precede Rules 7, 17, 18, 19, 20b, 21, and 22, and forms a component of Rule 9e(=9a).

Ø → o /C__+{w,ẅ,kw} (morphologically conditioned)

- *ne- “1” + *wem- “come from {somewhere} (AI)” + *‑w “IRR” + *‑eʔm “FMV” = **newemweʔm → **newemoweʔm → *no·mowe “I don’t come from {somewhere}” (e.g., Unami nú·mu·wi [Goddard 1979b:168])

- *tahkwen- “hold, sieze (TI)” + *‑am “INAN.OBJ(CL1)” + *‑kwe “2pl.IMPER” → **tahkwenamkwe → *tahkonamoko “(you pl.) hold, sieze it/them (INAN)!” (e.g., Moose Cree tahkonamok)

- *wi·nke·rent- “like, find pleasing, good (TI)” + *‑am + *‑wa· “AUGMT:pl” + *‑t “3AN.CONJ” + *‑iri “ITER” + IC → *wa·nke·rentamwa·tiri → *wa·nke·rentamowa·čiri “whenever they like it/them (INAN)” (e.g., Arapaho nííʔeenêetowunóóθi [u from *i ← *o by vowel harmony])

- *nep- “die (AI) + *‑ẅen “NMLZ” → **nepweni → *nepoweni “death” [→ post-PA *nepo·weni] (e.g., Meskwaki nepo·weni, Ojibwe nibowin [likely with secondarily analogically short o])

- *nep- + *‑ẅ “AI⇒Initial” + *‑e·rem “think, feel (TA Final)” → **nepwe·rem- → stem *nepowe·rem- “think s.o. to be dead (TA)” [→ post-PA *nepo·we·rem-] (e.g., Meskwaki nepo·we·nem-)

- Another example with the same stem: pseudo-PA *nep- + *‑ẅ + *‑a·‑ka‑n “NMLZ” → **nepwa·kani → *nepowa·kani “death” [→ PEA *nəpəwākan] (e.g., Mass ⟨nupꝏonk⟩ ⫽nəpəwʌ̨·k⫽, Penobscot nə̀pəwαkan)

- Cf. also: *e- [→ *ey-] “say {so} (AI)” + *‑ẅen or *‑ẅ‑a·kan → **eyweni / **eywa·kani → *eyoweni / *eyowa·kani “thing said, what is said” (e.g., Meskwaki iyoweni “word, thing said”; Mass ⟨yeuwonk⟩ ⫽yəwʌ̨·k⫽ “word”)

- *mešot- “shoot and hit (TI)” + *‑am “INAN.OBJ(CL1)” + *‑w “RELN” + *‑a· [→ *Ø by Rule 10] “3OBJ” + *‑ak “1sg»3AN.CONJ” → **mešotamwaki → ?*mešotamowaki “that I hit it with my shot in relation to h//them (e.g., I hit h/ item)” (Ojibwe mizhodamowag, Meskwaki ‡mešotamowaki[S9])

- But cf. Western Swampy Cree [kā-kī‑]wāpahtamwak “when/then I saw it in relation to h//them” (Cenerini 2014:79), with wāpaht‑am- “see (TI)”

- Formative *‑ẅ normally does not insert *‑o-: *nep- “die (AI)” + *‑ẅ “3” + *‑a “PROXsg” → *nepwa “s/he dies” (e.g., Meskwaki nepwa, Mass ⟨nup⟩ ⫽nəp⫽ |nəpẅ| [Exod. 11:5])

- But does so when between two consonants: *nep- + *‑ẅ + *‑pan “EMPH.PAST” → **nepowpan → *nepo·pa [see Rule 9e] “s/he had died” (e.g., Meskwaki ‡nepo·pani “s/he is surely dead, is dead indeed,” Mass ⟨nupoop⟩ ⫽nəpu·p⫽ “s/he died”)[10]

- Cf. also: *e- [→ *ey‑] “say {so} (AI)” + *‑ẅ + *‑sahan “EMPH.PRES” → **eywsahan → **eyowsahan → ?*eyowesaha [or ?*eyo·saha] “s/he has said {so}” (e.g., Menominee eyo·sah “so s/he says {so}”) [uncertain example]

- Cf. as well the different treatment before vowel-initial mode suffix: *pankihθen- “fall (II)” + *‑ẅ + *‑etoke·h “DUB” = **pankihθenwetoke·h → *pankihθenotoke· [*‑o- ← *‑we- by Rule 20b] “it must have fallen” (e.g., Ojibwe bangisinodog; cf. variant bangisinowidog with analogically extended *o-insertion, as if from xpankihsenowetoke·)

(7) The sequence *wk, when following a vowel, metathesizes to *kw. Rule 7 must follow Rules 3, 4c, and 6, must precede Rules 9a/9b, 11, 19, 20b, and 22, and forms a component of Rule 27b.

wk → kw /V__

- *ki·šiht- “finish (TI)” + *‑aw “INAN.OBJ(CL2)” + *‑t “3AN.CONJ” + *‑e· “SBJV” → **ki·šihtawke· [by Rule 3] → *ki·šihta·kwe· “if s/he finishes it” (e.g., Munsee kiishihtáakwe) [see also Rule 27b(iv)]

- *aθet- “rot (II)” + *‑w “IRR” + *‑k “INAN.CONJ” + *‑e· “SBJV” → **aθetowke· → *aθetokwe· “if it doesn’t rot” (e.g., Munsee alətóokwe)

- *neʔr- “kill (TA)” + *‑i “1OBJ” + *‑w “IRR” *‑t “3AN.CONJ” + *‑e·n “INTERR” + *‑a “PROXsg.PART” + IC → **ne·ʔriwke·na → *ne·ʔrikwe·na “whoever may kill me” (e.g., Ojibwe neesigween, Meskwaki ‡ne·sikwe·na)

(8a) Several morphemes lose their final consonant before a mode suffix. First, the independent order pluralizers *‑ena·n “1pl.EXCL” and *‑wa·w “2pl/3pl” lose their final *n or *w, respectively. (For a few complications to this statement, see the Coda, exs. 1 and 2, below.) Rule 8a must precede Rules 9a, 12, and 26, and forms a component of Rule 9e(=9a).

ena·n → ena· /__+{pan,(e)sahan,etoke·h,…} (morphologically conditioned)

wa·w → wa· /__+{pan,(e)sahan,etoke·h,…} (morphologically conditioned)

- *ne- “1” + *ne·w- “see (TA)” + *‑a· “3OBJ” + *‑ʔm “FMV” + *‑ena·n “1pl.EXCL” + *‑pan “EMPH.PAST” → **nene·wa·ʔmena·npan → *nene·wa·ʔmena·pa “we (excl.) had seen (s.o.)” (e.g., Unami nne·ɔ́həna·p |nənēwāhmənāp|)

- *ne- + *kweʔθ- “fear (TA)” + *‑a· + *‑w “FMV” + *‑ena·n + *‑etoke·h “DUB” → **nekweʔθa·wena·netoke·h → **nekweʔθa·wena·Øetoke·h → ?*nekoʔθa·wena·toke· [with *‑a·‑e- → *‑a·-] “it seems we’re (excl.) afraid of h/” (e.g., Ojibwe ningosaanaadog, Meskwaki ‡nekosa·[pe]na·toke)

- *ke- “2” + *pya·- “come (AI)” + *‑ʔm + *‑wa·w “2pl/3pl” + *‑(e)sahan “EMPH.PRES” = **kepya·ʔmwa·w(e)sahan → *kepya·ʔmwa·saha “you (pl.) have come” (e.g., Menominee kepya·mwa·sah “so you (pl.) have come”)

(8b) Second, as attested by Arapahoan, Cree-Innu (CINA), and Unami, the conjunct 1sg suffix *a·n loses its final *n before the same mode suffixes. Although the same process may also have occurred with the 2sg.CONJ suffix *‑an, it would only unambiguously be reflected in some varieties of Cree (I think?); these probably instead have reshaped the 2sg endings by analogy with the 1sg ones, but there’s room for doubt (cf. Proulx 1990:107). Rule 8b must precede Rules 9a, 26, and possibly 12, and forms a component of Rule 9e(=9a).

a·n → a· /__+{pan,(e)sahan,…} (morphologically conditioned)

an → a /__+{pan,(e)sahan,…} (morphologically conditioned) (possibly [??])

