The Red River of the North is born south of Fargo-Moorhead on the Minnesota-North Dakota border and flows north for 550 miles, passing through Winnipeg, before emptying into Lake Winnipeg. Its banks and watershed have been of great historical importance—a history in which Ojibwe-speaking peoples have played a pivotal role. The Red River country was the site of long-term fur trading and a particularly rich mixture of peoples and cultures—Crees and Anishinaabeg, Assiniboines, Frenchmen and Scots, and more. This mixture created some friction, but also promoted various alliances, and it was a huge factor in giving birth to the Métis people. This was the site of the Selkirk Colony and Pembina; it was the arena of the Pemmican War and the first Métis uprising under Louis Riel and the creation of Manitoba. Anishinaabeg, from Minnesota Ojibwes to Lake Huron Odawas, sojourned or settled here as they gradually pushed onto the Plains and became today’s Saulteaux (or Plains Ojibwes).

For all its significance, I’m unaware of any commonly shared Ojibwe term for the broader Red River country, but in this post I’d like to briefly delve into the closest thing that I’ve found.

The most common names for the Red River itself are Misko-Ziibi or Miskwaagamiiwi-Ziibi, which both just mean “Red River” (the latter is, a bit more literally, “river of red-colored water,” and cognate with the common Cree name of Mihkwākamīwi-Sīpiy). But the linguist Albert Gatschet once recorded a different Ojibwe name from the Pembina-Turtle Mountain Ojibwe lawyer Jean Bottineau in 1878.

Bottineau’s name for the Red River, as recorded by Gatschet, was ⟨mistawáya=usíbí⟩ (Gatschet 1878:31). This clearly breaks down as some initial element ⟨mistawáya⟩ followed by the word for “river,” ziibi (⟨síbí⟩). They’re separated by a sequence -wi-, spelled ⟨u⟩ by Gatschet, which is used in certain cases to link elements like this when creating compound words. The question, then, is what is the element represented by ⟨mistawáya⟩? As it turns out, Bottineau gives us our first clue, because he provided the gloss “British River” for this name, indicating that the ⟨mistawáya⟩ portion meant something roughly equivalent to “British,” i.e. “Canadian,” or perhaps specifically British Canadian.

A word equivalent to this “mistawáya” occurs in several other sources.