- *pya·- “come (AI)” + *‑a·n “1sg.CONJ” + *‑pan “EMPH.PAST” → **pya·ya·npane· → *pya·ya·pane· “if I had come” (e.g., Unami pa·á·p·ane |pā-yā-pan-ē| ← |pā-ān-pan-ē|)

- *api- “sit ({somewhere}); be placed, located {somewhere} (AI)” + *‑an “2sg.CONJ” + *‑pan → ?*apiyampani “you (sg.) had sat, been there” (e.g., Ojibwe abiyamban)

- But cf. Moose Cree apiyapan, as if from ?*apiyapani [not xapiyahpan with ‑hp- ← *‑mp‑]; probably by analogy with 1sg apiyāpān ← *apiya·pani

- *tankam-etwi- “hit e.o. (AI)” + *‑a·n + *‑(e)sahan “EMPH.PRES” → pseudo-PA *tankametwiya·sahane· [as if meaning “if I have, do hit myself”] (e.g., Arapaho tóʔobétinóóhk “if I strike myself”)

- Note that the ending ‑nóóhk is regular from post-PA *‑y‑a·sapan, with *‑(e)sahan reshaped as *‑(e)sapan; x‑y‑a·nsapan would have given Arapaho x‑noohʔók (cf. Goddard 2015b:407, n. 102), and x‑y‑a·nesapan, with epenthetic or segmental *e, would have given something like x‑noonóhk

(8c) Finally, it seems that the 3AN.CONJ suffix *‑t was dropped before *‑(e)sahan “EMPH.PRES.”[11] This appears to have only applied to the postvocalic *‑t allomorph of the 3AN.CONJ suffix, not the postconsonantal *‑k one. Rule 8c must follow Rule 3, and possibly must precede Rules 9a and 12.

t → Ø /__+(e)sahan (morphologically conditioned)

- *tankam- “hit (TA)” + *‑a· “3OBJ” + *‑t “3AN.CONJ” + *‑(e)sahan → **tankama·t(e)sahane· → *tankama·sahane· “if s/he (PROX) has hit h/ (OBV)” (e.g., Arapaho tóʔowoohók “if s/he (PROX) strikes h//them (OBV)” [‑oohók ← post-PA *‑a·sapan, or theoretically *‑a·hsapan])

- Cf. outcome with other morphemes ending in *‑t: *tankam- + *a· [→ *Ø by Rule 10] + *‑at “2sg»3AN.CONJ” + *‑(e)sahan → *tankamatesahane· “if you (sg.) have hit h/” (e.g., Arapaho tóʔowotéhk “if you (sg.) strike h/” [‑otéhk ← post-PA *‑atesapan])

- *tepe·rem- “judge; manage, control, rule (TA)” + *‑a· + *‑t + *‑(e)sahan → *tepe·rema·sahane· “if s/he (PROX) has ruled h/ (OBV)” (e.g., Old Algonquin ⟨[tiberima]zen⟩ †tipērimāsan [Nicolas 1674:25, “s’il l[’eut ou s’il l’auoit gouuerné]”; Daviault 1994:77; cf. Pentland 1984; equivalent to a modern *dibeenimaazan])

- Cf. Western Abenaki ⟨wajônôza⟩ [wskəbi] wajʌ̨nʌ̨za “perhaps s/he (PROX) had h//them (OBV)” (Laurent 1884:156) with verb wajʌ̨n- “have, possess (TA)” and ‑ʌ̨za /‑ʌ̃sa/ (← *‑a·sa…, not [in this paradigm] /ss/ ← *‑hs- or *‑ʔs-)

- Cf. also Mass ⟨wadchanós⟩ †⫽wačʌ̨·nʌ̨·s⫽ “if he s/he (PROX) did keep, have h//them (OBV)” (Eliot 1666:40; Goddard and Bragdon 1988:566) with cognate verb ⫽wačʌ̨·n-⫽ “keep, have, preserve (TA)” and †⫽-ʌ̨·s⫽ (consistently spelled with single ⟨s⟩ = †⫽s⫽ ← *‑s-, never with an indication of ⫽hs⫽ ← *‑hs- or *‑ʔs-)

(9a) An epenthetic vowel, either *‑e- or *‑i- (normally referred to as “connective *e” and “connective *i”), is inserted to break up most consonant clusters across a morpheme boundary.[12] It’s often difficult to determine when Rule 9a actually operated, because in many cases it’s hard or impossible to choose whether to segment a given morpheme as, say, *e-initial and losing the *e when following another vowel (by Rule 12 below), or as *C-initial and inserting an epenthetic *‑e- by Rule 9a when it follows a consonant. There are sometimes clues which help solve the question, though. Rule 9a must follow Rules 3, 4a, 4b, 4c, 5a/5b, 8a, and possibly 8b and 8c, must precede Rules 14, 20a, 20b, 21, and 25, and forms a component of Rules 9e(=9a), 27b, and 29.

Ø → e /C+__C (morphologically / lexically conditioned)

Ø → i /C+__C (morphologically / lexically conditioned)

- *šekwah- “crush by tool (TI)” + *‑ike· “ANTIP (AI Final)” → *šekwahike·- “crush (things) by tool (AI)” (e.g., Ojibwe zhishigwa’igee- [reduplicated], Munsee shkwahiikee-)

- Cf., showing that the *‑i- of *‑i-ke· is (historically) epenthetic: *ahšam- “feed, give food to (TA)” + *‑ke· → *ahšanØke·- “feed (people), serve a meal (AI)” with no epenthetic vowel (e.g., Ojibwe ashangee-, Munsee xankee-)[13]

- *nep- “die (AI)” + *‑t “3AN.CONJ” + *‑e· “SBJV” = **nepte· → **nepke· [*‑t → *‑k after a consonant, by Rule 3] → *nepeke· “if s/he dies” (e.g., Meskwaki nepeke, Miami-Illinois nipeke, Menominee nepε·k, Mass ⟨nuppuk⟩ ⫽nəpək⫽ [Matt. 22:24][14])

- Epenthetic status of *‑e- is confirmed by the postconsonantal allomorph of the following consonant (see Rule 3), and cf. as well, with no epenthetic vowel: *nep- + *‑ẅ “3” + *‑a “PROXsg” → *nepØwa “s/he dies” (e.g., Meskwaki nepwa, Miami-Illinois nipwa, Menominee nepwa·h, Mass ⟨nup⟩ ⫽nəp⫽ |nəp‑ẅ| [Exod. 11:5; vs. analogical ⟨nuppꝏ⟩ ⫽nəpəw⫽, with vowel added, in Gen. 48:7])

(9b) Rule 9a failed to apply with certain specific morphemes and morpheme combinations. As the rules are ordered here, the primary exceptions to the insertion of an epenthetic vowel were: (i) between any consonant and a following semivowel; (ii) between any nasal and any consonant (later turned into legal clusters by Rule 26); and (iii) between synchronically legal clusters. If Rule 9a were ordered earlier, as some people have placed it, it would be necessary to specify additional environments where no epenthetic vowel was inserted.[15] The results of the combination of legal cluster elements were: (iv) *h + *C → *hC (weakly supported, but plausible as a general rule); (v) *š + *C → *šC; and (vi) *θ + *C → *θC (Pentland 1979:363-390; Goddard 1979a:107-108, n. 4, 1997:32). *ʔC and *sC clusters derive from Meeussen’s Law as illustrated earlier (Rule 5a); and nasal clusters, from any *N + any *C, resolve to legal *NC sequences by Rule 26 as just mentioned. The origin of the clusters *rk and *rp, as well as the cluster I write *ʔm—but which might have been *hm (Goddard’s preference) or *mm—is unknown. Putative *čC clusters appear to have had several sources and may not even have been real.

- For examples of *Cw / *Cy taking no epenthesis, see Rules 9c(=9a), 9d(=9a), 17, and 18 (and 6), which resolve any illegal clusters so created.

- *h + *C = *hC (cf. Pentland 1979:371):

- *re·h~ “REDUP [≈REPETITIVE] + *re·- “breathe (AI)” → *re·hre·wa “s/he breathes” (e.g. Shawnee leʔθe, Menominee nε·hnεw)

- Cf. unreduplicated *re·- in *re·wa “s/he breathes,” reflected in archaic Munsee *léew (not directly attested, but derived noun léewan “breath” attested, in the possessed forms ⟨n’lay whun⟩ nléewan “my breath” and ⟨w’laywun⟩ wə̆léewan “his breath”; cf. normal leexéewan “breath” ← léexeew “s/he breathes,” the reflex of the reduplicated form above [Goddard 2013:110])[16]

- *š + *C = *šC:

- *ki·š- “finish, complete” + *‑pwi “eat, taste, by mouth (AI Final)” + *‑ẅ “3” → *ki·špowa “s/he eats h/ fill, is full, sated” (e.g., Moose Cree kīšpow, Munsee kíispəw)

- *θ + *C = *θC:

- *tankam- “hit (TA)” + *‑eθ “2OBJ” + *‑t [→ *‑k by Rule 3] “3AN.CONJ” → *takameθke· “if s/he hits you (sg.)” (e.g., Penobscot takáməske “if s/he/they hit(s) you (sg.)” [Quinn 2015:[30]])

- With the previous, cf.: *tankam- + *‑eθ + *‑w “IRR” + *‑t [→ *‑k] → **tankameθowke· → *tankameθokwe· “if s/he doesn’t hit you (sg.)” (e.g., Penobscot [ὰta] takáməlokke [ibid.])

- *keθ- “held firmly” + *‑piswi “be tied (AI Final)” + *‑ẅ → *keθpisowa “s/he is tied up” (e.g., Mass ⟨kishpissu⟩ ⫽kəspəsəw⫽ [Matt. 21:2], Munsee koxpíisəw)

(9c) (= 9a) Rule 9a did apply in certain ~exceptions to the exceptions~ captured by Rule 9b(i), however. Epenthetic *‑e- was inserted before *‑wa·w “2pl/3pl” in at least two cases: (i) following a consonant cluster (e.g., after the inverse theme sign *‑ekw + W-formative *‑w); and (ii) per the notation used here, following the N-formative *‑n(ay). In both cases, the resulting sequences of vowels and semivowels coalesced to *o or contracted to *e· by later rules (20b and 21; see also Rule 29(i)). As Goddard (2007:232; see also 2001:170) observes, the first case “can be explained by” the fact that *‑wa·w always takes the same preceding coalescence pattern, etc., as the first-person plural suffixes (inclusive *‑enaw, exclusive *‑ena·n) “in the same paradigm.” Thus, e.g., *‑ekw‑w‑wa·w‑a (PROXsg»2pl.INDEP) becomes **‑ekw‑w‑e‑wa·w‑a → *‑ekowa·wa, just as (PROXsg»1pl.INCL.INDEP) *‑ekw‑w‑naw‑a becomes *‑ekw‑w‑e‑naw‑a → *‑ekonawa. Rule 9c must precede Rules 18, 20b, and 21, and is a component of Rule 29.

Ø → e /CC__+wa·w

Ø → e /n(ay)__+wa·w (morphologically conditioned)

- *ke- “2” + *na·θ- “fetch (TA)” + *‑ekw “INV” + *‑w “FMV” + *‑wa·w “2pl/3pl” + *‑a “PROXsg” = **kena·θekwwwa·wa → **kena·θekwwewa·wa → **kena·θekwowa·wa → *kena·θekowa·wa “s/he fetches you (pl.)” (e.g., Ojibwe ginaanigowaa)

- *ke- + *‑i·θemw- “cross-sibling-in-law” + *‑wa·w → **ki·θemwwa·wa → **ki·θemwewa·wa → *ki·θemowa·wa “your (pl.) cross-sibling-in-law” (e.g., Ojibwe giinimowaa, Cheyenne étamēvo |Ø-étam-evó| [Goddard 2000:87])

- *ke- + *na·t- “fetch (TI)” + *‑n(ay) “N.FMV” + *‑wa·w + *‑i “INANsg” = **kena·tnaywa·wi → **kena·tenayewa·wi → *kena·tene·wa·wi “you (pl.) fetch it” (e.g., Ojibwe ginaadinaawaa [with *e· regularly “recontracted” to aa])

(9d) (= 9a) Another ~exception to an exception~ to Rule 9a was that epenthetic *‑e- was inserted between irrealis *‑w and a following *w (either *‑ẅ “3” or, in theory, the W-formative *‑w—though there are no examples of the latter that survived into the daughters). As with Rule 9c(ii), the resulting *V‑w‑e sequence is contracted to *V· by Rule 21. Rule 9d must precede Rules 18, 20b, and 21.

Ø → e /w+__{ẅ,w} (morphologically conditioned)

- *wi·ʔθenyi- “eat (AI)”[17] + *‑hsi “DIM” + *‑w “IRR” + *‑ẅ “3” + *‑aki “PROXpl” → **wi·ʔθenyihsiwwaki → **wi·ʔθenyihsiwewaki → *wi·ʔθenyihsi·waki “they don’t eat even a little bit” (Ojibwe wiisinisiiwag “they don’t eat,” Miami-Illinois wiihsinihsiiwaki “id.”)

(9e) (= 9a) A final ~exception to an exception~ (of sorts) to Rule 9a are the cases in which epenthetic vowels were inserted before the mode suffix *‑pan “EMPH.PAST,” which as noted a few times, originally did not take epenthesis, though synchronically in PA it often did. In fact, I will use this opportunity to present here a unified account of the epenthesis processes as they relate to *‑pan, instead of leaving bits and pieces scattered among many rules and examples—though some of these processes are also mentioned elsewhere.[18]

When the consonant preceding *‑pan was a nasal or the morpheme *‑t “3AN.CONJ,” no epenthetic vowel was inserted; this is likely also true of *‑ẅ “3” and the formative *‑w. The *t became *s by Meeussen’s Law (5a; example given there), while some nasals were deleted (Rules 8a and 8b; examples given there) and any that remained were kept as is, to eventually assimilate to *m (per Rules 9b(ii) and 26). The case of the formative *‑ʔm before *‑pan is complicated, and I don’t have space to discuss it in full here—hopefully in a future post.