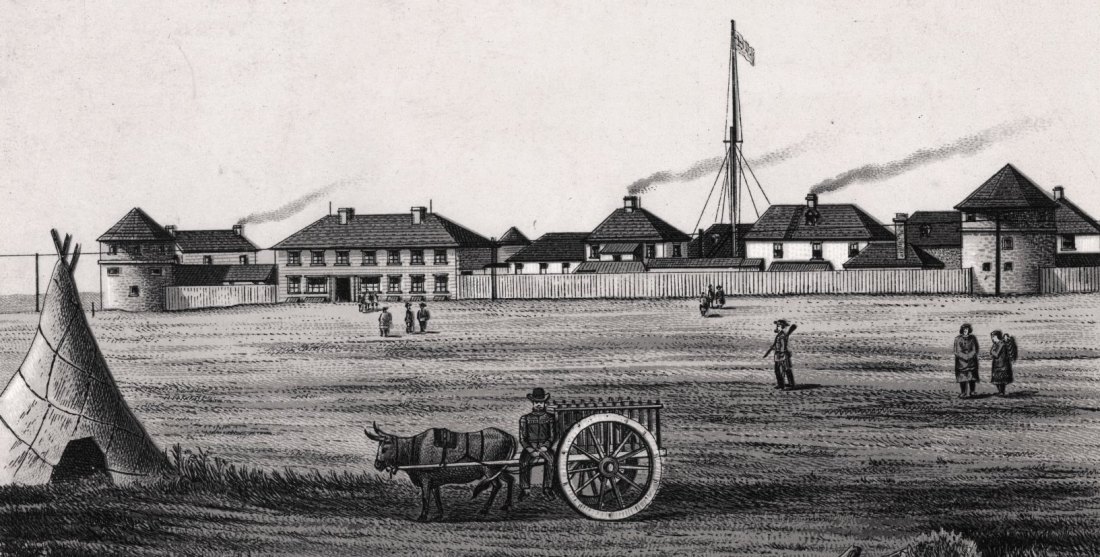

First, it occurs in another set of fieldnotes by Gatschet, which he obtained from Ignatius Tomazin, a Slovenian priest serving at the time at Red Lake, Minnesota.[1] Here, Gatschet (1883:179, 180) lists the name for the “British [i.e. Canadian] Odj. [Ojibwes] to the N. & NE. [sic]” (an error for “N & NW”?) as ⟨Mishtawáyawininiwak⟩, and a locative term “at Fort Garry” as ⟨Mishtáwayank⟩. These words break down as the “mis(h)tawaya” element plus -w-ininiwag “men/people (of)” and the locative suffix -ng, respectively. There were basically two historical Fort Garry’s, Upper Fort Garry and Lower Fort Garry, but the one no doubt intended here was Upper Fort Garry, located in what is now Winnipeg overlooking the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers (“The Forks”).

The “mis(h)tawaya” element is also found in the notes of the missionary Sela Wright, who also worked mainly at Red Lake. His Ojibwe language materials, compiled in the late 1800s, include, as the name for “Lake Winnipeg,” ⟨Mĭc-ti-wai-ang⟩ (Wright n.d.:186; the character ⟨c⟩ here represents the English “sh” sound, IPA [ʃ]), which is the same word Gatschet got from Tomazin in the meaning “at Fort Garry”—i.e., the locative of the “mis(h)tawaya” name.

Finally, the anthropologist Alanson Skinner, working with members of Long Plain First Nation in 1913, obtained a list of historical eastern Saulteaux bands, “each one of which derived its name from the locality which it inhabited.” The first band listed is ⟨Mistowaiau-wininiwûk⟩, which Skinner translates as “Winnipeg men” (Skinner 1916:481). This is the same word Gatschet got from Tomazin in the meaning “[Canadian] Ojibwes to the north and [northwest (?)]”—i.e., the “mis(h)tawaya” name plus -w-ininiwag “men/people (of).”

Although by the late 1800s-early 1900s different Ojibwe-speaking groups used it to mean somewhat different things, the original significance of the “mis(h)tawaya” name now seems clear. The most specific meaning anyone assigns to it is Tomazin’s equation of it with (Upper) Fort Garry. The rest of the glosses follow naturally enough: from originally referring to Fort Garry, it expanded to refer to the settlement that arose around the fort and became the city of Winnipeg; other speakers used the name of the fort to name the key river which it overlooked (“Red River” being literally “Fort Garry River”); then this in turn was used to name the key regional lake into which that river drained; and then it was finally expanded, by some American Ojibwes, to refer to—at least roughly?—the Red River region of Canada, and as a designation of the Anishinaabeg who lived in that region. (The exact scope of reference isn’t possible to recover from the sources examined here.) Thus:

- “Upper Fort Garry” = reflected in Tomazin’s ⟨Mishtáwayank⟩ “at Fort Garry”; name attested from Red Lake, Minn.

- “city of Winnipeg” = reflected in Skinner’s ⟨Mistowaiau-wininiwûk⟩ “Winnipeg men” Saulteaux band; name from Long Plain Reserve #6 near Portage la Prairie

- “Red River of the North” = Bottineau’s ⟨mistawáya=usíbí⟩; name likely from Red Lake and Lake of the Woods (and Pembina?)[2]

- “Lake Winnipeg” = reflected in Wright’s ⟨Mĭc-ti-wai-ang⟩ “Lake Winnipeg”; name from Red Lake

- (?)“Red River country” (or / also something like “Canada”??) = reflected in Tomazin’s ⟨Mishtawáyawininiwak⟩ “British Odj. to the N. & NE. [sic]”[3] (name from Red Lake), and Bottineau’s gloss of ⟨mistawáya=usíbí⟩ as “British River” (name likely from Red Lake and Lake of the Woods [and Pembina?])

The knowledge that this name originally referred to Fort Garry helps solve what it represents. From its shape it must have originally been a borrowing from Cree—Ojibwe doesn’t have native words with the clusters st or sht—and specifically a word that began with mišt- “big.”[4] Wright wrote the first “a” of “mis(h)tawaya” as ⟨i⟩, while Skinner perceived it as an [o]-like sound before /w/, both of which support reconstructing it as short. The locative ending being -ng proves that the third “a” was long, but it would be impossible for it to be short in a noun of four syllables in any case. We’re thus dealing with an Ojibwe word of the shape mishtawa(a)yaa ~ mistawa(a)yaa, borrowed from a Cree word meaning “big [something]” and connected in some way to Fort Garry.

And there is a word that fits these criteria wonderfully, both in sound and meaning: mištahi-wāskāhikan “big house.” “Big house” was a common Cree and Ojibwe way to refer to whatever the local European fort was.[5] While at first glance this might not look hugely promising, the only major assumption required would be that the Cree word was shortened by the loss of its last few syllables (mištahi-wā[skāhikan]), either as some sort of hypocorism or else in the loaning process. Then the only other necessary assumptions would be that Ojibwe loaned the Cree sequence -ahi- as -ay-, which would be very reasonable, and that the -y- and -w- then metathesized (that is, switched places). In other words, the evolution of the word was Cree mištahi-wā[… → Ojibwe *mishtayawaa → mishtawayaa ~ mistawayaa.

We can thus reconstruct the following names (the use of st vs. sht is not significant):

- Mishtawayaa = “Upper Fort Garry”

- Mishtawayaang = “at Upper Fort Garry”; “[Lake] Winnipeg”; “city of Winnipeg”; “Winnipeg region ≈ the Red River Settlement”(?)

- Mishtawayaawininiwag, Mistawayaawininiwag = “Winnipeggers”(?); “Canadians”(?); “≈ Ojibwes in the Red River Settlement and general region”(?)

- Mistawayaawi-Ziibi = “Red River of the North”

Although most of these names can be traced back to speakers from the Red Lake band in Minnesota, and related bands to their north around Lake of the Woods (and perhaps to their west at Pembina), I think this is just, basically, a sampling artefact. There is more extensive high-quality 19th-century material available from the Red Lake dialect, and from America in general, than from the relevant areas of Canada. (Except for Christian works, grammars, and the like, which are less likely to have the kind of vocabulary we’re looking for than a dictionary, set of lessons, or linguistic or anthropological fieldwork.) And then there’s the fact that Skinner did find a derivative of this term in the 20th century at Long Plain Reserve #6, which is located just west of Portage la Prairie. Red Lake and Lake of the Woods were part of a deep network of familial and economic/trading ties to the Red River Settlement; their shared term with one found at Portage la Prairie leads me to suspect that this was not just coined at Red Lake, but rather was once quite widespread. Indeed, the meaning “big house” implies that it was coined in or around Fort Garry / Winnipeg itself! It’s only some of the later evolved meanings that may be particular to specific communities.

Since I’ve hardly done a comprehensive search, I don’t know whether there are further attestations of these terms, and I also don’t know if any of them are still used by any speakers today—though they are evidently obscure enough that Roger Roulette, John Nichols, and Patricia Albers (and presumably Ives Goddard) were unable to decipher Skinner’s ⟨Mistowaiau-wininiwûk⟩ (Albers 2001:653). I’m not aware that any are still used at Red Lake; for example, the modern Red Lake name for the Red River is Misko-Ziibi (Treuer 2015:366). And Winnipeg goes by several common names in different areas, but none of them are related to the terms considered here.[6]

But I could be wrong about some of this. If anyone has any additional information they can add to this picture, or any corrections, I’d love to know!