Assuming there was no epenthetic vowel inserted after the formatives *‑ẅ and *‑w, these dropped and the preceding vowel was lengthened (or the whole *Vw sequence preceding *p coalesced); see below in the discussion of contraction. Regardless of whether it took a following epenthetic *‑e- or not, *‑ẅ, unlike its normal behavior (see Rule 6, esp. 6(vii)), inserted a preceding epenthetic *‑o- if it also followed a consonant. The final *w of *‑wa·w “2pl/3pl” may also have been lost before *‑pan, though this is not entirely certain (see discussion in Coda ex. 1).

In most other cases, a preceding epenthetic *‑e- was inserted, viz.: after (i) the formative *‑n(ay) (and possibly after the formatives *‑w and *‑ẅ “3”); (ii) the central suffix *‑enaw “1pl.INCL”; and (iii) the conjunct non-singular and portmanteau central suffixes. Note that the synchronic phonological environments for epenthesis would then be, essentially, after any consonant, including any *t that was not the 3AN.CONJ suffix (example below under rubric of 9e(iii)). The *‑Vwe- and *‑aye- sequences that arose from 9e(i) evidently always underwent contraction, and the combination of *V + *‑w/*‑ẅ also always resolved to a long vowel, whether this was by compensatory lengthening, coalescence, historical contraction, or at least synchronic contraction (cf. Pentland 1999:240, 250-251; Goddard 2000:126, n. 56). Rule 9e is composed of Rules 5a, 6, 8a, and 8b (and 9a), and must precede Rule 21.

Ø → e /C[≠t, ≠N]__+pan (morphologically conditioned)

(other elements to *‑pan’s interaction with preceding morphemes are expressed formally under other rules)

- *Ø- “UNSPEC” + *nakaθ- “abandon (TA)” + *‑a· “3OBJ” + *‑w “W.FMV” *‑pan “EMPH.PAST” → ?**nakaθa·wpan → *nakaθa·pa “s/he had been abandoned, left behind” (e.g., Ojibwe naganaaban, Unami nkála·p “s/he was left” [Goddard 2021:90, ex. 4.69m])

- Cf. with preceding: *nakaθ- + *‑a· + *‑ẅ “3” + *‑pan → ?**nakaθe·wpan [with vowel umlaut before *ẅ] → *nakaθe·pa “s/he (PROX) had abandoned (s.o. (OBV))” (e.g., Unami ‡nkále·p “s/he (PROX) abandoned (s.o. (OBV))”[S19])

- Note also, showing *‑ẅ inserting preceding epenthetic *‑o- [cf. Rule 6(vii) above]: *saLakat- “be difficult (II)” + *‑ẅ + *‑pan = **saLakatẅpan → **saLakatowpan → *saLakato·pa “it had been difficult” (e.g., Ojibwe zanagadooban, Meskwaki sanakato·pani “it sure is hard”; also e.g. MalPass kələwətohpən [Sherwood 1983:232] “it was good,” with verb kələwət- “be good (II)” and /o/ from *o·)

- *we- “3” + *kya·t- “hide, conceal (TI)” + *‑aw “INAN.OBJ(CL2)” + *‑n(ay) “N.FMV” + *‑pan → **okya·tawenayepani → *okya·to·ne·pani “s/he had hidden, concealed it” (e.g., MalPass ‡hkatonehpən “s/he hid, concealed it,” Ojibwe ogaadoonaaban)

- *ke- “2” + *ne·m- “see (TI)” + *‑e· [← *‑am by Rule 27a(i)] “INAN.OBJ(CL1)” + *‑ʔm “FMV” + *‑enaw “1pl.INCL” + *‑pan → **kene·me·ʔmenawepan → *kene·me·ʔmeno·pa “we (incl.) had seen it” (e.g., Menominee kenε·memeno·pah “but we (incl.) saw it”)

- *tahkwen- “seize (TA)” + *‑at “2sg»3AN.CONJ” + *‑pan → *tahkonatepane· “if you (sg.) had seized h/” (e.g., Ojibwe dakonadiban; cf. outcome of *‑t “3AN.CONJ” + *‑pan as *‑span with no epenthesis)

- *po·si- “embark (AI)” + *‑a·nk “1pl.EXCL.CONJ” or *‑ankw “1pl.INCL.CONJ” + *‑pan → *po·siya·nkepane· “if we (excl.) had embarked” or **po·siyankwepane· → *po·siyankopane· “if we (incl.) had embarked” (e.g., Ojibwe booziyaangiban and booziyangoban ~ booziyangiban (excl. / incl.))

(10) The 3OBJ theme sign *‑a· is deleted before a vowel-initial agreement suffix in the conjunct or imperative orders. Rule 10 must precede Rules 11, 12, and 25.

a· → Ø /__+V (morphologically conditioned)

- *wa·pam- “look at (TA)” + *‑a· “3OBJ” + *‑ak “1sg»3AN.CONJ” → *wa·pamØake· “if I look at h/” (e.g., Ojibwe waabamag “if I see h/”)

- Cf., with intervening suffixes protecting the theme sign from deletion: *wa·pam- + *‑a· + *‑hsi “DIM” + *‑w “IRR” + *‑ak → *wa·pama·hsiwake· “if I don’t look at h/ even a little bit” (e.g., Ojibwe waabamaasiwag “if I don’t see h/”)

- *wa·pam- + *‑a· + *‑ehkwe “2pl»3AN.IMPER” → *wa·pamØehko “(you pl.) look at h//them!” (e.g., Meskwaki wa·pamehko, Plains Cree wāpamihk “(you pl.) see h//them!”)

(11) An epenthetic *‑y- is inserted between two vowels in several cases. These are: (i) between any two long vowels; (ii) between the vowel of the reduplicant and of the stem in reduplicated vowel-initial stems; and (iii) between a conjunct central agreement suffix beginning with a vowel other than *e, and any preceding element ending in a vowel (viz. a vowel-final AI stem or the 1OBJ theme sign *‑i). The restriction of the environment of 11(iii) to occurring with all conjunct central agreement suffixes except those beginning in *e is regrettably awkward, but is required in order to avoid a clash with Rule 21 (the contraction of *VGe sequences; see discussion there). In these cases, per Rule 12 below, the *e is subsequently lost. Rule 11 must follow Rules 3, 7, and 10, and must precede Rule 12.

Ø → y /V~__V (technically morphologically conditioned)

Ø → y /Vː__Vː

Ø → y /V+__V[≠e] (morphologically conditioned)

- *akwa·- “out of water” + *‑a·‑ʔθi “be blown by wind (AI Final)” → *akwa·ya·ʔšiwa “s/he is blown ashore” (e.g., Ojibwe agwaayaashi)

- *a·~ “REDUP [≈CONTINUATIVE]” + *a·timwi- “narrate, tell (AI)” → *a·ya·čimowa ≈“s/he narrates a long story, for a while” (e.g., Ojibwe aayaajimo, Menominee aya·cemow, Meskwaki a·ya·čimowa [Dahlstrom 1997:213]; and cf. Munsee aayə̆laachíiməw “s/he’s telling different stories; s/he’s telling stories slowly” [Goddard 2014:144] ← *a·yeθa·čimowa, reduplicated form of *eθa·čimowa “s/he narrates {thus}, tells {such} a story”)

- *api- “sit (AI)” + *‑e·kw “2pl.CONJ” + *‑i “NON3.PART” + IC → *e·piye·kwi “you (pl.) who are sitting” (e.g., MalPass epəyekw “you (du.) who are sitting”)

- Cf., with no *‑y- between the stem and ending: the consonant stem *pemihθin- “be lying down (AI)” + *‑e·kw + *‑i + IC → *pe·mihšine·kwi “you (pl.) who are lying down” (e.g., MalPass peməssinekw “you (du.) who are lying down”)

- *wa·pam- “look at (TA)” + *‑i “1OBJ” + *‑an “2sg.CONJ” + *‑e· “SBJV” → *wa·pamiyane· “if you (sg.) look at me” (e.g., Ojibwe waabamiyan “if you (sg.) see me,” Meskwaki ‡wa·pamiyane)

- Cf., with no *‑y- between the theme sign and following suffix, the consonant-initial ending *‑te· in: *wa·pam- + *‑i + *‑t “3AN.CONJ” + *‑e· → *wa·pamite· “if s/he looks at me” (e.g., Ojibwe waabamid “if s/he sees me,” Meskwaki ‡wa·pamite)

- Cf. also lack of application of Rule 11 when the central ending begins in *e: *wa·pam- + *‑i + *‑enk “UNSPEC.CONJ” + *‑e· → **wa·pamienke· → *wa·paminke· [by Rule 12] “if I’m looked at” (e.g., Meskwaki ‡wa·pamike)

(12) In a sequence of two consecutive vowels, the second is lost. Due to the operation of several previous rules, the second vowel is always short.[20] Rule 12 must follow Rules 1a, 1b, 8a, 10, 11, and possibly 8b and 8c.

V → Ø /V__

- *a·p- “untie” + *‑i “mass, weight (Prefinal)” + *‑ah‑w “by tool (TA Final)” → stem *a·pihw- “untie (TA)” (e.g., Meskwaki a·pihw-)

- *ki·šk- “sever” + *‑kw‑e·- “neck” + *‑ah‑w → stem *ki·škikwe·hw- “chop s.o.’s head off, behead (with an axe, etc.) (TA)” (e.g., Ojibwe giishkigwee’w-, Unami ki·ski·k·wehw-, Miami-Illinois kiihkikweehw- [Old Illinois kiiskikweehw-][S21])

(13a) The formative *‑ẅ “3” and a homophonous derivational suffix (and its derivatives, for which see Rule 6(iv)/6(v) above) cause a preceding *a· (either the 3OBJ theme sign *‑a· or a stem-final *a·) to undergo umlaut to *e·. In the case of the formative *‑ẅ, another morpheme may intervene. Rule 13a must precede Rules 14, 17, 18, and 21.

a· → e· /__(+X)+ẅ (morphologically conditioned)

- *pya·- “come (AI)” + *‑ẅ “3” + *‑a “PROXsg → *pye·wa “s/he comes” (e.g., Meskwaki pye·wa, Munsee péew, Menominee pi·w, Miami-Illinois piiwa)

- Cf., with no *‑ẅ to condition umlaut: *ne- “1” + *pya·- → *nepya· “I come” (e.g., Meskwaki nepya, Munsee mpá, Menominee nepya·m, Miami-Illinois nimpya)

- Note an intervening morpheme is transparent to the triggering of umlaut: *pya·- + *‑ri “MARK.OBV.SBJ” + *‑ẅ + *‑ari “OBVsg” → *pye·riwari “s/he (OBV) comes” (e.g., Meskwaki pye·niwani, Unami archaic pé·ləwal [Goddard 2021:63])

- *na·θ- “fetch (TA)” + *‑a· “3OBJ” *‑ẅ + *‑a → *na·θe·wa “s/he (PROX) fetches (s.o. (OBV))” (e.g., Menominee na·nε·w)

- Cf. *Ø- “UNSPEC” + *na·θ- + *‑a· + *‑w “W.FMV” + *‑a → *na·θa·wa “s/he is fetched, someone fetches h/” (e.g., Menominee na·na·w)

- *wetama·- “smoke a pipe (AI)” + *‑ẅ “AI⇒Initial” + *‑api “sit (AI Final)” → stem *otame·wapi- “sit smoking (AI)” (e.g., Meskwaki atame·wapi-)

(13b) Traditionally, a second umlaut pattern is reconstructed as occurring only with a single Final, *‑ya· “go, move (AI Final),” which became *‑yi· before *|ẅ|. As with the much more common *a· → *e· umlaut, another morpheme could presumably intervene before inflectional *‑ẅ. Rule 13b must precede Rules 18 and 21.

ya· → yi· /__(+X)+ẅ (morphologically conditioned)

- *eθya·- “go {somewhere} (AI)” [with Initial *eθ- “RR:GOAL”] + *‑ẅ “3” → ?*ešyi·wa “s/he goes {somewhere}” (NipAlg izhii [Jones 1977:59], Menominee esi·w)

- Cf. *eθya· + *‑t “3AN.CONJ” + *‑i “INDIC” → *ešya·či “when s/he went {somewhere}” (NipAlg izhaaj [ibid.], Menominee esya·t)

Pentland’s (1999, 2023) view on umlaut was significantly different from the general Algonquianist consensus (which I generally share); he agreed that umlaut existed, but believed that all verbs shared exactly the same umlaut patterns, and that all AI and II verb stems ending in *a· or *e· really ended in *a·, which umlauted to *e· only before *‑ẅ and a few other morphemes. He thus rejected the existence of an equivalent of Rule 13b, of AI verbs in “stable”/non-umlauting *‑a· (see e.g. Rule 17), of an umlaut of *e· to *a(·) in certain forms (see Rule 16), or of an II Final of the shape *|‑yayi| (see Rule 14(iv) and here in the section on *ayi contraction), among other things. Several of these points will be addressed in the relevant sections below.

I think his argument that Rule 13b didn’t exist (and instead *‑ya· “go, move” simply umlauted to *‑ye· per Rule 13a, and was later replaced in many daughters by the more productive AI Final *‑i· “go” [Pentland 2023, e.g. pp. 1971-1972]) is his most plausible one—despite the fact that it would bizarrely involve the three languages in which *ye· fell together with *i· by sound law (Ojibwe, Menominee, and Miami-Illinois) being precisely the languages which didn’t replace the original “go” Final in such verbs with a reflex of the Final *‑i·. But I need more time to consider this proposal before discussing it in further detail here.

(14) In a number of morphologically defined cases, the *i in a sequence *Giw is replaced by *e. Resulting *Vwe and *Vye sequences subsequently undergo contraction to a long vowel, or else a resulting postconsonantal *ye or *we coalesces to *i / *o. (The multiple *VGe contraction processes are subsumed under Rule 21, and are discussed in further detail in their own section below; coalescence of *ye and *we are covered in Rules 20a and 20b.). Specific cases in which this rule applies include when (Goddard 1991:176, 2013:108, n. 33): (i) the intransitive Final *‑iwi “be” is added to a noun stem in *‑w or *‑y; (ii) middle-reflexive AI verbs in *‑wi are inflected with a following *‑w; (iii) the verb *ni·pawi- “stand ({somewhere}) (AI)” or corresponding AI Final *‑ika·pawi “stand” are inflected with a following *‑w; (iv) the II Final *‑ye·yi (from underlying *|‑yayi| by Rule 15 below; further discussion of this Final is below) is inflected with a following *‑w; and (v) the antipassive Final *‑iwe· follows stems in *Cw. Rule 14 must follow Rules 9a and 13a, and must precede Rules 15, 18, 20a, 20b, 21, and 22.

i → e /G__{w,ẅ} (morphologically conditioned)