Sources Used

(“HNAI” = Handbook of North American Indians, series ed. William C. Sturtevant)

- Albers, Patricia C. (2001). “Plains Ojibwa.” In Plains, ed. Raymond J. DeMallie, pp. 652-660. HNAI vol. 13. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Anderson, Kristy, Cheyenne Ironman, Andrea Kolbe, and Wendy Ross, eds. (2020). Anishinaabemowin Climate Change Glossary. Centre for Indigenous Environmental Resources. Accessed February 15, 2024.

- Beardy, Flora, and Robert Coutts, eds. (2017). Voices from Hudson Bay: Cree Stories from York Factory. 2nd edition. Rupert’s Land Record Society Series, vol. 5. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- FOD = Weshki-ayaad [= Svetlana Pedčenko], Charles Lippert, and Guy T. Gambill (2022). Freelang Ojibwe Dictionary. Computer program, version of January 1, 2022.

- Gatschet, Albert S. (1878). [Shawnee, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi vocabularies and texts, mainly collected 1878–1879, and miscellaneous notes on Narragansett and Natchez. Includes Ojibwe material given by Jean (John) B. Bottineau, May 28, 1878, pp. 23-65, mostly odd pages only.] Manuscript 68, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

- Gatschet, Albert S. (1883). [Vocabularies and other linguistic notes on numerous languages, assembled from various sources over period of ca. 1881-1886. Includes Ojibwe vocabulary obtained from Fr. Ignatius Tomazin, January 31, 1883, pp. 178-180.] Manuscript 1449, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

- Gatschet, Albert S. (1889). [Ojibwe vocabulary and text given by Kashpash (aka Kaishpa), Washington, D.C., March 1889, as well as contributions by Joseph Rolette and Maxime Marion. Also includes newspaper clipping from January 1899.] Manuscript 1585, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

- Itwêwina = Arppe, Antti, Eddie Antonio Santos, Matt Yan, Atticus Harrigan, Katherine Schmirler, Kwabema Amoh, and Arok Wolvengrey, eds. (2019–). Itwêwina: Plains Cree Intelligent Dictionary. Alberta Language Technology Lab, University of Alberta. Accessed February 17, 2024.

- MGNP = Manitoba Geographical Names Program (2000). Geographical Names of Manitoba. Winnipeg: Manitoba Conservation.

- OPD = Nichols, John D., and Nora Livesay, eds. (2012–). Ojibwe People’s Dictionary. Department of American Indian Studies, University of Minnesota. Accessed February 13, 2024.

- Peers, Laura (1994). The Ojibwa of Western Canada, 1780 to 1870. Manitoba Studies in Native History 8. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press.

- Pentland, David H. (1978). “A Historical Overview of Cree Dialects.” In Papers of the Ninth Algonquian Conference, ed. William Cowan, pp. 104-126. Ottawa: Carleton University.

- Pentland, David H. (1979). Algonquian Historical Phonology. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Toronto.

- Skinner, Alanson (1916 [1914]). “Political and Ceremonial Organization of the Plains-Ojibway.” In Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History. Vol. XI: Societies of the Plains Indians, ed. Clark Wissler, pp. 475-511. New York: American Museum of Natural History.

- Treuer, Anton (2015). Warrior Nation: A History of the Red Lake Ojibwe. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press.

- WOD = Valentine, J. Randolph, and Patricia M. Ningewance Nadeau, eds. (2023). Western Ojibwe Dictionary. Computer program, version of January 23, 2023.