- *erenyiw- “man” + *‑iwi “be (AI/II Final)” + *‑ẅ “3” + *‑a “PROXsg” = **erenyiwiwiwa→ **erenyiwewiwa → *ereni·wiwa [*iwe → *i· contraction] “he is a man” (e.g. [Goddard 2006:191, n. 41]: Ojibwe ininiiwi, Arapaho hiineníínit, Cheyenne é-hetanéveo’o |=hetanéve-o| “they are men,” Moose Cree ililīwiw “he is a person, human, Cree, Native person; he is alive”)

- *nepy- “water” + *‑iwi + *‑ẅ + *‑i “INANsg” → **nepyewiwi → *nepiwiwi [*‑ye- → *‑i- coalescence] “it’s wet” (e.g., Meskwaki nepiwiwi)

- *ki·wa·mwi- “flee about (AI; middle-reflexive)” + *‑ẅ + *‑a “PROXsg” → **ki·wa·mwewa → *ki·wa·mowa “s/he flees here and there” (e.g., Meskwaki ki·wa·mowa; also e.g. Menominee me·cehsow “s/he eats” with verb |me·cehswi‑| ← PA *mi·čihswi- “eat (AI; middle-reflexive)”)

- Cf., with unmodified *i: *ki·wa·mwi- + *‑ankw “1pl.INCL.CONJ” → **ki·wa·mwiankwi → *ki·wa·mwiyankwe “that we (incl.) flee here and there” (note Menominee mi·cehsiyah “that we eat”; cf. Meskwaki [e·h‑]ki·wa·moyakwe [Thomason 2003:172] with o generalized throughout middle-reflexives)

- Note a non-middle-reflexive in *‑wi lacks this shift: *weLakwi- “be fat (AI)” [= *weLakw- “fat” + *‑i “(AI Final)”] + *‑ẅ + *‑a → *oLakwiwa “s/he’s fat” (e.g., Meskwaki anakwiwa)

- *ni·pawi- “stand ({somewhere}) (AI)” + *‑ẅ + *‑a → **ni·pawewa → *ni·po·wa “s/he stands ({somewhere})” (e.g., Cheyenne é-néé’e |=néé|; most other languages have changed the result of the contraction here to be *a· [Goddard 2000:94] or eliminated it)

- Cf. *ni·pawi- + *‑t “3AN.CONJ” → *ni·pawite· “if s/he stands ({somewhere})” (e.g., Ojibwe niibawid)

- *wa·p- “white” + *‑yayi “be, have quality (II Final)” + *‑ẅ + *‑i “INANsg” = **wa·pyayiwi → **wa·pyayewi → *wa·pya·wi “it’s white” (e.g., Oji-Cree waabaa, Sauk wa·pya·wi “it’s gray,” Arapaho stem |noočoo‑|)

- *sakipw- “bite (TA)” + *‑iwe· “ANTIP (AI Final)” → **sakipwewe·- → AI stem *sakipowe·- “bite (people)” (e.g., Meskwaki sakipowe·- [Goddard 2023:278, ex. 4.289i], Menominee |sakepowε·‑|)

(15) The sequence *‑ya- between two consonants becomes *‑ye·-. Rule 15 must follow Rules 9b and 14, and must precede Rules 16, 18, and 21.

a → e· /Cy__C

- *aʔseny- “rock, stone” + *‑ari “INANpl” and/or *‑aki “AN.PROXpl”[22] → *aʔsenye·ri ~ *aʔsenye·ki “rocks, stones” (e.g., Ojibwe asiniin ~ asiniig, Potawatomi sənyek [Lockwood 2017:97], Meskwaki asenye·ni, Shawnee [pak]aʔθenyeeki “pebbles”)

- Medial *‑epy- “water, liquid” [regular ← noun stem *nepy- “water”] + Postmedial *‑ak → Medial *‑epye·k- “water, liquid” (e.g., *akwa·- “out of water” + *‑epy‑ak- + *‑i· “move (AI Final)” → *akwa·pye·ki·- “get out of the water, come ashore (AI),” as in Meskwaki akwa·pye·ki·-)

- Irregular initial-changed form of *pya·- “come (AI)”: *pya·- + *‑t “3AN.CONJ” + *‑a “PROXsg.PART” + IC [= infixation of *‑ay‑] → **py<ay>a·ta → *pye·ya·ta “s/he who came” (e.g., Meskwaki pye·ya·ta, Munsee péeyaat, Unami pé·a·t)

- Cf., with “regular” initial change: *pa·hpi- “be playful (AI)” + *‑t + *‑a + IC → *paya·hpita “s/he who is playful” (e.g., Ojibwe bayaapid “s/he who laughs”; [with regular loss of initial change of *a·:] Meskwaki ‡pa·hpita “s/he who performs tricks,” Unami ‡pa·pi·t “s/he who plays”)

(16) Instead of the *a· to *e· umlaut of Rule 13a, several morphemes instead cause umlaut of a preceding *e· to *a or *a·. These include, among others: (i) the nominalizing suffix *‑n; (ii) the formative *‑n(ay); (iii) the archaic nominalizing suffix *‑ʔm; (iv) the suffix *‑ntay which becomes the CINA preterit;[23] (v) the transitivizers *‑θ and *‑t; and (vi) the Finals *‑s(‑w), *‑s‑w‑i “by heat(ing), burning.” See further below for these last two. Unlike the umlaut patterns covered by Rules 13a and 13b, there’s evidence that for at least some of these, an intervening morpheme does block its application. Rule 16 must follow Rule 15, possibly must precede Rule 19, and forms a component of Rule 27a.[24]

e· → a(·) /__+{n(ay),n,ʔm,ntay,θ,t,s(‑),…} (morphologically conditioned)

- *pepikwe·- [~ initial-syllable vowel *a] “play a flute (AI)” + *‑n “NMLZ” + *‑i “INANsg” → *pepikwani [~ *pa…] “flute” (e.g., Ojibwe bibigwan, Menominee pepi·kwan, Miami-Illinois papikwani “gun,” Munsee ăpíikwan “musical instrument”)

- Cf. *ne- “1” + *pepikwe·- → *nepepikwe· “I’m playing a flute” (e.g., Ojibwe nimbibigwee, Menominee nepε·pekim [← pre-Menominee *|nεpεpekwε·+m|], Miami-Illinois †nipipikwee, Munsee ntapíikwe “I play a flute, musical instrument”)

- *ne- “1” + *mi·riwe·- “give (AI(+O))” + *‑n(ay) “N.FMV” + *‑i “INANsg” → *nemi·riwa·ni “I give it (away)” (e.g., Penobscot nə̀miləwαn)

- Cf. *ne- + *mi·riwe·- → *nemi·riwe· “I give” (e.g., Penobscot nə̀miləwe)

- *wenike·- “to portage (AI)” + *‑(e)ʔm “NMLZ” → *onikaʔmi “a portage” (e.g., Ojibwe onigam)

- Cf. *ke- “2” + *wenike·- → *ko·nike· “you (sg.) portage” (e.g., Ojibwe g[id]oonigee)

- *we- “3” + *pemwehθe·- “walk along (AI)” + *‑ntay “OPT” [see footnote 23 above] → *opemohθa·nta “may s/he walk along” (e.g., older(/High?) Plains Cree opimohtāh(tay) “s/he walked along”)

- Cf., with intervening morpheme apparently blocking umlaut: *we- + *pemwehθe·- + *‑ri “MARK.OBV.SBJ” + *‑ntay → *opemohθe·rinta “may s/he (OBV) walk along” (e.g., older(/High?) Plains Cree opimohtēyih(tay) “s/he (OBV) walked along”)

Rule 16 results in the only known interconsonantal *‑ya- sequences in PA (which had been removed by Rule 15 above). When an element ending in *‑ye· is followed by a morpheme which triggers *e· → *a umlaut, the result is a surface *CyaC sequence (cf. Goddard 2001:191-192). Such triggering morphemes included (as noted above) the Finals for “heating/burning” beginning in *‑s such as TI(1) *‑s; and the causative Finals TA *‑θ, TI(2) *‑t. For example:

- *wi·ʔsak- “painful; bitter” + *‑nenty‑e·- “hand” + *‑s‑wi “by heat, burning (AI Final)” → **wi·ʔsakinentye·swi- → AI stem *wi·ʔsakinenčyaswi- “burn one’s hand” (e.g., Kickapoo iiθakinecaθo‑)

- Cf. *wi·ʔsak- + *‑nenty‑e·- + *‑hθin “lie, fall (AI Final)” → AI stem *wi·ʔsakinenčye·hšin- “hurt one’s hand” (e.g., Kickapoo iiθakineceesin‑)

- *mo·škine·- “full” + *‑epye· “by water, liquid (AI/II Final)” + *‑θ “(TA Final)” or *‑t “(TI Final)” = **mo·škine·epye·θ/t- → *mo·škine·pyaθ/t- “fill s.o./sth. up with water, liquid (TA/TI)” (e.g., Menominee mo·skenεpyaN- (TA), mo·skenεpyat‑aw- (TI))

- Cf. *mo·škine·- + *‑epye· → *mo·škine·pye·- “be full of liquid (AI/II)” (e.g., Menominee mo·skenεpi·w “s/he/it is full of liquid” = |mo·skenε·-εpy‑ε·‑| + inflectional |‑ẅ|) (Goddard 2001:192)

Of the two possible outcomes of Rule 16, *a or *a·, the former was the more archaic (Goddard 1974:326, n. 66, 2007). For example, the nominalizer *‑n sometimes conditions umlaut to *a· and other times, in nouns that had been created at an earlier period, umlaut to *a, but the homophonous verbal formative ultimately derived from it only conditions umlaut to *a·. (Meanwhile, the nominalizer *‑ʔm conditions *e· → *a umlaut, while the homophonous verbal formative derived from it doesn’t condition umlaut at all.) There were other cases as well in which what were etymologically the same morpheme, but had since become differentiated, condition different umlaut outcomes under Rule 16. For example, the Finals *‑θ (TA) / *‑t (TI) normally serve as vague, general transitivizers or applicatives, and in such use they condition umlaut to *a·, as illustrated above. In rarer cases, however, they are causatives, and in that use they condition the more archaic umlaut to *a (cf. Goddard 2023:208-209, §37.6, 297-298, §§54.11-12 [describing Meskwaki]).

- Nominalizer *‑n = *a in more archaic cases: *e·ške·- “hunt beaver under the ice (AI)” + *‑n “NMLZ” → *e·škani “ice chisel (inan.)” and *e·škana “antler, horn (anim.)” (e.g., Ojibwe eeshkee- → eeshkan, Pessamit Innu esse- /esse‑/ → eshkan /eʃkən/; noun more widely attested, e.g., Mass ⟨askon⟩ ⫽a·skan⫽ [Psa. 18:2])

- But = *a· in most later, more productive / widespread formations: *apwe·- “bake, roast (sth./s.o.) over fire (AI(+O))” + *‑n → *apwa·ni ~ *apwa·na “roasted food item, roasted meat” (e.g., Ojibwe abwee- → abwaan, Menominee |apwe·‑| → apwa·n, Arapaho hočei- → hóčoo “steak; something fried”; in many EA languages verb often lost but noun remains as “bread” (originally “roasted cornbread”): Penobscot àpαn [← verb ape‑], Western Abenaki abʌ̨n, Munsee ăpwáan, Unami ahpɔ́·n |apwān|, etc.)

- And note the following noun, with an originally archaic *a: *ti·me·- “paddle (AI)” + *‑n → *či·mani “canoe” (Arapaho noun = θííw “boat,” pl. θííwonoʔ = |θííwon| [verb lost])

- But with original archaic *a replaced by more productive umlaut to *a· in the other daughters (Goddard 1974:326, n. 66, 2015b:402, n. 39): as if from PA *či·ma·ni (e.g., Ojibwe jiimee- → jiimaan, Meskwaki či·ma·ni [verb lost], Miami-Illinois ciimee- → ciimaani “a paddle, oar” [MyPD])

- Nominalizer *‑ʔm = *a (example repeated from above): *wenike·- “to portage (AI)” + *‑ʔm “NMLZ” → *onikaʔmi “a portage” (e.g., Ojibwe onigee- → onigam)

- But formative *‑ʔm = no umlaut: *ne- “1” + *po·n- “set down, place, cease to hold (TI)” + *‑e· [← *‑am by Rule 27a(i)] “INAN.OBJ(CL1)” + *‑ʔm “FMV” + *‑ena·n “1pl.EXCL” → *nepo·ne·ʔmena· “we (excl.) set (sth.) down, (etc.)” (e.g., Menominee nepo·nε·menaw “we (excl.) put it in the pot”)

- Transitivizers *‑θ/*‑t = *a as causatives (rarer): *pi·ntwike·- “enter, go inside (AI)” + *‑θ “CAUS (TA Final)” or *‑t “CAUS (TI(2) Final)” → *pi·ntwikaθ- (TA) / *pi·ntwikat‑aw- (TI) “bring s.o. / sth. in, inside” (e.g., Ojibwe biindigee- → biindigaN-/biindigad‑oo-, Meskwaki pi·tike·- → pi·tikaN-/pi·tikat‑o·-, Menominee pi·htikε·- → pi·htikaN-/pi·htikat‑aw-)

- But = *a· as applicatives (common and productive): *a·teʔro·hke·- “tell a sacred myth (AI)” + *‑θ “APPLIC (TA Final)” → *a·teʔro·hka·θ- “tell a sacred myth about s.o. (TA)” (e.g., Ojibwe aadizookee- → aadizookaaN-, Meskwaki a·teso·hke·- → a·teso·hka·N-; cf. Unami a·thilu·he·- → a·thilu·ha·l- “tell a sacred myth to s.o. (TA)” [LTD])

(17) The sequence *aw‑w simplifies, with compensatory lengthening, to *a·w, at least in verb inflection and derivation; there are some apparent exceptions in nouns and pronouns, some perhaps representing later analogy by the daughters, and/or perhaps what were not actual *aw‑w sequences at a pre-PA stage. Because it follows the application of umlaut, Rule 17 creates a class of verb stems (all AIs) with “stable” or non-umlauting *a·, which does not shift to *e· or *i· before *‑ẅ. Such verbs originally would have had stem-final *‑a· only in certain inflections, but by the PA period the vowel had been analogically extended to all contexts. Rule 17 must follow Rules 6, 9b, and 13a, must precede Rules 18, 19, 20b, and 21, and forms a component of Rule 27b.

aw → a· /__+w

- *maw- “weep, cry (AI)” + *‑ẅ “3” + *‑a “PROXsg” = **mawwa → *ma·wa “s/he weeps” (e.g., Menominee ma·w, Mass ⟨mâu⟩ ⫽mʌ̨·w⫽)

- Cf. *maw- + *‑rwe “2sg.IMPER” → *mawero “(you sg.) weep!” (e.g., Menominee mo·non [= |maw-ε-non| with vowel contraction], Mass ⟨maush⟩ ⫽mawəš⫽)

- Verbs in stable *a· were for the most part originally the middle-reflexives (formed by the suffix *‑w) of transitive stems in *‑aw, which were often benefactives or other ditransitive verbs (Goddard 1974:326, n. 60, 1979b:65-66), e.g.: *aθoskye·- “work” + *‑ʔta· “act, do (AI Final)” = stem *aθoskye·ʔta·‑, + *‑ẅ + *‑a → *aθoskye·ʔta·wa “s/he is engaged in work, does work” (e.g., Menominee anohki·ʔtaw)

- Cf. the corresponding benefactive TA in *‑aw (with the above verb’s stem originating in *‑aw + middle-reflexive *‑w): *aθoskye·- + *‑ʔtaw “act, do for, in relation to (TA Final)” = stem *aθoskye·ʔtaw-, + *‑a· “3OBJ” + *‑ẅ + *‑a → *aθoskye·ʔtawe·wa “s/he (PROX) works for (s.o. (OBV))” (e.g., Menominee anohki·ʔtawεw)

- The effects of Rule 17 could also be seen in the allomorphy of the TI(2) theme sign; for discussion and an example, see Rule 27b(ii) below.