- Wright, Rev. Sela G. (n.d.) [ca. 1890]. Sela G. Wrights’s Lexical Collection for Ojibwe (Red Lake, MN). Sela G. Wright Digital Collection, Oberlin College Archives. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- Obviously it’s . . . less than ideal . . . to be relying for data on an non-native speaker informant like Tomazin, with no contemporary check on whether his translations, pronunciation, and so on were even reasonably accurate. (What cross-checking is possible would indicate that his translations do seem to be accurate.) That said, it’s important to consult all available sources; it should just always be kept in mind what each source is. ↑

- Without getting too far into the weeds on this, Jean Bottineau spoke, basically, Red Lake-Lake of the Woods Ojibwe; like many other Pembina Ojibwes, many of his ancestors were from that area. While this would not preclude him adopting placenames from speakers of other dialects, there is some evidence that in this instance he did not. Gatschet also took down a vocabulary and texts from a Turtle Mountain Ojibwe-Métis, Kaishpa, and Kaishpa’s usage does not match Bottineau’s. Instead of reflecting an original name for Fort Garry being this “mas(h)tawaya” word, Kaishpa provided ⟨Winibig⟩ for “Fort Garry” (Gatschet 1889:18), which represents Wiinibiig, a name for Winnipeg. (For more on this name, see footnote six below.) Bottineau’s usage could still reflect common Pembina usage, though, and not merely Red Lake and/or Lake of the Woods usage.

Kaishpa’s usage of Wiinibiig to refer to Fort Garry reflects the fact that for most of his life the name for the fort and the name for the city would have been practically interchangeable, with little existing outside the fort itself. In fact, one of the town’s common English names remained “Fort Garry” into the 1870s, not long before Kaishpa provided his vocabulary to Gatschet (MGNP 2000:84, 299). ↑

- As indicated a few times, I’m presuming that “NE.” is an error for “NW.”, either by Tomazin or by Gatschet. ↑

- This is now very often pronounced mist- (and is phonemically /mist-/, with no distinctive š sound) in the more western dialects of Cree, including Plains Cree, which was the source of the loan. But at the time it was borrowed into Ojibwe it would still have been pronounced varyingly as mišt- ~ mist- in Plains Cree, with the mišt- pronunciation much more common than today (cf. Pentland 1978:110-111, 114-115, 1979:85-86). For simplicity I cite it as just mišt-. ↑

- My thanks to Jennifer S. H. Brown (p.c.) for pointing this out to me; note, for example, the local Swampy Cree name for York Factory, Kihci-Wāskāhikan “Great House” (Beardy and Coutts 2017:xi, 131, n. 24). The word for “house” itself—Ojibwe waakaa’igan, Cree wāskāhikan or wāskahikan—was in fact originally a word for European trading posts, stockades, and forts, which came to apply as well to European-style houses (as opposed to Native-style lodges). Etymologically it derives from the root meaning “encircle; around” (Proto-Algonquian *wa·ska·-) and meant something like “what is built to fence things in” (in Ojibwe: waakaa- “encircle” + -a’ “perform action by tool” + -ige “action applied to unspecified object(s)” + finally an -n which turns verbs into nouns).

Note also the common use in English during the fur trade period of “house” (< “trading house”) to mean “trading post / fort”—regardless of size, etc.—and thus the great number of posts named “[whatever] House”: Brandon House, Cumberland House, Henley House, Nelson House, Norway House, Osnaburgh House, Oxford House, Rocky Mountain House, and on and on. This may at least in part account for the semantic development of “fort” > “house” in Cree and Ojibwe? ↑

- Common names for Winnipeg include Gaa-(Gichi-)Okoteg, Gaa-Okosing, Wiinibiigong, and Miskwaagamiiwi-Ziibiing. The first two names mean “Where There Is a (Big) Pile/Heap.” My guess is this is a reference to Garbage Hill? The last name just means “On the Red River” or “Red River Place.”

Wiinibiigong means “Dirty Water Place”; it’s essentially a calque of English and French in naming the city after the lake, which is called Wīnipēk “Muddy/Dirty Water” in Cree and cognate Wiinibiig in Ojibwe. As might be guessed, the English/French name for the lake is a loan from Cree. ↑