- But cf, with no operation of Rule 17 (and simplification of *ww to *w by Rule 18 instead): *ke- “2” + *‑i·raw- “(emphatic personal pronoun base)” + *‑wa·w “2pl/3pl” → **ki·rawwa·w → *ki·rawa· “you yourselves, as for you (pl.)” (e.g., Ojibwe giinawaa, Shawnee kiilawa, Woods Cree kīthawāw [Starks 1992:49])

(18) The second of two consecutive semivowels drops. (Pentland 1999:248-249 claims that—at least in inflection—it’s the first semivowel that drops, but his apparent reasons can be explained in other ways.) Rule 18 must follow Rules 6, 9b, 9c(=9a), 9d(=9a), 13a, 13b, 14, 15, and 17, and must precede Rules 19, 20a, 20b, 21, and 22.

G → Ø /G__

- *ke- “2” + *koʔθ- “fear (TA)” + *‑a· “3OBJ” + *‑w “FMV” + *‑wa·w “2pl/3pl” + *‑aki “PROXpl” → **kekoʔθa·wwa·waki → *kekoʔθa·wa·waki “you (pl.) are afraid of them” (e.g., Moose Cree kikoštāwāwak)

- *ne- “1” + ?*paspakam- “hit repeatedly (TA)” + *‑ekw “INV” + *‑w + *‑ena·n “1pl.EXCL” + *‑a “PROXsg” → **nepaspakamekwwena·na → **nepaspakamekwena·na → ?*nepaspakamekona·na [*we → *o by Rule 20b] “s/he hit us (excl.) repeatedly” (e.g., Unami ‡mpəpahkámkwəna)

- Cf., with intervening suffix preventing loss of the second *w: *ne- + ?*paspakam- + *‑ekw + *‑hsi “DIM”+ *‑w + *‑ena·n + *‑a → **nepaspakamekwhsiwena·na → ?*nepaspakamekohsiwena·na “the little one (anim.) hit us (excl.) repeatedly” (e.g., Unami mpəpahkamkwət·í·wəna)

- *taskw- “short” + *‑yayi “be, have quality (II Final)” + *‑ẅ “3” + *‑i “INANsg” → **taskwyayiwi → *taskwa·wi “it’s short” (e.g., Ojibwe dakwaa)

(19) The sequence *wa between consonants in nominal and verbal inflection usually coalesces to *o·, but there are certain exceptions. The pattern in nominal inflection (Goddard 1981a:280-283, esp. 282, 2001:177, 182) was apparently that coalescence occurred: (i) always in inanimate nouns; (ii) always in animate stems ending in a consonant other than the sequence *‑kw; (iii) almost never (perhaps never) in names for animals ending in *‑kw; and (iv) sometimes, but more often not, in other animate stems ending in *‑kw. In verbal inflection, coalescence occurs when a disyllabic peripheral suffix beginning in *a (probably the only possibilities are *‑aki “AN.PROXpl” or *‑ari “INANpl”) is preceded by one of the formatives *‑w or *‑ẅ when these follow a consonant, viz. principally after: (v) the inverse theme sign *‑ekw; (vi) the TI(1) theme sign *‑am; and (vii) an II, AI, or TI(3) stem in *‑C. (Possibly only certain consonants led to coalescence by 19(vii).) Otherwise, coalescence in verb inflection does not occur, such as (viii) with an *a-initial conjunct central agreement suffix following a verb stem in *‑Cw (cf. Pentland 1999:249).

The degree to which *CwaC was retained as such in derivation isn’t entirely clear, but (ix) there are certainly a number of instances where it does coalesce, and this was the older treatment in most phonological environments. Because PA *CwaC is not reconstructible morpheme-internally except when the first consonant is *k (Nilsen 2017:20 citing Goddard, p.c.; cf. Pentland 2023), it’s quite likely that *wa-coalescence was originally a simple pre-PA sound change which was only blocked when the “*w” was really part of a pre-PA unit phoneme *kw (contrasting with a cluster *kw), following Pentland’s (1999:226; cf. also Goddard 2001:182, n. 34) implicit suggestion. There is also comparative Algic evidence to support part, though not all, of this. As Goddard notes, however, and as the environments detailed in the previous paragraph make clear, the patterns which resulted from this sound change had become morphologized and disrupted by analogy by the actual Proto-Algonquian period. Rule 19 must follow Rules 6, 9b, 9d(=9a), 17, 18, and possibly 16.

wa → o· /C__C (lexically / morphologically conditioned)

- Inanimate noun — shows coalescence:

- *meʔtekw- “stick; tree” + *‑ari “INANpl” → *meʔteko·ri “sticks; trees” (e.g., Ojibwe mitigoon “sticks,” Meskwaki mehteko·ni, Arapaho bêeteíí “bows”)

- Animate noun stem not ending in *‑kw — shows coalescence:

- *we- “3” + *‑i·θemw- “cross-sibling-in-law” + *‑ahi “AN.OBVpl” → *wi·θemo·hi “h/ cross-siblings-in-law” (e.g., Northwestern Ojibwe wiinimoo’, Munsee dialectal wíiləmool [Goddard 2010:19])

- Animal name ending in *‑kw — lacks coalescence:

- *atehkw- “deer, cervid (?)” + *‑aki “AN.PROXpl” → *atehkwaki “deer (pl.), cervids” (e.g., Ojibwe adikwag “caribou (Rangifer tarandus) (pl.),” Munsee ătóhwak “deer (pl.)”)

- Non-animal animate stem ending in *‑kw — sometimes shows coalescence:

- *askehkw- “kettle [anim.]” + *‑aki “AN.PROXpl” → *askehko·ki “kettles” (e.g., Ojibwe akikoog, Meskwaki ahkohko·ki “kettles, drums,” Shawnee haʔkoʔkooki, Menominee ahkε·hkok)

- Non-animal animate stem ending in *‑kw — but usually lacks coalescence:

- *aθa(·)nkw- “star [anim.]” + *‑aki “AN.PROXpl” → *aθa(·)nkwaki “stars” (e.g., Meskwaki ana·kwaki, Shawnee halaakwaki, Unami alánkɔk |alankwak|, Old Algonquin ⟨[aran]gȣak⟩ arankwak [Aubin 2001:2])

- Verb inflection with *‑w/*‑ẅ and appropriate peripheral suffix — shows coalescence when preceded by *‑ekw “INV,” TI(1) theme sign *‑am, or *C-final II, AI, or TI(3) stem: